This is part one of a two-part story about Peekskill’s infrastructure and how the coming residential development is likely to impact it. Part two runs on Saturday.

By Jim Striebich Infrastructure. It’s a word that’s been in the news a lot lately: we watched in horror as the Texas electricity grid failed during an unprecedented winter storm in mid-February, leading to a cascade of other infrastructure problems, including blackouts, frozen pipes, and the loss of running water for millions of Texans.

In Peekskill, “infrastructure” was featured in not one but two separate agenda items during the February 16th Common Council work session: first, newly-appointed Comptroller Matt Alexander presented the city’s five-year Capital Infrastructure Plan. Later in the same meeting, a resolution was presented, with the Council calling upon Congress to create “a National Infrastructure Bank to finance urgently needed infrastructure projects and to diligently pursue a matching program of direct federal infrastructure grant funds”.

Nearly every time we publish a piece about new development in Peekskill, the type of comments we receive are “Great, but where will the kids go to school?” “Will there be enough water pressure?” and “Our police and fire departments are already overworked!” Just this week, we saw a comment on an Instagram thread about “Peekskill Problems” saying “The downtown parking situation is terrible. And it’s only going to get worse as more people move here.” There appears to be much concern about whether Peekskill’s infrastructure can handle an influx of new residents – but little consolidated analysis or quantification done to determine if these concerns are truly valid.

What is Infrastructure?

Oxford defines infrastructure as “the basic physical and organizational structures and facilities (e.g. buildings, roads, power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise.” On the municipal level, infrastructure tends to refer to collective systems that serve the entire community, such as streets, sidewalks, the public water supply, the sewer system, the electrical grid, natural gas and other utilities, and city services like schools, sanitation, police, fire and EMS.

Within that matrix, residents of a town or city are often most concerned with the public assets and entities. Private utilities tend, on some level, to be self-preserving: if the natural gas network needs maintenance or upgrades, the utility charges customers a sufficiently high price for gas such that they can perform the maintenance or upgrades (though it’s worth noting that in much of Westchester County south of Peekskill, Con Edison has stopped approving new natural gas connections, blaming high demand and “constraints on interstate pipelines that bring natural gas to customers in Westchester County).

Public infrastructure like roads, bridges, dams, often water and sewer, and city services are subject to conflicting pressures such as residents demanding lower taxes; financial downturns; and local politics – which can often lead to deferred maintenance, neglect, mistaken priorities, and lack of long-term planning. Any or all of these are bad news for local infrastructure. And when a city’s population is on the rise, it can place higher demands on existing infrastructure, further compounding the situation.

Our Methodology

In the following paragraphs, the Herald looks at some of the major public infrastructure categories; their current conditions; how they are funded; and makes some educated guesses about how the coming wave of residential development is likely to impact each.

The following is not a professional analysis. It is merely an attempt to connect some dots and provide some perspective – using publicly-available information – to answer some of those frequent “but what about…?” development-versus-infrastructure questions mentioned above.

For the purposes of this exploration, we’ll assume that all the roughly 1,500 new housing units we looked at in our February 11th development piece actually get built over the next four years or so. We recognize that it’s likely some will take longer, others will be abandoned; but as we saw with the Broad-Howard proposal, others are likely waiting in the wings.

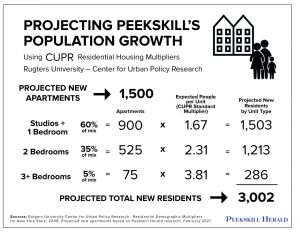

When it comes to estimating how many new Peekskillians all that new building translates to, most developers rely on “multipliers” to predict the number of residents per new apartment. A common resource is a 2006 Rutgers University study from their Center for Urban Policy Research (often referred to as “CUPR”). The CUPR multipliers derive from data taken from the 2000 US Census, and look at the makeup – broken down by age groups and other demographics – of typical US households. These data are further subdivided by the type of housing (single-family detached houses, 2 – 4 family, 5+ family buildings, rentals vs. owned units, and by home value or rent levels). Finally they’re specified by state, since typical household makeup tends to vary by different geographies.

At this point we have limited insight on specific breakdowns of unit sizes and costs for future developments. We know that Parkview’s proposed SOLO project on Lower South Street is composed entirely of one- and two-bedroom units, at roughly a 50/50 ratio. The initial phase of Magnolia Heights at 653 Central has proposed nine studios, 44 one-bedroom, and 25 two-bedroom apartments. One Park Place – projected to open early next year – will be 44 studios, 99 one-bedroom, 22 two-bedroom, and 16 three-bedroom rental apartments. And Fort Hill Apartments, which opened in 2018, is made up of 16 studios, 84 one-bedroom, and 78 two-bedroom units. If this trend continues, expect most of the upcoming rental inventory to be one- and two-bedroom apartments, likely weighted towards the 1BR variety.

