In Part Two of a two part look at Wheelabrator Westchester’s waste-to-energy plant in Peekskill, we examine the costs, benefits – and potential alternatives to the current system.

The Frit Pit

From the plant’s opening in 1984 until October 22, 2009, Wheelabrator’s ash output had a much shorter journey than it does today. For 25 years, the remnants of the waste-to-energy operation were landfilled just four miles from Charles Point, at the Sprout Brook Residue Disposal Facility, off Albany Post Road, just beyond the “rock cut” in Cortlandt. Five days a week, trucks brought 400 to 600 tons of ash to the 30 acre county-owned site in the narrow valley just north of Peekskill. According to a 2009 NY Times article on the closure, the site took in around 15 million tons of ash in that period.

Locals wryly refer to the massive pile, now capped with a protective lining and monitored for offsite leachate, as “the Frit Pit.” From the town athletic fields along Sprout Brook Road, the “pit” is much more a pile – a light gray butte towering behind a thin strip of forest that disappears into the valley as it extends northeast out of view. The site began as former gravel mines (hence the “pit” moniker), but today the ash pile rises to the height of surrounding ridges – roughly 200 feet, based on topographic maps.

At the base of the massive pile, Sprout Brook, a valley stream which joins Annsville Creek just upstream of the Hudson River, winds its way through Sprout Brook Park. The park is a four acre sliver of land wedged between Sprout Brook Road and the ash pile; it was given to the Town of Cortlandt by the county as a token of its appreciation for hosting the final remnants of Westchester’s waste in perpetuity. Unlike Peekskill’s arrangement for hosting the waste-to-energy plant, Cortlandt never received direct financial compensation for hosting the ash dump.

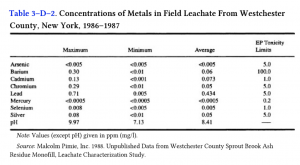

At the time of its closure, the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) promised to monitor the Sprout Brook Ashfill, including adjacent ground water, for thirty years. There’s very little publicly available information about the leachate test results, other than this table from a 1989 book, from samples taken just two years after the facility opened.

A 1993 edition of environmental watchdog publication “Waste Not” mentions that a mile-long pipe was laid “within the past two years” “to run the leachate from the landfill in Cortlandt to the Peekskill sewage treatment center” (which is operated by Westchester County at Annsville Creek). This seems likely to be true, given that the Peekskill Sewer District extends beyond the city limits in this area, fully encapsulating the ashfill.

Since October 2009, the ash from Wheelabrator’s Peekskill plant has been trucked 150 miles east down I-84 to a company-owned ash monofill overlooking the Quinebaug River in Putnam, Connecticut. That facility, which opened in 1999, takes in 575,000 tons of incinerator ash per year, from waste-to-energy plants in New York and Connecticut. Wheelabrator pays around $3 million per year to the town of Putnam for the arrangement.

In 2019, with the monofill expected to fill completely by 2024, Wheelabrator announced a plan to expand the Putnam operation by 68 acres, giving it another 25 years worth of capacity. The proposal, which includes filling and re-creating a 7 acre wetland, caused intense debate in the rural Connecticut town of less than 10,000 residents. In the end, Wheelabrator offered some concessions including a 48 acre conservation area. The town’s Zoning Commission approved the expansion in September, 2020.

Up in the Air

From its 1984 opening, Peekskill’s Westchester Resco operation hummed along pretty quietly, with little news coverage for the first few years. But in the late 1980s, the problems of air pollution and ash disposal from a rapidly growing fleet of “resource recovery” and “waste to energy” incinerators became a topic of increasing debate in the US.

In early 1988, environmental advocacy group Environmental Defense Fund filed a federal lawsuit against Wheelabrator Technologies, accusing the company of violating state and federal laws requiring incinerator ash from its Peekskill plant to be handled as hazardous waste. The case ran for over five years, and in 1994 the US Supreme Court effectively ruled that incinerator ash is hazardous waste, and must be handled and disposed of accordingly.

Others were beginning to look at what was leaving incinerators via their smokestacks, escaping into the air. Experts began tracking releases of compounds like hydrogen chloride, and dioxins – tiny particles believed to cause cancer, even in small quantities.

