Part one of a two-part look at Wheelabrator Westchester’s waste-to-energy plant in Peekskill; how the county currently deals with solid waste; and what are the costs, benefits and potential alternatives to the current system.

As I write these words on a Monday morning in April, I’m serenaded by the familiar sounds of a Peekskill DPW “packer” truck and its crew. Air brakes squeal as it stops in front of our home, followed quickly by the sound of a plastic trash can lid skittering on the sidewalk. The unintelligible shout of a DPW sanitation worker directing the driver; the hollow thunk of our empty can hitting the pavement, then the roar of the Mack diesel engine straining against the truck’s weight as the packer rumbles up the slight grade to our neighbor’s house, where the stanza repeats.

This Monday morning symphony is the weekly culmination of a daily routine: we collect our used kleenexes, browning bananas, coffee filters heavy with wet grounds, bags of dog poop, that sock with the hole in its heel – everything we want out of our lives for good (minus that sizeable pile of junk mail, milk cartons, wine bottles, and other things we perceive to be recyclable). These cast-offs spend a few days in the circular file or perhaps in a kitchen step can, eventually filling large plastic trash bags – which in turn fill even larger plastic trash barrels. On Sunday or Monday evening (depending on whether you’re a Peekskill westsider or eastsider), we dutifully drag those Rubbermaid cans (no larger than 35 gallons!) to the curb, say a little prayer that it’s neither a city holiday nor will a raccoon target our trash overnight; and in return, the Magical Waste Fairy (aka Peekskill’s Sanitation Department) will visit us in the wee hours and take our unwanted (and besides that smell, already forgotten) garbage to another dimension.

And yet, for as much as we take this routine for granted, do we ever stop to ponder exactly where our garbage goes when it leaves our human plane every week? Do we dig a hole and give it a proper burial, like we used to? The short answer is ‘no’. In most of Westchester County, we now cremate it – and the crematorium for our solid waste is right here in Peekskill.

The longer answer is surprisingly close, yet rarely considered. Peekskill, like thirty five other Westchester municipalities, sends all of its non-recyclable solid waste to the Wheelabrator Westchester waste-to-energry plant (officially called the “Charles Point Resource Recovery Facility”) at the foot of Louisa Street. The ten-story mustard-colored incinerator at Charles Point is a ubiquitous sight for Peekskill residents. Depending on the weather, its 195 foot smoke stack emits a massive white steam cloud that can sometimes be seen from downtown. It’s the northernmost of a trio of massive, steam-belching industrial landmarks that punctuate the Hudson River shoreline including LaFarge Gypsum in Verplanck, and the Indian Point nuclear power plant in Buchanan.

Solid waste from the 36 municipalities comprising Westchester’s Refuse Disposal District #1 comprises only about half the garbage burned at Wheelabrator. Trash from private carters makes up the rest.

From all Corners of Westchester

For Peekskill residents, the funeral procession for their unwanted possessions is surprisingly brief: our packer trucks drive straight to the Wheelabrator plant when they’re full. But let’s zoom out and look at the whole county to understand the entire system.

For many of the 36 municipalities in Westchester’s Refuse Disposal District #1 (about 90% of the county’s population), their trash’s trip from curbside pickup to Wheelabrator is slightly more complicated. In order to reduce the total number of municipal waste trucks making daily trips to Peekskill, the county built three transfer stations: one in White Plains, another in Mount Vernon, and a third in Yonkers. Trash from cities, towns and villages in the southern half of Westchester gets “tipped” from the packer trucks inside these facilities; it’s then compacted into 75 cubic yard municipal waste trailers (packer trucks are typically 25 – 30 cubic yards and compact at a 6:1 ratio), which make their way to Peekskill. You’ve likely seen the cobalt blue tractor trailers, many of which travel Route 9, exiting onto Louisa Street and heading a half mile west, directly to Wheelabrator’s driveway at 3 John Walsh Boulevard.

Inside the Gates

Wheelabrator Westchester accepts solid waste deliveries from 4 am to 6 pm Monday through Friday, and 4 am to Noon on Saturday. Given the schedule of typical municipal waste pickups, the busiest delivery times are Monday, Tuesday, and Friday mornings. Arriving trucks check in at the main gate, visible from the entrance of Charles Point Park, then proceed up a winding driveway designed to accommodate a long line of waiting vehicles if necessary. The driveway runs uphill, disappearing into a forest of mature trees, which minimizes one’s awareness of the operations beyond. The plant sits on the edge of a tall bluff overlooking the Hudson River.

A year ago, the final leg of Peekskill’s Riverfront Trail was completed; the new trail segment connecting Fleischmann Pier to Lent’s Cove winds its way along the shoreline of Charles Point, snaking behind Wheelabrator; after 37 years, it provides Peekskill residents their first up-close glimpse of the plant’s operations (at least what can be seen above its seven foot screened fence).

