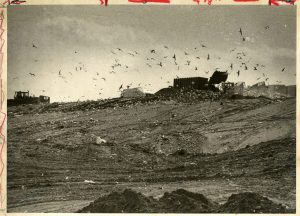

It was 1974, and newly-elected Westchester County Executive Al DelBello had inherited a heap of trouble. Specifically, the county-operated Croton Point Dump, a massive landfill on a 500-acre peninsula that juts into the Hudson from northern Westchester County, pointing south towards New York City, some thirty miles down the river.

The dump had been the final resting place for much of the county’s waste – everything from household waste to industrial toxins – since 1927. The landfill had operated alongside Croton Point Park, growing steadily as it took on the detritus of more and more Westchester communities. In 1971, a story emerged about a veterinarian humanely destroying a horse at the dump – in view of nearby picnickers – then burying it with trash, causing public outrage.

The following January, nearly a hundred Croton residents blocked bulldozers attempting to remove soil from the park to use as cover in the landfill. A group of local conservationists and leaders from Croton and nearby Cortlandt wrote to Whitney North Seymour, Jr. – the US Attorney for the Southern District of NY – asking if the landfill might be violating federal laws by allowing seepage into the Hudson.

By late spring of 1972, in an action unprecedented at the time, the federal government had sued Westchester County, charging County Executive Edwin Michaelian with allowing major pollution of the Hudson River. A 1972 New York Times article quoted US Attorney Whitney North Seymour Jr.: “Nearly 100 acres of valuable tidal marshes and streams have been destroyed. Unless immediate steps are taken, continued use and expansion of the dump will damage parklands at Croton Point and do further harm to the river.”

The federal court ordered the county to take immediate mitigating actions: double the amount of cover soil being used to bury debris; stop accepting industrial liquid waste; clean the tidal marshes; and design a dike system to contain leachate that had been seeping into the Hudson for decades. The county was in a quandary: 34 Westchester municipalities were using Croton Point to bury their solid waste; none of them were likely to be willing to host a new landfill in their mostly upscale bedroom communities. At the court’s urging, county leaders began investigating new technologies in waste disposal.

A Unique Cooperative Venture

In May 1974, DelBello, along with the state’s Environmental Facilities Corporation, presented what they called “a unique cooperative venture” that would see the county taking responsibility for the disposal of all 900,000 annual tons of its municipal waste. The plan was to phase out the nearly 50-year-old Croton Point Dump; take over and upgrade five regional incinerators that had been condemned for creating air pollution; and construct a new state-of-the-art incinerator on the Grasslands campus in Valhalla, which would provide heating, cooling, and electricity for the hospital, medical school and prison located there.

In 1976, following further study by engineering consultants, the Westchester plan was updated, replacing the idea of upgrading incinerators with the building of a second waste treatment plant – both new facilities would use an oxygen-free, high-temperature process called pyrolysis to break down the waste. The second “resource recovery” facility was briefly slated for Port Chester, but that location was scrapped following public protest by residents of the small village on Long Island Sound.

By 1977 it had become clear that the proposed disposal system only worked if it had a steady supply of trash, and some municipalities were resistant to commit. In mid-1977, with project costs soaring due in part to rampant inflation, Westchester officials struck a deal with the city of Yonkers – the county’s largest municipality – to build the second facility there, in exchange for signing onto the county’s cooperative disposal scheme. The arrangement was critical because it would provide a guaranteed stream of waste to fuel the plant. The proposed site was along Austin Avenue between Route 9A and I-87; next door to the land that a Costco and Stu Leonard’s grocery store now occupy.

Eight miles to the north, the Grasslands plant was about to hit a bump. In March of 1978, DelBello was confronted by an auditorium full of angry Mount Pleasant residents, determined to block the waste burning plant from their hamlet of Valhalla – arguing that it was environmentally unsound technology and would drive down local property values. That summer, the fight moved to the county legislature, where a bipartisan coalition negotiated their own plan to do further studies before deciding which plant – and which technology – to build first.

Sludge Troubles

Meanwhile, another Westchester waste stream was under the microscope: sludge. A 1972 Federal law commonly known as the Ocean Dumping Act caused federal agencies including the EPA, NOAA, the Coast Guard, and the US Army Corps of Engineers to begin looking at the common practice of dumping sludge – a byproduct of sewage treatment – into the Atlantic Ocean a dozen miles off Sandy Hook, NJ – an area known as the New York Bight. At that time, 500 million cubic yards of liquid sludge were being barged from municipal sewage treatment plants in the NYC metro area (including Westchester) and dumped into the seven square mile Bight. Sludge is primarily human fecal matter, but also generally contains a number of harmful contaminants and heavy metals from industry such as cadmium and lead.