When the Peekskill plant opened, it had relatively simple emission controls – electrostatic precipitators or ESPs – generally considered an effective way to capture small particles like fly ash. But 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act of 1970 established a new standard called MACT or Maximum Achievable Control Technology. According to the EPA, “Under MACT standards, the technology and work practices in facilities that produce the lowest HAP (hazardous air pollutants) emissions are used to set the standards for the rest of the industry.”

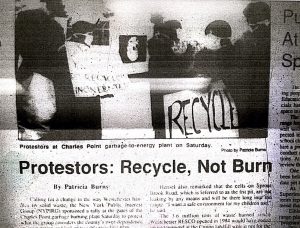

That meant that as new technologies were developed that were more effective at cleaning the gases being released by plants, companies like Wheelabrator had a legal obligation to upgrade their equipment. A 1989 Peekskill Herald article covered a protest at the Charles Point plant sponsored by the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), with area residents urging the county to not spend millions upgrading the plant, but to invest more in recycling.

For this article, Wheelabrator told the Herald that during a 1999 upgrade, they installed spray dryer absorbers and fabric filters, carbon injection, and urea injection for NOx control. According to a 2011 case study by Governmental Advisory Associates (GAA), the retrofit cost $75 million, with the Westchester IDA covering $64 million, and Wheelabrator covering the $8 million balance.

While it’s certain the plant produces less emissions today than it did before the retrofit, according to the EPA it is still a significant polluter.

NOx-ious Gases

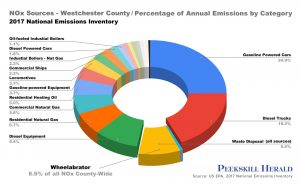

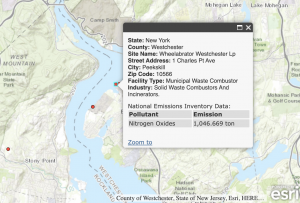

The most recent emissions data we were able to obtain was from the 2017 National Emissions Inventory (NEI). It’s a comprehensive inventory of virtually all known US air pollution sources (both mobile sources like planes, ships, cars and trucks; and point source emitters such as airports, factories, power plants and incinerators). A new NEI is issued every three years, but updates to the previous NEI are made regularly. The 2020 NEI is still in development and hasn’t yet been released.

In creating the Emission Facts graphic below, the Herald examined all of the EPA’s 2017 NEI emission values for Wheelabrator Westchester, and included the most significant releases. To the best of our understanding, all of the releases were within the legal allowable limits set by the EPA and the Clean Air Act.

According to the EPA’s “Green Book” which tracks air quality based on the measured amount of CAPs on a county level, Westchester County’s air is currently below maximum thresholds for carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, particle pollution (PM10 and PM2.5), and sulfur dioxide. But the county (along with Chautauqua, Rockland, Nassau, Suffolk and the five boroughs of NYC) has failed to meet minimum standards for ozone pollution over the last several years. According to the EPA, “Tropospheric, or ground level ozone, is not emitted directly into the air, but is created by chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOC). This happens when pollutants emitted by cars, power plants, industrial boilers, refineries, chemical plants, and other sources chemically react in the presence of sunlight.”

Looking closer at the EPA data for Westchester County, the waste disposal sector accounts for around 9.5% of all NOx emissions annually – and Wheelabrator Westchester contributes over 94% of that amount. The 1,046 tons of nitrous oxides it released in 2017 represents just under 9% of the county’s annual total NOx emitted from all sources. Combine that with the VOCs – produced mainly by the use of fossil fuels as well as natural sources like trees – and you’ve got a recipe for high ozone levels and poor air quality, especially in the summer.

Wheelabrator’s Peekskill facility is a heavy-hitter when it comes to NOx emissions statewide, too: in the 2017 NEI, the Charles Point plant ranked fourth in New York State, after JFK Airport; the RED-Rochester power plant upstate (which has since replaced its coal-fired boilers with natural gas); and Covanta’s waste-to-energy plant in Hempstead, Long Island.

