Holtec to Release Radioactive Water

Says it will not wait for state endorsement

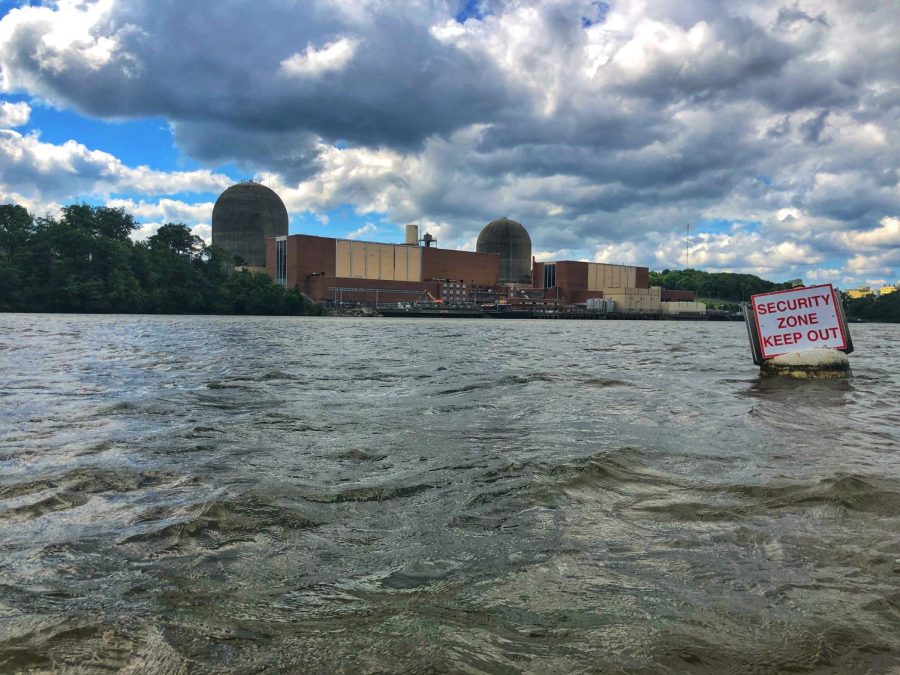

The Hudson River from which seven municipalities source their drinking water and others rely on as a backup source. Highlands Current file photo by Brian Cronin.

February 13, 2023

Editor’s Note: In collaboration with the nonprofit publisher to our north, The Highlands Current, we are publishing this story concerning the decommissioning of Indian Point.

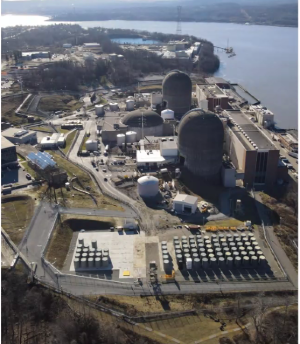

Holtec International, the company decommissioning the Indian Point nuclear power plant near Peekskill, announced at the Feb. 2 meeting of a state board overseeing its work that it plans to release radioactive water into the Hudson River before autumn.

Although filtered, the water will contain tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen difficult to remove. The firm says the release will cause minimal problems because the water will disperse, and an engineer on the Indian Point Decommissioning Oversight Board said it may be the least-worst option to empty the plant’s cooling pools.

At the meeting of the oversight board, Rich Burroni, a Holtec representative, said that the company plans to release the water in late August or early September, although he would not rule out dumping it sooner.

“We may be real efficient and be able to move it up,” he said. In a follow-up statement to The Current, Holtec said that the amount of water that would be released has not been determined.

Burroni was asked by Richard Webster, a member of the oversight board who works for the environmental group Riverkeeper, if Holtec would consider delaying the release until the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) gave its support.

“Full transparency? No,” Burroni replied. “I’m not going to sit here and tell you a different story. We want to meet this 12- to 15-year requirement” to finish the decommissioning and return the land to the Village of Buchanan. “I understand the emotional part about the discharge to the river,” he said.

Burroni later said he would be willing to discuss the matter with community members at a smaller meeting, and that Holtec would provide a month’s notice before the wastewater was released.

“I’m not going to appease everybody,” he said. “But at least we have some basic science and some basic facts behind what we do.”

Holtec may also have the law behind it. The state DEC only regulates the non-radioactive materials that Holtec discharges. The radioactive materials are under the authority of two federal agencies: the Environmental Protection Agency and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Throughout the evening, members of the oversight board repeatedly said that members of the public concerned with Holtec’s plans should contact the EPA or NRC. In Massachusetts, the EPA has put a hold on a Holtec plan to discharge radioactive water from the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant into Cape Cod Bay until a third-party can verify that the release would be safe.

No risk-free options

During the meeting, Dave Lochbaum, a nuclear engineer and former director of the Nuclear Safety Project for the Union of Concerned Scientists who serves as the oversight board’s technical expert, outlined his reasoning that releasing the treated water into the Hudson poses the least public risk.

Boiling the water to evaporate it, as was done at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania in the early 1990s, would release the radioactive material into the air instead of the Hudson, where it has a greater potential of being ingested or inhaled, he said.

Lochbaum also argued that if burying the wastewater in Idaho is considered safe, it might as well be buried in the Hudson Valley.

