By August, every gardener has made a sacrifice to some kind of bug. Whether it’s the tear that slipped when your year-old cherry tree was mobbed by spotted lanternflies or the mosquito-raised welts that followed you inside from watering, coping with insects is part of gardening. As pesky as these beings are, without them, we’d be without our gardens — and certainly without our food.

So how can you avoid insect pests in the garden while sparing fireflies, monarch caterpillars, and bees? Let’s take a closer look.

Bug Buddies: The Good Guys

Scientists estimate that 70% of crops eaten need pollinators to yield food. And yet, studies show that there’s been at least a 75% decline in flying insect populations in almost three decades. The culprits include use of pesticides, habitat loss, the introduction of harm via non-native insect populations, and climate change.

Recently, researchers found that dead overwintering monarch butterflies had an average of seven different pesticides in their bodies. Pesticides such as neoconicotoids and pyrethins are derived or synthesized from vegetable sources, so they can be marketed as “natural” but are universally lethal: The same poisons that render your yard mosquitoless indiscriminately harm “good” bugs as well.

Lightning Bugs, aka Fireflies: While these insects are neither bug nor fly (they’re actually a type of beetle in the Lampyridae family), they are undeniably part of the magic of summer. But they’re getting harder to find. How can gardeners invite this charismatic creature back into the yard? Stop use of any broad-spectrum insecticides, leave the leaves to ensure ideal habitat for their offspring, and encourage levels in your plantings — different types of fireflies thrive in different settings.

Bees: It’s common knowledge that bees are prolific pollinators and that their numbers are in decline: the nonprofit SavetheBees.org cites that in the last 75 years, global bee numbers have decreased more than 50%. What may also surprise you is that the honey bee one imagines pollinating their tomato plant isn’t even native to the States to begin with, and isn’t at risk of extinction.

European Honey Bees (Apis mellifera)

This domesticated species, responsible for all of the honey produced commercially, was introduced to North America by colonists in what is now Virginia who were interested in replicating the agriculture of Europe. Golden, with a fuzzy thorax, and between 0.5 and 1 inch long, these creatures escaped their initial service in Jamestown’s gardens and spread throughout North America.

Apis mellifera are generalists capable of thriving in a multitude of ecosystems, meaning that they can crowd out species that coevolved in more specialized settings. Because they’re managed by humans at a commercial scale (whether for the liquid gold of their honey or their lucrative pollination services, or both), as long as we’re around, these animals will probably never go extinct.

Despite this, many honey bee colonies in North America have been wiped out by Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), an as-yet not fully understood occurrence where drones (aka worker bees) abandon their queen, ending the viability of the hive. In addition, and perhaps as a factor of CCD, infestations of parasitic Varroa mites can infect them with a virus that weakens the bees’ bodies. Not only are they decimating many domestic honey bees, these mites have been found in various native bee populations, threatening their already precarious position.

Native Bees

Ranging in size from a rice grain (such as the green sweat bee) to walnut-sized (like the Eastern carpenter bee), North American native bees are diverse. Some live solitarily in walled-off cells while others are social, dwelling in hives like those of the European honey bee. Some sting, and some don’t. As their range in size and behaviors suggest, these bees are often specialists — they thrive best with the plants they coevolved with, which grew most readily in specific ecosystems.

Many of these plants are harder and harder to find because the pollinated and the pollinators are inseparable: the fewer we have of one, the fewer we have of the other. Biologists wonder if the loss of our niche flora and fauna has started a negative cascade, which once started can’t be reversed. As conservationist Aldo Leopold says, “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.” I learn to count the types of bees in the native wildflowers ringing my garden and celebrate the diversity I can witness in this stage of the Anthropocene.

In this spirit, gardeners would do well to invite as many types of bees, native or otherwise, into their spaces.

This means planting a range of types of plant species, both exotic and native, and eschewing any pest management practice that could harm them. It could mean learning about hive management and joining a group of local beekeepers, who work together to manage Varroa mites without pesticides, or it could be as simple as leaving the grass under the paper wasp’s nest unmowed for the summer if possible. (Yes, wasps, yellow jackets, and hornets are also vital pollinators, and hives seasonally die off after a frost.) It means allowing wild patches in your yard that include dead branches, leaf litter, and other “unmanaged” spaces to promote apian life.

Your veggies will thrive in a garden that attracts bees: the more pollinators, the more flowers are turned into fruit. Some great candidates for attracting bees that also self-sow for minimal work include calendula, borage, chamomile, and the better-behaved Asclepias such as A. incarnata and tuberosa. These have the added bonus of attracting other beneficial bugs, as well.

