In Part One of this feature on the likely impact of new residential development on Peekskill’s infrastructure, we looked at so-called “hard infrastructure” – the nuts and bolts systems like water, sewer, streets, sidewalks and parking – that comprise much of the physical fabric of our city. Today, we take a look at the less structural – yet equally important elements we’ll collectively call “City Services & Schools”.

SCHOOLS

You likely already know from our recent reporting that Peekskill City Schools, while currently in the midst of several years’ worth of dramatic improvements in student achievement, are underfunded and challenged in a number of ways relative to most other Westchester school districts. Will the likely influx of additional students over the next few years increase stresses on an already strained system?

The district has already been growing at a significant pace, with enrollment up roughly 20% since 2006, according to PCSD Assistant Superintendent for Business Robin Zimmerman. Based on the rate of increase over the last five years, the district expects to see another 5% increase by 2025. A January, 2020 Journal News article stated that from 2008 – 2018 Peekskill was the second-fastest growing Westchester district, trailing only Port Chester in that time period.

At the outset of this exploration, we detailed our methodology, arriving at an estimated 159 additional public school students – if all the roughly 1,500 proposed/in-progress new dwelling units are completed by 2025. That would equate to a 4.5% increase over 2021 enrollment, or 12.2 additional students per grade level – roughly on par with the district’s own estimates.

Peekskill schools receive roughly 46% of their funding from New York State; 3% from the federal government; and the remaining is generated locally. State and federal aid is generally calculated on a per-student basis, and therefore scales up with an influx of new students. But given the financial chaos caused by the COVID pandemic, both revenue sources are likely to face cuts in the near term.

Local school funding (roughly 43% of all sources) comes via a tax levied on all property owners, regardless of whether they have children in the public schools. The tax is based on assessed property values – and the rate is adjusted annually to deliver enough revenue to balance the voter-approved school budget. Peekskill’s 2020-2021 school budget is $98.5 million. For some perspective, the overall city budget is just over $60 million.

As of 2019, Peekskill schools had an average 15.5 students per teacher – a bit lower than the US average of 16 to 1, and a fair amount higher than the New York State average of 12.2:1 students for each instructor.

On the physical infrastructure side, we looked at the stated operating capacity of Peekskill’s six school buildings, as shown in a December, 2018 Capital Projects report. Based on current enrollment, and our projected increases of 12.2 students per grade level, we believe four of the six school buildings – Woodside, Oakside, Hillcrest, and Peekskill Middle School – will be operating just slightly over capacity, at 102 -103% – by 2025. Uriah Hill gained some additional classroom space for its pre-K program in 2020 when the district moved the Family Resource Center to a former fire hall on South Division, and the High School will gain 10,000 square feet of learning space when the new STEAM lab opens this fall; both moves should help offset the influx of additional students.

Beyond the additional capacity created by those capital projects, “there is a natural migration of student movement; new students move in and other students move out,” notes Zimmerman, “creating stable enrollment in the long term.”

Likely impact of new residential development on SCHOOLS: LOW

While the likely influx of 500+ new students over the next four years represents a substantial increase of 15% to 20% over current enrollment, the additional education costs (at least theoretically) will be offset by additional federal and state aid, as well as increasing revenue from the expanding tax base as new real estate is assessed and additional taxes are levied.

The additional students could have a significant impact if it is determined that existing school buildings need to be expanded or additional schools built. What seems likelier is that the existing schools will operate at or slightly above intended capacity for some time.

EMERGENCY SERVICES

Police Department

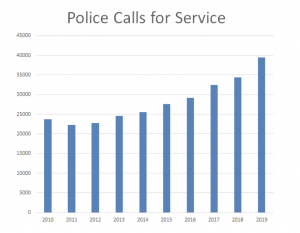

According to the Police Reform Task Force Draft Recommendations released in early February, the Peekskill Police Department responded to 23,690 total calls for service in 2010, when the city’s total population was 23,583. Following a slight dip in 2011, the number of calls has risen annually to a high of 40,750 in 2020 – an increase of 72% in ten years. In the same time period, Peekskill’s estimated population has grown by 500 – 1,000 residents – an increase of 2 to 4%.

In the same time period, the Police Department’s head count has shrunk by nine officers and four civilians – from 74 to 61 employees (51 officers and 10 civilian staff) – a personnel reduction of around 18%. It’s important to note that six of the nine fewer officer positions are funded, but currently unfilled, due to hiring delays caused by several civil service policies. Per the same draft report, the annual Police Department budget (currently at $8.8 million, or 21% of the city’s General Fund) has remained relatively flat over the decade, largely due to the reduction in staff.