A bit of Wheelabrator trivia: just beyond the plant’s visitor parking lot is a 30 x 30 foot concrete pad called 2NK4 – one of only a dozen FAA-registered heliports in Westchester County.

The first stop for solid waste trucks at Wheelabrator is a scale. The total weight of the truck plus its contents is recorded; the empty truck will be weighed again before leaving, to calculate the total tonnage – and thus the charge to the hauler (referred to as a “tipping fee”).

Once weighed, the trucks continue uphill, driving into what’s referred to as a “reception area” (which one assumes has never hosted a wedding). The reception area is a massive open hall, roughly 50 feet high and enclosing about 25,000 square feet. Garbage trucks and waste haulers drive into the building, disgorge their sordid contents, and drive out the other end to a second scale, then back down the winding driveway to exit.

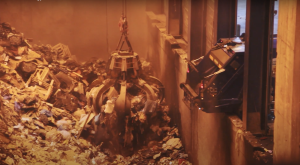

Most trucks back into loading docks overlooking the second room, but occasionally plant personnel will have a truck empty onto the reception floor so its load can be inspected for prohibited items like car batteries, hazardous waste, or concrete. The second room contains a cavernous pit called the “fuel bunker”, which is half again as long – and many times deeper – than an Olympic swimming pool.

Overhead, a pair of yellow gantry cranes roll back and forth on an enormous track. Each has a giant claw suspended from cables, which an operator maneuvers and drops down into the pile of trash, closing the grip and grabbing a ton of trash at a time. With the waste in its grasp, the operator raises the claw while it rolls forward across the bunker, releasing the grip once it reaches a large opening near the back wall, allowing the material to drop into a large hopper. The process is shockingly similar to the infamous “claw” arcade game, except this claw ain’t playin’ – and in this case no one’s even pretending that the prize isn’t pure garbage.

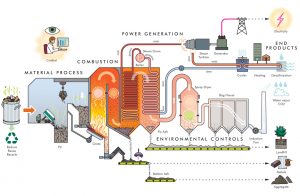

Once in the hopper, hydraulic rams push the solid waste into a Babcock & Wilcox “integrated waste fuel boiler unit”. Each of the three “water wall” boilers has a set of sloping, reciprocating metal grates, like a giant barbecue grill that’s in constant motion to ensure the trash is completely burned. The plant’s Von Roll grates, originally developed in Europe, had to be redesigned for American garbage – which has a higher content of plastics, resulting in hotter burn temperatures.

The goal is to keep the trash moving and aerated so the material can reach 2,500º F, breaking down into smaller and smaller bits that eventually fall through the grates to the floor of the burners as “bottom ash”. The volume of this ash is only 10% of the waste that produced it. A Wheelabrator video says the plant “continually draws air from the waste storage areas into the boiler, creating a constant negative pressure that prevents the escape of dust and odors.”

The superheated combustion gases from this garbage barbecue flows upward past a zigzag of water pipes,  heating the water and producing high-pressure steam (much like a car’s radiator). According to the original installer, the boilers produce 170,000 pounds per hour of 900 psi steam. The steam is piped to the generator room, where it drives Wheelabrator’s Brown Boveri steam turbine generator, capable of producing 60 million watts of what the company describes as “clean, renewable” electricity.

heating the water and producing high-pressure steam (much like a car’s radiator). According to the original installer, the boilers produce 170,000 pounds per hour of 900 psi steam. The steam is piped to the generator room, where it drives Wheelabrator’s Brown Boveri steam turbine generator, capable of producing 60 million watts of what the company describes as “clean, renewable” electricity.

Depending on who’s explaining it, that’s enough to power somewhere between 39,000 and 67,000 homes. Since 2013, a portion of the plant’s steam is routed through an insulated pipe running beneath John Walsh Boulevard to the White Plains Linen plant across the street. The hospitality linen service buys the steam from Wheelabrator, and uses it in place of natural gas to run their industrial sized laundry; the company says it saves money while at the same time avoiding the use of fossil fuels.

Compared to the massive steel derricks that carry nearby Indian Point’s 2 billion watts out to the grid, the output of Wheelabrator’s 60 megawatt power plant is visually underwhelming. The high voltage power lines snaking out from behind local entertainment complex Factoria, connecting Wheelabrator to the small substation a mile down John Walsh Boulevard – almost blend in with the conventional lines that service the nearby industrial parks.