The wastewater also could be stored in tanks at Indian Point. Tritium has a half-life of 12.5 years (as opposed to the thousands of years of other radioactive materials), so a release could be delayed until it has decayed.

But Lochbaum cautioned against this. He explained that the water tanks would have to be vented, meaning that some radioactive material would be constantly evaporating into the air. And the tanks used to store radioactive wastewater are notoriously leaky: At Vermont Yankee, a tank failure led to 83,000 gallons draining into the Connecticut River. At Browns Ferry in Alabama, the gauge that was supposed to detect if the tank was leaking failed, and the leak was only discovered when a building next door began filling up with radioactive water.

Lochbaum said that there have also been numerous cases in which a tank leaks even as it’s being filled, and technicians keep filling the tank anyway. “You’d think it shouldn’t happen more than once,” he said. “But while lightning may only strike once, stupidity strikes like a jackhammer.”

If Holtec releases the water from the pools into the Hudson, it wouldn’t be the first time. In 2009, Entergy, which owned Indian Point at the time, emptied the cooling pool at Indian Point 1, which had closed in 1974, into the river. (The two remaining reactors closed in 2020 and 2021.) And tritium has been released into the Hudson by Indian Point every year, at levels far below the maximum allowed. Lochbaum estimated that even multiplying the estimated levels of radiation that would be released into the Hudson by the pool’s wastewater by 10 would still be less than 5 percent of the allowable limits.

That’s assuming you accept the validity of the federal limits, and a number of speakers did not, noting that the standards have not been updated in 50 years and were calculated by estimating the effects of radiation on healthy white men in their 20s and 30s — essentially, the scientists working on the Manhattan Project. It’s unknown if women, children and the elderly would be more vulnerable. The state DEC, for example, sets limits based on a person’s age and gender for how many fish from the Hudson can be consumed each month as a result of ongoing PCB contamination.

Speakers also suggested that any effects of radioactive water should be considered in conjunction with other environmental contaminants, such as the poor air quality from Peekskill’s WinWaste Innovations incinerator and the fact that the Hudson River has been officially classified as a Superfund site by the EPA for nearly 40 years.

Releasing the water into the Hudson, they argued, is being pushed by Holtec not because it’s safe but because it’s cheap and easy. “All the cost goes on to the public,” said Michel Lee, an attorney who works with United for Clean Energy. “All the benefit would go to Holtec.”

Two other disposal options came up during the meeting. One would involve keeping the pools filled until all of the other radioactive material was moved off-site. This would not only give the tritium time to decay, but serve as a fail-safe if a dry cask that stores the spent fuel failed and needed to be cooled immediately.

“That’s not our business model,” Burroni responded.

The other option would involve having the federal Department of Energy filter the tritium from the water, an expensive proposition. State Assembly Member Dana Levenberg, a Democrat whose district includes Philipstown, asked what would happen to the tritium.

“You’re not going to like this,” Lochbaum said. “It’s used to make nuclear weapons have bigger bangs.”

“That’s why they call it ‘H-bomb boiling,’ ” added Webster, of Riverkeeper.

Near misses

Later in the meeting, Burroni revealed that the NRC recently cited Holtec after a federal inspector discovered that an equipment hatch did not have adequate controls to ensure that radioactive emissions would not escape. The issue has been remedied, Burroni said. “This was a good lesson learned for us,” he said.

“Did those lessons include finding out why your team didn’t find this problem before the NRC inspectors did?” asked Lochbaum.

“We could’ve done a better job there, Dave,” said Burroni.

Burroni also said he was “not proud of” the fact that, in the past few months, the plant has had two “near-miss” events and three work-related injuries. In a follow-up with The Current, Holtec said that the near-miss events were a rigging device that broke while lifting a load, and a lifted load that went too close to workers.

Holtec said the causes of these events included workers using the wrong tools, faulty body posturing and hand/eye coordination, a pre-existing condition (a worker re-injured a shoulder) and the material condition of the facility.

Its corrective actions include designating a “coach of the week” to ensure standards are being met, and better housekeeping procedures. “I was disappointed in some of the housekeeping things I saw,” said Burroni. “I’ve told all the guys, and everybody acknowledges, that just because we’re a decommissioned plant it doesn’t mean we let our standards go.”

Sinking farther

Holtec was not the only company on the hot seat at the meeting. Enbridge, the firm that oversees a 1,129-mile natural gas pipeline that passes under Indian Point, was asked about a sinkhole that opened over the pipeline on Dec. 24 in a park in Yorktown.

John Sheridan of Enbridge said the only damage to the pipeline was an abrasion, “similar to a scratch that you would get on your hand,” and that it remains in good condition. He said that he had no information about the cause of the sinkhole.

Tina Volz Bongar, a community member who had made a presentation at a previous oversight board meeting about the inconsistencies between Enbridge and Entergy’s emergency plans, noted that Enbridge’s monitoring systems failed to detect the sinkhole, and that the company only found out after a Yorktown resident walking a dog called the police.

“That tells you what Enbridge’s integrity-management system really is,” she said.

Webster asked if the sinkhole occurred in an area where Enbridge knew sinkholes were a possibility.

“I don’t have that information this evening,” Sheridan said. “I hate to speculate until we have all the facts in front of us.”

“You should have had the facts before you put the pipeline there,” replied Webster.

The next meeting of the Indian Point Decommissioning Oversight Board is scheduled for April 27.