Thomas Cole and Frederick Church, founders of the American art movement known as the Hudson River School, painted large landscapes that featured mountains, steams and forests of the Hudson River Valley in the mid-19th century. Cole in particular was concerned about the encroaching industrialization of the country and the destruction of the natural environment. He used his paintings as a vehicle for education and awareness.

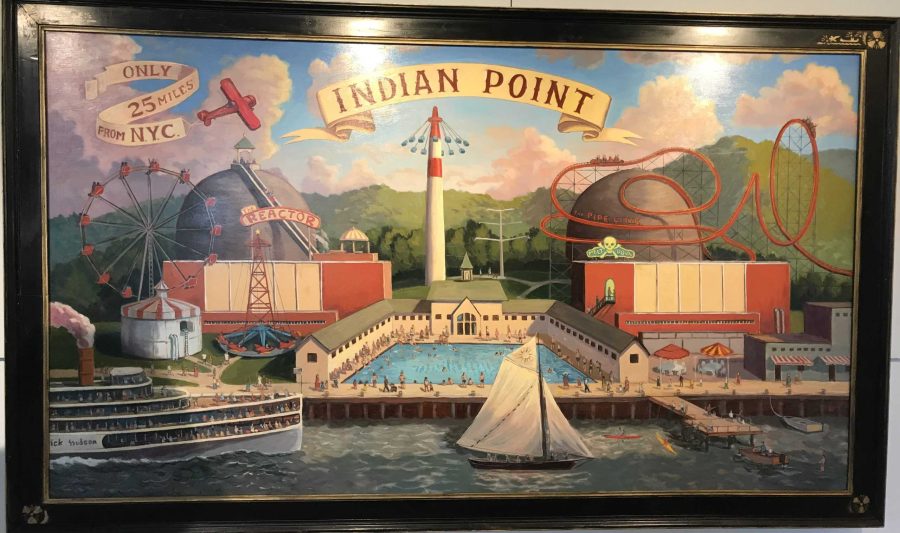

Peekskill resident and artist Andrew Barthelmes, 45, has done the same thing two centuries later with his oil on wood painting, Indian Summer.  The image measures a massive 104” by 62” inches and is a commentary on the looming closing of the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant in the spring of 2020 and 2021.

The image measures a massive 104” by 62” inches and is a commentary on the looming closing of the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant in the spring of 2020 and 2021.

Like Cole and Church who used their paintings to speak to the dreams and anxieties of the fledgling country, Barthelmes’ painting evokes the anxieties and fears connected to the closing of the Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant. He illustrates the location’s history as an amusement park with the present reality of an aging nuclear power plant facing an uncertain future. All those elements collide into an epic painting that starts conversations.

“I like to paint the people and places that are right in front of all of us, but are not seen, or noticed. I want you to really look at those things, spend some time thinking about them and hopefully make you see them in a different way. Indian Point is a perfect example of that. The domes of Indian Point are usually just barely hidden behind the trees as we admire the incredible beauty of our riverfront. But we all know it’s there,” said Barthelmes who grew up in Peekskill.

Indian Summer juxtaposes the danger inherent in the nuclear power plant with the whimsical, happy thoughts associated with an amusement park besides the river. “I wanted to mix our fears with our enjoyment, make a place that is both scary and fun by mixing the past, present and future of this one place,” said Barthelmes, 45.

Barthelmes proposed the idea of the painting with a sketch for a show at the Dorsky Museum of Art in New Paltz in 2017. The piece was accepted, and he said he worked round-the-clock to complete it for the opening of the show. “I brought it up there with the paint still drying,” he said.

One of the best parts of participating in that show said Barthelmes was standing besides the painting while people came upon it. They didn’t know he was the painter and he got to watch people’s reactions and hear their comments which was a positive experience for him since he wasn’t sure how people would respond to it. “I think viewers don’t know quite what to feel when they first view the painting. But generally, I have seen smiles, or even laughter by those that have seen it for the first time, which has been nice to see.” Those were the perfect responses, he said, because he spent a month full-time working on it alone in the South Street studio he shares with his father Bob Barthelmes and he wasn’t sure how it would go over with the public.