It should be noted that the plant’s 2016 permit renewal (which runs through December, 2021) allows up to 1,066 tons of NOx emissions annually. The 2017 NOx release falls within that limit.

Emission Facts

When it comes to other air pollutants, Wheelabrator is one of several contributors in the Peekskill area, including the BASF plant less than a half-mile away; and the LaFarge Gypsum plant, that manufactures drywall for construction just a mile down the Hudson River shoreline in Buchanan.

For most measured compounds besides nitrous oxides, Wheelabrator is a minor contributor. For example, in the PM2.5 category (fine inhalable particulate matter 2.5 microns and smaller), at just under eight tons released, Wheelabrator didn’t even make the top 50 offenders for New York State in 2017. This at odds with a statistic presented in a November 2020 Tishman Environment and Design Center document claiming that “In  2017, Wheelabrator Westchester was the largest emitter of PM2.5 emitting 15,911.15 lbs” According to the NEI, Wheelabrator’s seven tons was dwarfed by nine other NY State plants, each emitting over 100 tons apiece.

2017, Wheelabrator Westchester was the largest emitter of PM2.5 emitting 15,911.15 lbs” According to the NEI, Wheelabrator’s seven tons was dwarfed by nine other NY State plants, each emitting over 100 tons apiece.

One exception at Wheelabrator Westchester is its output of benzo[a]pyrene, a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and known carcinogen that according to Wikipedia, “can be found in coal tar, tobacco smoke and many foods, especially grilled meats.” This is one of the things in cigarettes that makes them cause lung cancer, and also the reason you’re not supposed to eat the burnt ends from your weekend barbecue.

The Peekskill incinerator ranked third in the state for emissions of benzo[a]pyrene in 2017, just below the waste-to-energy incinerators in Hempstead and Niagara Falls, with 164.6 lbs of the stuff emitted. After the three incinerators, nobody else was even close – the next-worst offender, International Paper in Ticonderoga, released just two pounds of BaP. That said, we suspect the 2017 numbers were an aberration: in earlier NEIs from 2008, 2011 and 2014, the plant reported outputs of less than a pound a year.

The plant also reported significant (but legally allowable) releases of toxic metals such as mercury, cadmium, and lead in the four available NEIs.

River Impacts

Like most power plants of its vintage, waste-to-energy plants like Wheelabrator were almost always built on the shoreline of a river, lake, or other body of water. That provides the operation a cheap, dependable source of cool water to condense the heated boiler water and produce steam.

We asked Wheelabrator about how the plant impacts the Hudson River in Peekskill, and they explained “We draw water in from the Hudson River to cool down the steam from our turbine generator. Following a well-regulated process that establishes guidelines for temperature and volume, the water is then returned to the river through a permitted diffuser designed to minimize impacts on the river.”

We asked Wheelabrator about how the plant impacts the Hudson River in Peekskill, and they explained “We draw water in from the Hudson River to cool down the steam from our turbine generator. Following a well-regulated process that establishes guidelines for temperature and volume, the water is then returned to the river through a permitted diffuser designed to minimize impacts on the river.”

Dan Shapley of Riverkeeper, (an environmental advocacy organization whose main focus is on the health of the Hudson River), provided the Herald with a publicly-available copy of the NY State DEC permit that covers this aspect of the plant’s operation, allowing Wheelabrator to intake and expel Hudson River water for cooling. Under the Clean Water Act, explained Shapley, such permits are supposed to be reviewed every five years – with stricter standards each time, to ensure that environmental impacts are reduced over time. But according to what’s publicly available via the DEC’s website, Wheelabrator’s permit for the Peekskill operation appears to date back to 1995. The permit is current and valid, having been renewed most recently in December 2020 for another five years. But there’s no evidence of any changes or stricter standards implemented since 1995.

The plant’s DEC permit allows the intake of up to 55 million gallons per day of Hudson River water (which is a lot, but pales in comparison to Indian Point’s 2.5 billion gallons per day). According to Shapley, this sort of intake – especially if the plant isn’t using the most advanced mitigation equipment – typically results in the death of any fish or other aquatic life that gets sucked in by the plant’s water pump. Other larger power plants on the Hudson have been required to install equipment to reduce their impacts in recent decades.