Will an additional 3,000 residents result in an exponential growth in police calls over the next several years? A 2003 US Department of Justice study of US police agencies found the typical officer-to-civilian ratio in municipalities of 10,000 – 24,999 residents was 2.0 officers per 1,000 population. At 25,000 – 49,999 the ratio falls slightly to 1.8 per 1,000 residents. Even with a projected population gain of 3,000 residents by 2025, Peekskill’s current funded officer count of 57 officers would put the officer-to-civilian ratio at 2.1 per 1,000 residents – or slightly better than the US average.

In the meantime, the PD’s Capital Plan calls for investing $985,000 in new assets and equipment over the next five years – including $610,000 for new vehicles, and $175,000 to upgrade the police radio communications system. Note that all new vehicle purchases (across all city departments) have been deferred until 2022 due to budget stresses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fire Department

Peekskill’s Fire Department is considered a “combination” department – staffed by 24 salaried professional firefighters, and 75 volunteers. Much of the department leadership (Fire Chief, Assistant Chiefs, Captains etc) come from within the volunteer ranks.

The Fire Department’s annual budget for 2021 is $3,865,908, or just over 9% of the city’s General Fund. This is an increase of 12% over the 2018 actual spend. The increase comes on the heels of a projected 2020 shortfall of $458,000 – largely thanks to “extraordinary overtime costs in the Fire Department driven by the need to adopt a new Covid-safe staffing schedule”, according to the 2021 Budget Summary.

According to its website, the Fire Department answered 745 calls in 2020, averaging 62 per month. Per an independent review proposal from November, volunteers perform an “essential support role” in the department, yet their participation rate is declining even as Peekskill’s population is increasing.

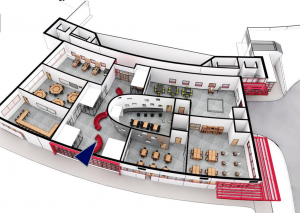

In 2018, the city consolidated five individual fire companies, each housed in separate, aging and difficult to upgrade facilities, into the new state-of-the-art Central Fire Station at Main and Broad Streets, pictured above.

In 2018, the city consolidated five individual fire companies, each housed in separate, aging and difficult to upgrade facilities, into the new state-of-the-art Central Fire Station at Main and Broad Streets, pictured above.

A 2018 profile of US fire departments by the National Fire Protection Bureau (NFPA) found that the median number of career firefighters serving cities of 25,000 residents was 1.2 per 1,000 population, and 0.96 volunteers per 1,000 civilians. Peekskill’s current department makeup puts us around 18% below the US median career firefighters-per-resident for small cities – but almost triple the rate of volunteers. With an additional 3,000 residents, our existing 24 paid firefighters would be 27% below the median for similar-sized cities; if we kept 75 volunteers in 2025 we would still be well ahead of most small cities, and our combined career + volunteer firefighters count would still be higher than typical for our population.

Note that most communities of 25,000 or less tend to have all-volunteer companies, and above 25,000 tend toward professional fire departments, so Peekskill is right on the cusp.

The Fire Department’s Five Year Capital Plan projects spending $2,380,000 to replace a ladder truck, two engines, and a utility vehicle over the next five years.

Ambulances / Paramedics / EMTs

The Peekskill Community Volunteer Ambulance Corps has around 60 active members and responds to most medical emergency calls within the city. The Fire Department provides basic support when the Ambulance Corps is unavailable. Of Peekskill’s 24 career firefighters, two are certified as paramedics, and the remaining 22 are EMTs.

Per the SOLO project’s 2020 SEQRA filing: “Advanced Life Support responses are part of the Cortlandt Regional Paramedic Program which responds to approximately 5,000 calls in Peekskill and Cortlandt combined. Emergency medical call volumes have been growing between nine and ten percent per year for the past several years.”

Likely impact of new residential development on EMERGENCY SERVICES: UNCERTAIN

As Peekskill’s population continues to grow, it’s logical to expect a continued increase in police, fire and medical rescue calls. Expect to see budget increases over time for all three services.

With a brand-new Central Fire Station, if the Fire Department’s Capital Plan for replacing equipment is realized, that service should be well-positioned with physical infrastructure for some time – but needs to address the decline in volunteer participation, perhaps by increasing the number of paid professional firefighters.