When the show in New Paltz closed, he wondered where the painting could go to be a public conversation starter and he reached out to environmental groups such as Riverkeeper and Clearwater. Riverkeeper said they were interested in it, so it hung on the walls of their offices in Ossining for two years before it found its way back to Peekskill. Barthelmes said he’d like to sell it and agreed to have an auction with the proceeds going to support the work of Riverkeeper.

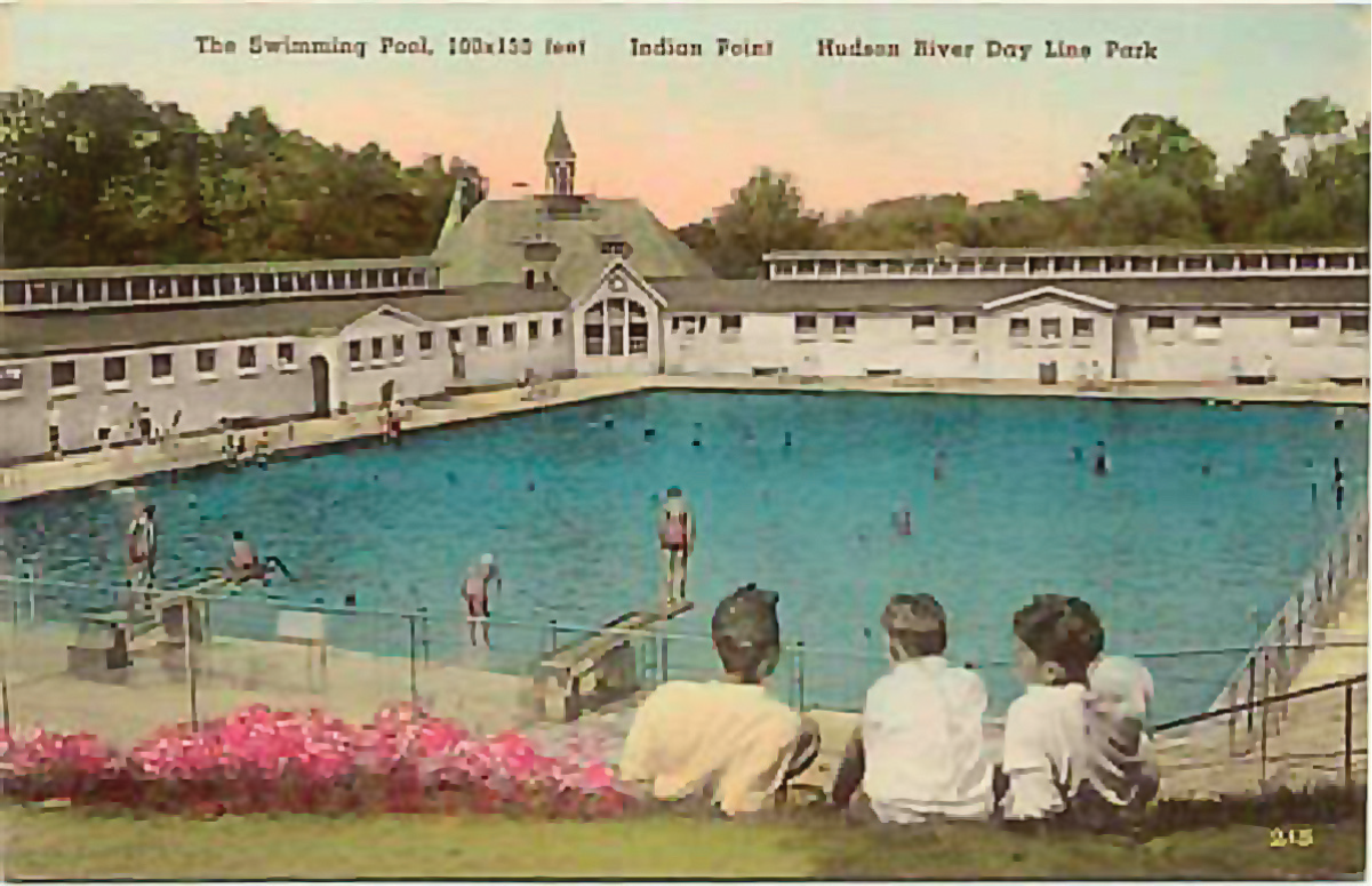

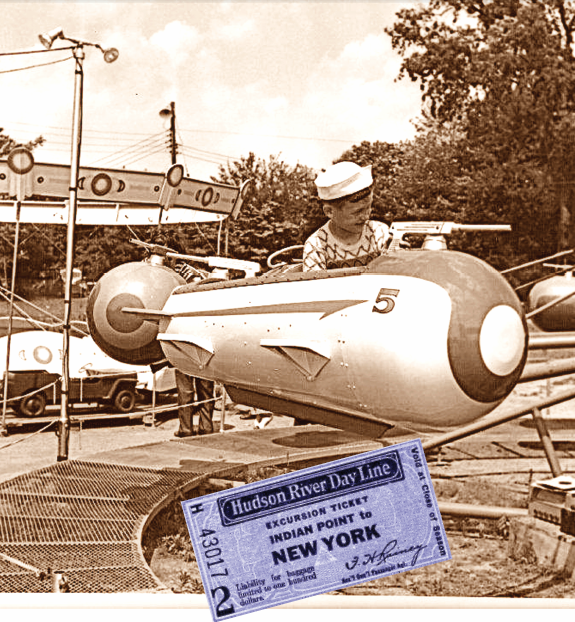

Examining the painting closely one sees all sorts of references to what Indian Point is and once was. The amusement park was owned by the Hudson River Day Line that brought people from New York up the Hudson on their steamboats. They could increase revenue if they owned a location where people could disembark. In 1923 they bought 320 acres of a former brickyard on the banks of the Hudson in Buchanan and because the Kichawank tribe once lived there, they named the park Indian Point. It had beautiful wooded paths, much like New York’s Central Park, good for picnicking and strolling. There was a beach with a small bathing area, ball fields and a dance pavilion along with terraced lawns. Six years later the company built a swimming pool, measuring 100 by 150 feet with 1500 lockers in a bathhouse.

By 1948 people were using cars to leave the city and the company fell on hard times. The park closed that year but reopened two years later under different ownership and that’s when amusement park rides were added.

By 1952 there were over 50 concessions, five ballfields, ice skating rink, outdoor arena, miniature golf and rides. The park closed in 1956 and Con Edison bought the land for $250,000 to build the power plant for New York City’s growing energy needs.