It’s unclear what, if any, improvements have been made to the plant’s intake systems over the years, but based on language in the 1995 permit, it doesn’t appear that the plant is currently required to provide any mitigation to protect the aquatic life of the Hudson River.

The river water passes through heat exchangers, cooling the plant’s superheated boiler water to produce the high-pressure steam that drives the plant’s generator. In the process, the cool river water absorbs some of the heat. Wheelabrator is allowed to return water to the river that’s as hot as 105º F (93.2º F in May and June) – significantly warmer than the river’s natural water temperature, which averages in the lower 40’s in the winter and reaches as high the mid-80s in summer. Per Shapley, this too has detrimental effects on the river’s ecosystem, disrupting the natural environment for aquatic plants and animals.

What’s In It for Peekskill?

According to the city’s 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), Wheelabrator Westchester paid the City of Peekskill $5,729,068 in payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) for their Louisa Street operation. They pay a PILOT rather than traditional property taxes in part because the land on which the plant stands actually belongs to the City of Peekskill Industrial Development Agency (IDA). But PILOTs also are also often used as a financial incentive to lure new businesses and developments: in Wheelabrator’s case, the 2019 property tax bill on the plant would have been $12,657,098; with the tax abatement created by the PILOT, Wheelabrator saves nearly $7 million per year.

During the January 26th meeting of the Peekskill IDA, it was mentioned that the land at 3 John Walsh Boulevard (the parcel on which Wheelabrator sits) has been carrying an assessed valuation of only $250,000 since the early 1980s. The IDA recently had the parcel re-assessed by an independent assessor, who valued the property at $10.25 million.

The PILOT is earmarked to support local public schools; around 64% of the annual revenue ($3,647,022) goes to the Peekskill City School District, with the remaining 36% ($2,082,046) flowing into Hendrick Hudson’s school budget (a portion of the plant lies within the HenHud district). Peekskill’s portion represents about 3.8% of its annual school budget.

It’s unclear why HenHud receives such a significant percentage of PILOT funds from a business that’s fully within Peekskill’s borders. In contrast, the Buchanan-centric district funds a third of its budget from a $24 million annual Indian Point Energy Center PILOT – a source from which Peekskill receives nothing. A long time Peekskill resident speculated that the Hendrick Hudson district may have encompassed more of the plant when it was first opened, and the borders may have been redrawn in the intervening years.

Energy Justice

Some environmental justice organizations like Energy Justice Network and GAIA believe municipal waste incinerators like Wheelabrator Westchester are destructive relics that should have been retired years ago. At a recent meeting of Peekskill’s Conservation Advisory Committee, Energy Justice Network’s Mike Ewall, Paul Presendieu and Dante Swinton presented a number of statistics to support their case:

- No new municipal solid waste incinerators have been built in the US in 30 years

- The average waste-to-energy plant’s retirement age is around 23 years; Wheelabrator Westchester is now 36 years old.

- WW’s 10 year contract extension in 2019 means that by 2029 it will be the oldest such operating facility in the US

GAIA, a “worldwide alliance of more than 800 grassroots groups, non-governmental organizations, and individuals in over 90 countries” that advocates for a “zero waste” future, has published dozens of fact sheets that seek to refute the idea that municipal waste incineration is a sustainable, long-term fix for what they term an “extractive economy”. Their recent report, “Failing Incinerators” says that incinerators emit 68% more greenhouse gases per unit of energy produced than coal-fired power plants, and also states that approximately eight out of ten US incinerators are located in so-called “environmental justice” communities.

Environmental Justice communities are defined as communities most impacted by environmental harms and risks, and generally are areas where negative environmental factors such as pollution intersect with at-risk communities such as the poor, minorities, and indigenous populations, to result in a local population that is often “overburdened” by the combination. One frequent result is higher-than-average health disparities.

Environmental Justice communities are defined as communities most impacted by environmental harms and risks, and generally are areas where negative environmental factors such as pollution intersect with at-risk communities such as the poor, minorities, and indigenous populations, to result in a local population that is often “overburdened” by the combination. One frequent result is higher-than-average health disparities.