Ladybird Beetles: These insects, long considered a symbol of luck, should be welcome guests in every garden. While not called ladybugs by entomologists, ladybird beetles eat aphids, spider mites, and other soft-bodied insect pests that prey on everything from prize roses to snap peas.

Ladybird beetles’ voracious appetite for these pests as well as flower nectar can be used to gardener’s advantage by planting a flat-topped plants like dill, fennel, yarrow, marigold, sweet alyssum, sunflowers, calendula, and cosmos. Be sure to familiarize yourself with the different instars or stages of ladybird beetle development, as earlier instars bear little resemblance to their shiny red adult forms.

Bad Bugs: Shoo, Spotted Lanternfly, Don’t Bother Me

Having established the intrinsic ecological necessity of some beneficial bugs, let’s take a look at the true pests in our gardens and explore some ways to avoid them.

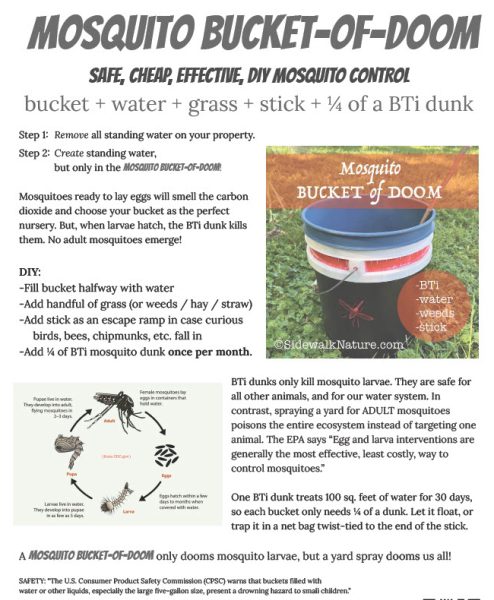

Mosquitoes: These whining pests are also pollinators — both male and females feed on nectar, while the females also require blood. To spare your skin the itchy bumps their saliva produces, first get rid of all inessential standing water. Then, set up a few mosquito dunk buckets.

Mosquito dunks are available online and in garden centers and look like the grey love child of a mini doughnut and a cardboard box, but are actually a dormant torus of Bacilus thuringiensis, a bacteria that occurs naturally in everything from tree bark to caterpillar guts. These are essentially watery mosquito traps that lure mosquitoes into their depths to lay larvae — except the water has been augmented by Bti to incapacitate mosquito young but leave other organisms unaffected.

It’s true that your mosquito dunks will require a few minutes a week to reset, but the reward — more summer hours spent enjoying your yard in peace — also benefits countless invertebrates who call it home.

Spotted Lanternflies: An insect pest that’s been on the rise in our area in the past two years, spotted lanternflies (SLF) (Lycorma delicatula) are considered environmentally problematic because they’re introduced from another region and especially love fruit trees. SLF are sap-suckers, preventing plants from thriving. Their waste or honeydew promotes the growth of fungal disease.

Besides stomping them on sight (which can be tricky, given their propensity to hop out of reach), some gardeners choose to employ lanternfly tape, which wraps around tree trunks that lanternflies traverse to breed and lay eggs. Two to three strips of tape are attached at regular intervals about 4 to 6 feet off the ground, and lanternflies are trapped as their feet touch the sticky surface.

While this method traps SLF, it may capture many other organisms, including beneficial insects and birds. If you choose this method, keep a close eye on it.

Another method seeks to prevent SLF infestations by scraping egg masses into plastic bags treated with a few squirts of hand sanitizer. Look for these masses everywhere from tree trunks to concrete curb blocks in autumn, then use an old plastic card to scrape them, being sure to pulverize them within the bag. Because SLF lay egg masses close together, many can be dispatched at once. (Given that October is prime SLF egg mass hunting time, you might qualify this as a gory yet seasonally appropriate type of egg hunt with young folks.)

So before you swat a small six-legged visitor, take a moment to see it. What kind of bug are you dealing with? How might it help your garden? And how might you, in turn, help good bugs thrive?

Garden News: Interested in adding to your beneficial pollinator garden? Visit Rosedale Nurseries for the 16th Annual Native Plant Weekend on September 6 and 7 from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Shop a wide selection of native plants for your garden with help from their personal shoppers and attend free talks by native plant experts.

Want to share a picture of your Mosquito Buckets of Doom? Email Lucy at [email protected]!

![Peekskill girls volleyball in action against Fox Lane on Oct. 16. (Peekskill City School District]](https://peekskillherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Lead-photo-6-1200x640.jpg)