The sections of the painting where the past collides with the present center around the swimming pool. If one looks closely one sees squiggly lines that could be waves in the  water or are they the spent fuel rods that are submerged in water?

water or are they the spent fuel rods that are submerged in water?  Another area that sparks consideration is the plane that advertises how far away New York City is, The trailer on the plane says the distance to the city is only 25 miles. That’s the distance as the crow flies which is the same way radiation travels. “It can be a good thing that it’s only 25 miles from the city for a trip to an amusement park or it cannot be a good thing if you’re in the path of radiation,” said Barthelmes.

Another area that sparks consideration is the plane that advertises how far away New York City is, The trailer on the plane says the distance to the city is only 25 miles. That’s the distance as the crow flies which is the same way radiation travels. “It can be a good thing that it’s only 25 miles from the city for a trip to an amusement park or it cannot be a good thing if you’re in the path of radiation,” said Barthelmes.

In an acknowledgment to the way people travelled to Indian Point in the past, the painting shows a steamboat off to the edge of the painting. That is also a salute to the future, connecting to the work that is continuing on restoring the original SS Columbia, a 1902 steamboat. The plan is for the steamboat to run excursions up and down the Hudson again.

To learn more about the painting and details of the auction, contact Barthelmes at his Facebook page.

Painter challenges viewer to see differently

November 14, 2019

More to Discover