Much of Peekskill has been designated a “Potential Environmental Justice Area” by the New York State DEC’s Office of Environmental Justice, making those neighborhoods eligible for certain grants and environmental improvement programs.

For Vanessa Agudelo, a Peekskill Common Council member and social justice advocate, there’s no debate. “Peekskill’s financial gain over the years does not come close to the deadly health and environmental impacts our residents have to live with because of this facility,” said Agudelo in an email to the Herald. “As the number one polluter in all of Westchester County by six times, this incinerator has greatly contributed to Peekskill’s alarmingly high rates of asthma and infant mortality, shockingly disproportionate to that of the rest of the county. Our communities do not need more garbage incinerators. What we need are programs and incentives that promote composting and recycling, and substantially scale back the amount of waste produced so that no other community has to suffer from the detrimental long-term effects caused by these harmful facilities.”

What are the Alternatives?

Most agree that burning trash, while perhaps in some ways is better than alternatives like landfilling, is still not an ideal long-term solution. But what are the alternatives?

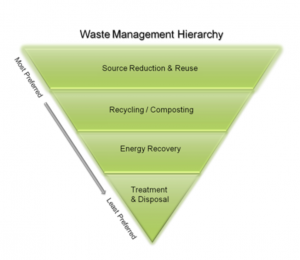

The US EPA has published a “Waste Management Hierarchy” – an inverted pyramid that’s sort of a ‘Maslov’s Hierarchy of Trash’. At the top (“Most Desirable”), the largest area is SOURCE REDUCTION (effectively, “stop producing things destined to become garbage”) – suggesting that we need a fundamental shift in thinking to solve our waste problem. Next is RECYCLING. Squarely in the middle is ENERGY RECOVERY – which is Wheelabrator’s model. Then TREATMENT – per the EPA “Prior to disposal, treatment can help reduce the volume and toxicity of waste.Treatments can be physical (e.g., shredding), chemical (e.g., incineration), and biological (e.g., anaerobic digester)” and finally (least amount, least desirable), DISPOSAL, which the EPA says usually means putting the remaining waste in “well-engineered, monitored” landfills.

Westchester County has made progress in moving some of its waste up the pyramid to source reduction and recycling over the last thirty years. In 1987, the Peekskill Resco plant (as it was called at the time) took in 501,581 tons of trash from the 36 communities in the county refuse district. In the last few years, that total has been reduced by about 25%, while the percentage of county waste that gets recycled has eclipsed 50% of the county’s total waste stream.

Westchester County has made progress in moving some of its waste up the pyramid to source reduction and recycling over the last thirty years. In 1987, the Peekskill Resco plant (as it was called at the time) took in 501,581 tons of trash from the 36 communities in the county refuse district. In the last few years, that total has been reduced by about 25%, while the percentage of county waste that gets recycled has eclipsed 50% of the county’s total waste stream.

Bury or Burn?

Wheelabrator believes waste-to-energy is still the best available option, telling the Herald,

“The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under multiple administrations has made clear in its waste hierarchy that converting waste to energy is preferable to landfilling. Waste to energy reduces greenhouse gases by approximately one ton for every three tons of waste processed versus landfilling. At the same time, waste to energy produces baseload, renewable electricity while offsetting the need from energy from fossil fuel sources such as oil, coal and natural gas. In addition to the U.S. EPA, numerous international governments, NGOs and researchers recognize the climate benefits of waste to energy, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Economic Forum, the European Union, CalRecycle, the Center for American Progress and Third Way.”

Indeed, most landfills are significant sources of greenhouse gases. Landfills account for 11% of global methane emissions, and US landfills give off nearly three times more methane (143 million tons in 2010) than the second-worst offender, China. US landfills release a similar amount of CO2 each year as well.

According to the IPCC, methane is 28 times as potent as CO2 when it comes to warming the planet over a hundred-year window – and 84 times more powerful when considered over twenty years (methane dissipates after a dozen years or so). So capturing methane from landfills is critical – so much so that the EPA requires operators of very large municipal solid waste facilities to capture their so-called “landfill gasses”.