In general, new residential buildings (with mandated modern fire detection and suppression systems) should be proportionally less of a burden on the Fire Department than older housing and building stock. But as we saw with 2019’s three alarm fire that destroyed the under-construction apartment building at 1847 Crompond Road – there’s no guarantees.

The Police Department, currently short-staffed compared to a decade ago and facing a raft of reform proposals, will likely feel a larger impact from residential development – not only from additional residents, but also from having more streets, parking lots and corridors to patrol.

TRASH, RECYCLING, AND PUBLIC WORKS

Besides maintenance of public infrastructure like streets, sidewalks, water and sewer (all of which we discussed in the first part of this article), Peekskill’s Department of Public Works also performs a number of other essential services such as waste and recycling collection, snow and leaf removal, and parks maintenance. The DPW is basically the jack-of-all-trades when it comes to Peekskill’s shared assets.

The DPW collects 13,125 tons of refuse yearly, depositing it (alongside most of Westchester County’s municipalities) at the Wheelabrator waste-to-energy facility on the city’s waterfront. The department also collects 4,100 tons of recyclables annually, which are trucked to a Material Recovery Facility (MRF) in Yonkers.

As part of the plan to develop multifamily housing along Lower South Street, the city has proposed relocating the existing DPW vehicle storage and maintenance facilities from Louisa and Lower South Streets, to a city-owned lot on Corporate Drive, near the shore of Annsville Creek. While still being studied, that infrastructure project has been earmarked in the city’s Capital Plan for $10 million over the next three years.

Other DPW-related planned capital investments include new garbage trucks, dump trucks, snow plows, and a potential $1 million renovation for the Depew Park Pool pump house.

Virtually every new multifamily residential development in Peekskill must either provide additional public recreation space onsite – or pay a per-unit fee into a city Parks and Recreation fund that’s designated to create additional park or recreation space somewhere in the city. Intended to ensure public recreation space grows to accommodate new population, the additional spaces and facilities are generally maintained by the DPW.

Likely impact of new residential development on PUBLIC WORKS: MODERATE

The proposed relocation of DPW facilities to allow mixed-use residential and commercial development along Lower South Street (SOLO project) is likely to be the single largest Peekskill public infrastructure project in the next half decade. Beyond that, additional residents will produce more trash and recycling, and expanded parks and recreation facilities will all combine to increase the DPW’s workload, and create a demand for additional equipment and personnel.

CONCLUSION

As we’ve seen, the City of Peekskill is a complex system of interconnected infrastructure; like a living organism, each system is staffed and maintained and “nourished” with funding. But – also like a living thing – these systems and their funding streams are often intertwined, codependent, and with few exceptions – sharing common resources.

From the look of things at this moment, it appears Peekskill is on relatively solid footing, in regard to both finance and infrastructure – well-positioned to welcome another 1,500 families over the next four or five years. But maintaining existing infrastructure – and upgrading it for the future – requires keen foresight, sharp planning skills, and lots of smart decisions made years ahead of actual needs.

One consideration as the city plans for its future, is whether revenues will grow at a rate necessary to keep pace with infrastructure demands. An area to watch closely is whether new residential developments are taxed at a rate comparable to existing residential buildings. The standard assessed tax rates are meant to ensure that there’s a dependable revenue stream that’s adequate to support the infrastructure and city services required by residents and businesses.

Often, when development projects are targeted to lower-income residents, developers are given tax abatements to allow them to provide affordable rents. That can create a discrepancy between the number of new residents and the amount of revenue brought in to fund the services provided by the city. As an example, ten all-affordable Peekskill housing complexes: Barham House, Peekskill Plaza, Stuhr Gardens, Wesley Hall, and the six Peekskill Housing Authority properties, collectively pay more than $2.9 million less property taxes annually than they would as market-rate rental buildings – that’s over 16% of the total property taxes collected annually by the city.

Does that mean Peekskill should stop developing new affordable housing? Certainly not – the need is too great – and according to city officials the affordability requirement being considered in the proposed affordable housing ordinance will have little impact on tax revenues. But the city needs to take a balanced approach to development – while pursuing all available revenue sources including state and federal grants – to ensure there’s enough overall income to provide and maintain the infrastructure needed to serve all of its residents for generations to come.

Categories:

Peekskill’s Infrastructure: Can It Handle Looming Population Growth?

March 6, 2021

More to Discover