By the summer of ‘76, scientists had determined that the sludge was beginning to contaminate Jones Beach on the south shore of Long Island – and the EPA announced it would require an end to ocean dumping of sludge by all NYC-area municipalities by 1981. This set off a series of studies designed to find alternatives. It was already understood that sludge could also be incinerated for around $120/ton, or composted into a form of fertilizer that could be spread on soil, a process that cost $80 – $90 per ton (ocean dumping was only around $30/ton at the time).

A group of eight Columbia and Dutchess County towns, led by 75-year-old conservationist Letty Carson, considered a plan to accept NYC’s sludge for composting and soil application, and by August of 1977, Westchester County was investigating a similar arrangement. The Yonkers sewage treatment plant – at the time handling 60% of the county’s sewage – was being upgraded in a way that would double the plant’s daily sludge output. And the order to stop ocean dumping in the New York Bight by 1981 was on the horizon.

In April 1978, County Executive DelBello revealed a plan to begin barging the county’s sludge from Yonkers to Peekskill, and compost it along the riverfront at Charles Point, on land that Standard Brands (formerly Fleischmann’s, the city’s largest employer) had recently all but abandoned. The proposed site’s 25 acres were part of a 71 acre industrial parcel that city leaders had hoped to exploit as part of an economic redevelopment plan. The sludge plan was revealed to Peekskill’s Mayor Fred Bianco, Jr. and City Manager John Walsh six weeks after the county’s engineering consultants had chosen the site from among 16 considered – and just a month before a May 15th public hearing. Peekskill’s city leaders were furious, and promised a legal challenge. County Legislator Edward M. Gibbs of Peekskill called it “dumping on the north county again.”

Over the following month it became clear that the county faced a major fight. Also becoming evident: there were other, more appealing options for sludge disposal – including a new German technology that could compost the sludge onsite at the water treatment plants, on a small footprint, producing no odors, and produce an ecologically safe end product. On May 15th, just hours before what would have likely been a very hostile public meeting, Gibbs secured an agreement among fellow legislators that would reject the Charles Point site and direct the state’s Environmental Facilities Corporation to consider other locations and technologies, basing the final sludge-disposal decision on economic factors.

One Town’s Trash…

By the fall of 1978, Peekskill’s Charles Point site was back in the news. Seeing EFC and Westchester County increasingly roadblocked from building the Valhalla waste recovery plant, city officials, including Bianco and Walsh, approached County Executive DelBello with an offer: Peekskill would welcome the rejected Valhalla plant at Charles Point – if it came with sizeable property tax payments to the city, and would provide discounted electric power to support nearby industrial development.

The former Standard Brands location was now vacant, and just a mile from ConEd’s electrical substation at the nearby Indian Point nuclear power plant – a substation that would allow the future waste-to-energy facility to push electrical power out into the national grid. The new plant would be privately-built and operated for twenty years, with an option for Westchester County to purchase it after two decades. Eventual tax revenue to Peekskill was estimated at $5 million per year.

By December 1978, county leaders had given up on the Valhalla facility, and some were beginning to turn away from the Yonkers site as well, citing its lack of access to the electric grid (though others argued that a single plant should be located in the more populous southern end of the county, where most of the waste is produced).

A Done Deal

In late January 1979, Westchester County and the City of Peekskill made it official, announcing a $90 million waste-to-energy plant to be built at Charles Point. The new plant would burn all of the county’s solid waste – and its sludge as well – solving two problems at once. And it would generate 35 megawatts of inexpensive electric power, to help promote industrial development in what the NY Times referred to as “the depressed city”.

On February 5th, the Westchester Legislature voted 15 – 1 in favor of a memorandum of understanding that would give Peekskill $3 million in incentives and first refusal on low-cost electricity from the plant. The same night, Peekskill’s Common Council voted unanimously to accept the agreement. In July 1979, Peekskill became the first Westchester municipality to sign onto the county’s plan to accept waste at the Peekskill site, and there was discussion of adding an on-site facility to separate recyclables like metal whose melting temperature makes it a poor fuel for incineration.

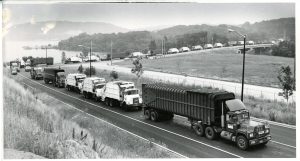

Final approval to move ahead was delayed until late August, when the county finally had agreements with enough municipalities to guarantee the 400,000 annual tons of trash needed to make the plant viable. On August 15th, the final day to reach that goal before DelBello had said the county would abandon the Peekskill plant, the City of Yonkers with its 100,000 annual tons, signed on to the waste plan, pushing it over the top and making the Peekskill plant a reality.