The former Croton Point Landfill – which Wheelabrator Westchester’s operation effectively replaced – was capturing a million cubic feet of methane per day when it was capped in the mid 1990s. A pilot project to convert the gas to electricity and fuel for park vehicles was apparently scrapped in 1997; today the methane is “flared” or burned off to remove most of the VOCs.

But the methane capture program at Staten Island’s Fresh Kills landfill (now Freshkills Park) produces 1.5 million cubic feet of natural gas per day, which is sold by NYC to National Grid, and used by Staten Island residents for cooking and heating.

A perhaps less easily-solved problem with landfills is leachate, or water that’s percolated through the buried waste, often picking up pollutants and toxins along the way. “Modern, well-engineered” landfills (as the industry often refers to them), have a composite liner of clay and plastic membrane beneath them to reduce the flow of leachate into nearby ground water. But the EPA admitted in 1988 that “even the best liner and leachate collection system will ultimately fail due to natural deterioration.” Those liners are the main reason retired landfills are seldom covered with trees: the risk of deep roots penetrating the protective liners and causing leachate leaks is too grea

Other arguments in favor of incinerating solid waste versus landfilling are less technical: landfills devour huge areas of open space, often in relatively unspoiled, remote areas where land is cheap and population density is low. Incineration reduces the volume of trash by 90% or more versus straight landfilling, reducing the acreage needed. And as more and more urban and suburban landfills reach capacity or are closed due to environmental regulations (or political will), municipal waste often has to be trucked for hundreds of miles from its urban sources. This often adds more trucks to both interstate highways and rural routes, increasing our carbon footprint while degrading our physical environment.

Low-Hanging Fruit

According to a 2020 county-commissioned study, “It is estimated that Westchester County disposes approximately 103,000 and 85,000 tons of food waste per year from the commercial and residential sector, respectively. The combined amount of 188,000 ton/year represents the total food waste that is potentially available for processing and recycling in the County.” Food waste is a unique portion of the solid waste stream, because it can be composted or anaerobically digested to break it down, reduce its volume, and create valuable, natural fertilizer. That makes it low-hanging fruit in the effort to reduce the amount of waste being incinerated at Wheelabrator.

In December, Westchester County Executive George Latimer broke ground on “CompostEd” – a “small-scale food scrap composting demonstration and education site” in Valhalla. CompostEd is designed to promote composting and food scrap recycling by county residents. Meanwhile, in January the county completed a comprehensive study for a proposed county-wide food waste recycling program. The study looked at a range of options for collecting, transporting, and “digesting” residential food waste in enclosed anaerobic digesters located within the county.

The report has some elements that are strikingly reminiscent of the 1970s saga that began with a court order to close the county’s Croton Point Dump – and ended with the opening of Peekskill’s Wheelabrator plant. In 2019, New York State passed the Food Donation and Food Scraps Recycling Act mandating that by January 1, 2022, virtually all businesses that generate an average two tons or more of wasted food per week must donate all edible excess food, and recycle the remainder “if they are within 25 miles of an organics recycler (composting facility, anaerobic digester, etc.)”

Among the report’s mid-term recommendations is a potential digester to be co-located at either the Wheelabrator plant or Westchester’s water treatment plant – both located in Peekskill. Either option would likely divert up to 10,000 tons of food waste from the Peekskill incinerator, in as soon as three years. Longer-term, the county plans to build a dedicated anaerobic digester, likely “through a public-private partnership,” – with a likely location near the Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla. The dedicated digester facility could eventually handle up to 80,000 tons of food waste per year.

A pilot program is already underway to test the viability of collecting and digesting residential food scraps in Westchester. Peekskill recently joined the county’s Intermunicipal Agreement allowing the city to take part in the county’s Residential Food Scrap Transportation and Disposal program. The Conservation Advisory Council is working with the city to finalize the details, which would begin with one or more centralized drop-off locations, and could eventually include curbside pickup. In the meantime, Peekskill’s CAC is also cosponsoring a program with the Greenburgh Nature Center to offer discounted backyard composters to city residents.