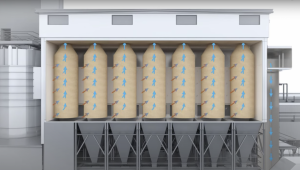

Back at Wheelabrator’s three boilers, the hot exhaust gases (filled with toxic “fly ash”) are passing through a gauntlet of treatments designed to clean the vapors before they’re released through the plant’s chimney. According to the Wheelabrator animation:

- A “selective noncatalytic reduction system injects a urea mix…to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions”

- “Powdered activated carbon is injected to capture mercury and trace organic compounds”

- “The flue gas then enters a spray dryer absorber, or dry scrubber, where lime is combined with the gas, to neutralize acid gases – including sulfur dioxide and hydrogen chloride”

- “The flue gas then passes through a fabric filter, or electrostatic precipitator, where particulates including fly ash, lime, carbon containing mercury and organics, and any remaining pollutants are removed.” This is my favorite part of the animation: the filters look like 50 foot tall paint rollers, and I wonder how often they change them.

- “The cleaned flue gas exits through the stack after a series of continuous emissions monitors analyze and record emissions levels.”

Meanwhile, at the bottom of the three boilers, the bottom ash passes through separators that extract ferrous metals like iron and steel, which are sent to recyclers. The remaining ash is loaded in hopper-type trailers and trucked to Wheelabrator’s ash “monofill” in Putnam, Connecticut; a 150 mile trip on I-84 to the northeast corner of the Nutmeg state. According to Wheelabrator, nonferrous metals like aluminum and copper are removed at the Putnam site for recycling, before the remaining ash is buried there.

Except for maintenance shutdowns, the fires in the three boilers are kept burning around the clock, every day. According to a 2014 Wheelabrator traffic analysis, the plant stockpiles extra trash at the end of each week to ensure there’s enough fuel to make it through the weekend.

Wheelabrator Westchester – By the Numbers

In 2021, the total “tipping fee” charged by Wheelabrator to the 36 municipalities in its “Refuse Disposal District #1” (RDD) to drop off waste at the Peekskill facility is $80.49 per ton. Of that total, each local community contributes $29.83 per ton, and Westchester County subsidizes the remaining $50.66 per ton.

In 2020 the Charles Point plant received an estimated 370,000 tons of waste from District municipalities – up slightly from 2019, which the county attributed to people working from home during the pandemic. Private carters and municipalities outside Westchester’s RDD brought another 336,400 tons, for a total input of 706,400 tons – or 99.5% of the plant’s permitted 710,000 ton capacity. According to Wheelabrator the plant also takes in waste from New York City, Putnam and Dutchess Counties via private contracts.

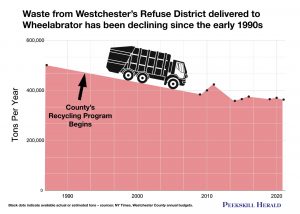

Westchester County appears to have hit “Peak Trash” in the late 1980s before the county officially began recycling in 1992. In 1987 the RDD brought just over 500,000 tons of municipal waste to Wheelabrator. With recycling, by 2009 that number had dropped to 384,000 annual tons, but was projected to increase to over 400,000 tons in 2012. In 2013, the district’s share of solid waste brought to Charles Point had fallen to 352,642 tons, and in recent years has plateaued at around 360 – 370,000 annual tons, as household recycling in Westchester increased to account for 52% of the county’s solid waste stream.

According to the city’s website, Peekskill DPW collects around 13,125 tons of trash each year; that’s about 3.5% of the District’s total solid waste in 2020. The city represents around 2.8% of the district’s population, meaning Peekskill residents throw out about 20% more per capita than the average District member. That’s likely a corollary of Peekskill’s lower-than-average recycling rate, which is only around 24% of all disposed waste.

Incinerating that much trash costs the county and its RDD-municipalities some $30 million per year – which is collected by each community as part of its residential and commercial property taxes.

If you’re a property owner in Peekskill, that charge appears on your City/County tax bill as “County Solid Waste”. A quick look at a recent bill shows the total collected by the city in the second half of 2020 was $569,433 – a jump of 9.1% over 2019. The average Peekskill property owner paid about $177 to the county for waste disposal last year (the actual amount is a function of each property’s assessed value).

New Name, Same Game

Last week, Wheelabrator announced the acquisition of nine other companies in the waste collection, transportation and disposal industries, which will collectively be rebranded “WIN Waste Innovations”. The Charles Point plant will get a new name for the first time since it officially dropped the RESCO moniker. And it signals that the parent company, Wheelabrator Technologies, is doubling down on the idea that dealing with solid waste is a need (and a business) that’s not going away any time soon.

In Part Two (which will post Saturday morning), we’ll look at the costs, benefits and potential alternatives to Wheelabrator’s Peekskill operation.

This post was updated on 4/20/21 to correct the tipping fee amounts charged to Westchester County and the member communities of its Refuse Disposal District #1.