Power to the People

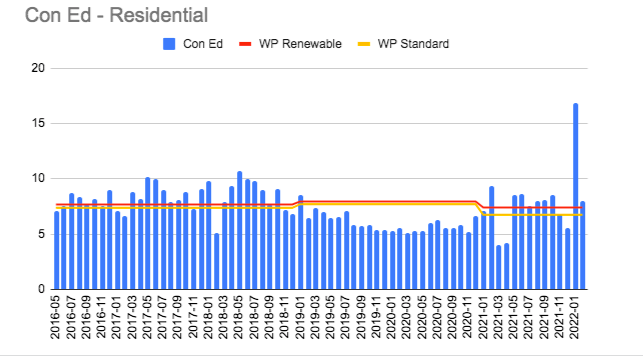

In December 1979, following the defeat of a November ballot measure that would have had Westchester County take over the utility’s electrical distribution system, ConEd announced that it would purchase all of the electricity generated by the Peekskill plant, and pass its savings along to Peekskill residents in the form of lower electricity rates. They estimated the average customer’s electric bill would be reduced by one third.

After initially accepting Illinois-based UOP, Inc’s $100 million bid in June 1980, the county retracted its award citing the company’s reluctance to take on all risk. The following summer the county awarded the project to Wheelabrator-Frye of Hampton, NH, which was already operating a similar facility in Saugus, MA. At this point the project cost had ballooned to $165 million, and Wheelabrator proposed to increase the plant’s capacity from 550,000 tons to 670,000 tons per year, to allow it to receive waste from areas beyond Westchester. The new design would produce up to 60 megawatts of electricity.

On October 15, 1981, ground was broken at the Charles Point site. Construction of the plant began in the spring of 1982, and the first loads of trash were delivered for testing – ahead of schedule – in January, 1984. By then, the total construction cost had risen to $237 million, and the incentives to Peekskill had settled on $1 million a year in lieu of lowered electric rates, plus $1.5 million a year – rising to $3 million after 10 years – worth of payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTs.

During construction, Wheelabrator had merged with Signal, Inc. and formed a joint venture with John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance called Westchester Resco Company (RESCO is an acronym for Renewable Energy Service Company). To this day, many long-time Peekskill residents still refer to the plant as “Resco” – and in fact, the PILOT payments line in the annual city budget is still labeled “RESCO”.

In the years since the 1972 Federal Court order, Westchester County had continued receiving waste at the Croton Point Landfill. Under pressure of a lawsuit by the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association and a new investigation by the US Attorney’s office, the county closed the dump for good on June 30, 1986, and has since capped the 120 acre, 100 foot high pile. For Croton Point Park visitors it is now a giant grass-covered monument to a time when it seemed acceptable to pile trash along the banks of the Hudson River and use a tidal marsh as a repository for our waste. The mound is now a sanctuary for ground-nesting birds, and an important stop along the Atlantic Flyway used by birds migrating from as far away as South America.

Eventually the Grasslands campus in Valhalla did become a node in the county’s waste disposal network: Westchester opened its Household Materials Recovery Facility (H-MRF) there in 2012, to accept items like hazardous chemicals, electronics, and tires from residents.

25 Million Tons

Today, the Peekskill waste-to-energy plant, now known as Wheelabrator Westchester, is surrounded by mature trees atop the hill at Charles Point. From the street, the plant feels innocuous, aside from the steady rumble of tractor trailers and municipal packer trucks that begin arriving at 4 am each day. Its 195-foot mustard-colored smokestack is a local landmark; the plume of white steam a handy reference to the wind conditions along Peekskill’s riverfront. The plant takes in over 700,000 tons of waste per year – though the county says its recycling program has reduced its share of the waste (about 370,000 tons) by 25% since 2003. The plant celebrated 20 million total tons of waste processed in 2015, and will likely hit the 25 million ton mark in 2022.

How did Peekskill residents feel in 1979 when they first heard about the plan for their small river town to play a starring role in sorting out the county’s waste problem?

“Peekskill was in a very bad place then,” recalls Vincent C. Vesce, speaking to the Herald by phone for this piece. A lifelong Peekskill resident, Vesce served on the Common Council from 1982 – 1990 and as Mayor from 1992 – 1994. “There was no development of any type that had happened in many, many years, at least of any consequence. The tax base was regressing.

“The one thing that the Wheelabrator deal was going to be able to do was give Peekskill the promise that its tax base could be solidified. My guess is that was the driving force in the decision.

“There were a lot of people who were skeptical of it, certainly from an air quality standpoint. I had mixed feelings about it. I recognized what it was going to do financially – put a finger in the dike to stop the bleeding.”

In 2013, Wheelabrator built a steam line from the plant, running under John Walsh Boulevard to the new location of White Plains Linen, a long-running Peekskill business which had recently moved to an adjacent industrial park. The two companies had struck a deal whereby the hospitality linen service would buy excess steam from the power plant at a discounted rate to operate their industrial laundry equipment, and in the process avoid using fossil fuels.

Executives from the two companies were presented Westchester County’s Earth Day Award in 2014. The ceremony was held at Croton Point Park, in the shadow of the former landfill.

Categories:

How Peekskill Solved Westchester’s Waste Problem: A Ten-Year Tale of Trash, Sludge, Power and Politics

April 8, 2021

More to Discover