V.L. Cox Uses Art to Open Minds and Hearts

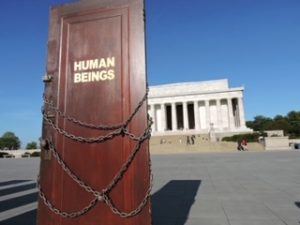

Cox took her End Hate exhibit to the National Mall in April 2015.

April 7, 2022

V.L. Cox, an artist who moved from Arkansas to Peekskill last April, believes in the power of art. “I have learned that the arts have the ability to cross religious and political boundaries with ease when all other means of communication fail,” she told the Peekskill Herald. She speaks from experience.

Cox, 59, was living in Arkansas in 2015 when the legislature was considering a bill called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). “This bill would have taken us back to Jim Crow Days,” Cox said. But in addition to discriminating based on the color of your skin, this bill was “expanded to not only race, but gender, sexual orientation, and even different religions or beliefs.”

Cox viewed the bill as a direct attack. “As a lesbian who was in a 20-year relationship at that time with children, my family and I could’ve been denied lifesaving medical care, a sandwich in a restaurant and even gasoline or automotive services if we were traveling.” Cox knew what she had to do. “It was an unjust bill that needed to be stopped so I went public and used the loudest and most powerful voice I had. My work.”

Cox then created “End Hate Doors.” This art installation was a series of doors labeled as to who may enter. In the artist’s words, the series is “based on the labels once placed on doors, not that long ago, from our shameful past. These doors … remind others of how dangerous and repressive the labels of discrimination can be, and how everyone deserves the right to walk through any and ALL doors with dignity and respect.”

The project was installed twice on the steps of the Arkansas State Capitol as a First Amendment protest. Images of the installation rapidly spread through news and social media sites and helped bring attention to the struggle for equal rights. In the end, much of the bill was defeated. Cox then got permission to bring the installation to the Lincoln Memorial. There she witnessed firsthand the power of art to open the lines of communication.

She was at the event when a giant of a man with white supremacist tattoos approached her. “As I stood there like a statue, this giant of a man extended his hand and spoke in a deep, gentle voice. ‘I want to thank you for what you are doing,’ he said. ‘I was born into the Klan in South Georgia. My father and brother are still in the Klan there. My wife and I fled under the cover of darkness because they were going to kill my son, who is transgender.’” Cox says she caught her breath, “grasped his hand, and realized that if that man could change his heart, anyone could.”

The doors became part of a 50-plus piece installation project that travelled more than 100,000 miles around the country before the pandemic. It is now out of “pandemic storage” and in Cox’s live/work studio in Peekskill.

Cox not only believes in the power of art to open minds; she believes it can save lives. Cox was always an artist—one of her earliest photographs shows her two-year-old self drawing at a chalkboard with her father—and often drew and daydreamed at school. Because of this she was punished, ridiculed, and even called “brain-damaged” by one teacher. The artist also had a challenging home life. She had an addicted and abusive mother and lived with constant parental turmoil.

Cox’s grandmother saved her. One way she did this was by recognizing and encouraging Cox’s artistic talent. She signed Cox up for an art class for children at nearby Henderson State University when Cox was ten. Cox created her very first art portfolio that summer and found it at the bottom of her beloved grandmother’s cedar chest after she died.

“I would like to have an exhibition at some point with these pieces to show how a little creative support and encouragement can literally change a child’s life,” Cox said. “If it weren’t for my grandmother who saved me from an abusive situation and saw my talents and interest through the stifling veil of society, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Cox has been a professional artist for more than 30 years. She has had and continues to take numerous commission orders to sell to corporate and private collectors. After seeing the powerful impact of her 2015 “End Hate Doors” exhibit, she also continued to focus on civil rights and social justice.

Cox’s most recent installation, “Watchfires,” opened at the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, this past January. The museum describes the exhibit as “featuring works that employ authentic and found objects to comment on social justice and human rights issues that are still relevant today.” Cox points out that a watchfire is a fire maintained during the night as a signal or for the use of someone who is on watch.

“The separation of our country has reached a dangerous level, and a deadly global pandemic added to the equation has made it worse,” Cox says, “I feel now, more than ever, we need the Watchfires to burn again through the night. To light up the darkness as a beacon of hope, strength, freedom, equality, and civility.”

It was threats to freedom, equality, and civility in parts of the South that helped lead Cox to move from Arkansas to Peekskill. She was aware of the artists’ community here from visits to New York and friends in the area. Cox says that “when the vaccines were available and the political climate in the South was turning cruelly sour, where we lost everything we had gained in 2015, I called a friend and told her I had had enough, and I was finally ready to leave.” She came to Peekskill and calls it “one of the best moves I’ve ever made.”

“Being an adventurous, outdoor, farming country girl at heart who grew up in a small southern town, Peekskill has been perfect for me. I am surrounded with beautiful rivers and mountains which I’m accustomed to, yet have access to the city for museums, creative adventures, and business,” Cox says. She adds, “I love the diversity and the creative people here who have warmly embraced me. And between my two favorite places—the Peekskill Coffee House and the Beanrunner Café, I have been kept well fed and pleasantly caffeinated.”

Working towards her “Watchfires” opening kept Cox too busy to get out and explore much, but she is making up for lost time. “I love the Bruised Apple bookstore, drive around to different villages, walk down by the river, and frequent Depew Park.”

Cox looks forward to the warmer weather for many reasons, several of which revolve around her large balcony. In addition to continuing to pursue her passion for growing tomatoes (in pots now, rather than on the quarter acre lot she’s used to), she has also gotten permission to have small private showings on her balcony. She also hopes to find large art spaces for installation exhibits in the New York area.

“The Peekskill studio gives me a new start, a new perspective, new adventures, and new experiences in one of the most historical locations in our country,” Cox says. “I have barely begun to scratch the surface here creatively.”