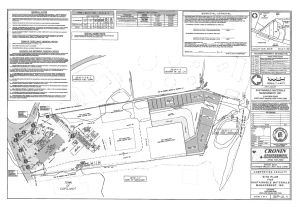

Separate from the county’s plans, CRP Sanitation has proposed to build a “source-separated organic composting” facility at 2 Bayview Road, just over the Peekskill city line on Roa Hook in Cortlandt. When complete, the facility will be able to receive up to 5,000 cubic yards of food waste per year, to be mixed with “tree debris”, i.e. shrubs, branches, trunks etc. collected by Cortlandt’s DPW. The mixture will be “anaerobically static-pile composted” to create mature compost for use as household fertilizer. Residents will be able to sign up to contribute food scraps, and in return receive a certain amount of compost for their own use.

How Else Can We Reduce Our Waste?

Even if every bit of food waste in Westchester county was anaerobically digested or composted, and every recyclable item were recycled, that would still leave several hundred tons of solid waste per year in need of disposal.

Groups like GAIA promote “Zero Waste”, a concept of dramatic overall waste reduction that focuses on “reducing consumption and discards”, reuse of products and raw materials, and “producer accountability”. Already, sellers of items like electronics and car tires often are required to account for the recycling of those items.

Others are concerned with making sure items can be repaired when they break. The “right to repair” movement aims to prevent product manufacturers from restricting consumers’ ability to fix things rather than toss them. When is the last time you had a home appliance or electronic device repaired? Consumer goods have become so inexpensive to purchase – and so difficult to repair – that we’ve gotten used to just putting them at the curb as soon as they stop working, and ordering a replacement from Amazon. The model of “planned obsolescence” is a major source of household waste these days.

Another significant part of today’s waste stream is textiles. The “fast fashion” trend of the past twenty years has caused a doubling of the amount of textiles we produce annually, from 9.5 million tons in 2000, to over 17 million tons by 2018. Over 66% of that amount was landfilled, representing 5.8% of US municipal solid waste that year. The same year, 3.2 million tons of textiles were incinerated at waste-to-energy facilities; only 2.5 million tons were recycled.

Aside from just purchasing higher-quality, longer-lasting clothing, consumers can donate used clothing to charities (though even Goodwill landfills around 11% of donations); sell or give unwanted items to second hand stores; or take last year’s fashions to any of a number of recycling collection points catalogued here by the New York State Association for Reduction, Reuse and Recycling (NYSAR).

What’s the Future of Wheelabrator Westchester?

In 2019, Westchester County renewed its agreement with Wheelabrator Industries to operate the Charles Point incinerator through 2029. As mentioned earlier in this piece, that would make Wheelabrator Westchester perhaps the oldest continuously-operating waste-to-energy plant in the US.

The Herald spoke to Peekskill Common Council member Dwight Douglas, who was Deputy Director of the city’s Planning and Development Department as the Resco plant opened in 1984. We asked him if he thought Wheelabrator would still be around at the end of this decade.

“I was a rookie housing specialist at the time the Resco agreement was done, but had moved up to deputy director by the time it opened, and the excess 45 acres or so were turned over to the city for redevelopment…now known as Charles Point Industrial Park,” said Douglas. “I worked extensively with my colleagues in the department in turning this land into commercial and industrial uses which generate jobs and taxes.”

“I am not up on the technology which would allow us to close the plant. There has been a lot of focus on recycling and composting and cutting down on waste, but that still leaves a stream of material to be disposed of and I have no idea how that might feasibly be accomplished with the plant gone. As long as the plant can’t be replaced, the focus should be on using the latest tech to clean the air as it is emitted up the stack.”

But other Peekskill residents aren’t so sure. “It’s an urgent situation – not only because our health is being harmed, but because the plant is 36 years old and most incinerators are retired after 23 years,” said Conservation Advisory Council member Courtney Williams. “This plant is unlikely to survive to complete its contract with the county, as it would be tied for the oldest incinerator in the nation if it does. I think we are at the beginning of a concerted, county-wide effort to get Wheelabrator shut down – and put in place the processes necessary to to deal properly with our waste stream.”

Next week’s Herald will follow Peekskill’s recyclables from the curb to their ultimate destinations.