For this article, we used the CUPR multipliers; assumed an average mix of 60% one-bedroom (including studios – CUPR considers studios to be one-bedroom apartments), 35% two-bedroom and just 5% 3+ bedroom units (CUPR has no category for studio); and that all newly-built units will rent at more than $1,000 per month ($1,100 for two-bedroom, $1,250 for 3BR units). Note that this category is the highest rental price bracket in the 2006 study and likely represents units priced significantly higher in 2021 dollars. We’re being conservative with our population estimates here; statistically, lower-priced apartments tend to house more people, especially children.

Using the above assumptions, if all 1,500 rental apartments come online by 2025, Peekskill will welcome approximately 3,002 new residents, of which 268 are school-aged children. Of those 268 new kids, per the CUPR averages, 194 are likely to attend public schools.

TRANSPORTATION

Streets & Sidewalks If you’re a walker, cyclist or driver (or some combination of the three) in Peekskill, you know that the roads and sidewalks here are a mixed bag. In general, streets are in decent shape, with some notable exceptions in the past few years, most memorably the temporary patching of street excavations by Con Edison following gas line upgrades in 2016 and 2017. After some delay, the utility eventually agreed to pay the city at least $338,000, allowing Peekskill DPW to properly resurface the affected roadways.

Each year, Peekskill repaves what it considers the roughest blocks. In late 2020 the city paid PCI Industries of Mount Vernon $669,300 to repave sections of Hadden Street, John Street, Nelson Avenue, Lakeview Drive, Howard Street, Park Street and Maple Avenue. Of that total, $505,716 was covered by New York State DOT funding; $25,000 was allocated from Peekskill’s Parks & Recreation fund; and the balance was covered by funds left over from the 2017 ConEd reimbursement.

When it comes to pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, the picture is somewhat less rosy: while most downtown sidewalks are serviceable, along outlying residential streets such as Decatur Ave and Chateau Rive on the north side, and Union Avenue and Depew Street near Depew Park, sidewalks are a patchwork, often ending at large rock outcroppings and not resuming beyond. With adjacent property owners responsible for maintaining them, existing sidewalks are sometimes treacherous where tree roots have upheaved bluestone; often strewn with litter in the summer, and snow-covered in winter.

Downtown, at any given time, a number of crosswalk signals are out of service, and a few busy crosswalks such as the west side of Division Street crossing Park Street southbound, confusingly have no signals at all. And there are currently no dedicated nor shared bike lanes in Peekskill. Even without the current uptick in residential development, Peekskill’s pedestrian infrastructure needs improvement. Several proposed DRI projects seek to address these issues, creating new pedestrian plazas, protected bike lanes, planting street trees, and adding street furniture like benches and bike racks.

In a major infrastructure improvement project, the City of Peekskill plans to rebuild nearly 1,200 feet of Oakwood Drive on the city’s north side this summer, reconstructing the roadway, sidewalks, and underground utilities including sewer, stormwater, and a hundred-year-old water line. The nearly $1.8 million project will be 80% funded by a federal grant, with the city covering the 20% balance.

Traffic

Automobile traffic isn’t a municipal infrastructure system. Like electrons flowing through a power grid, traffic is actually a consumer of our street system. But much like an infrastructure system, residential development and a rising city population will create impacts on traffic.

Transportation systems are especially complex because they are subject to the vagaries of human behavior – whereas water, electricity, and sewage are a bit more predictable. With vehicular traffic, changes in one neighborhood or even one intersection can have ripple effects in places across the city – or even in neighboring municipalities.

For this assessment, we were able to locate traffic projections provided in the Environmental Assessment Forms for two projects: the workforce-focused apartment building under construction at 645 Main Street; and the proposed SOLO residential/commercial development along Lower South Street. At 645 Main, the developer anticipates “30 additional trips” made by residents “in the AM peak hour and 36 trips in the PM peak hour.” Given that the parking garage empties onto Central Avenue, a broad, lightly-trafficked roadway, this building by itself would seem to have very limited impact on Peekskill’s traffic.

The SOLO project’s traffic analysis is much more detailed and complex, comprising six full pages. The study (which looks at traffic generated by both residential apartments and new commercial businesses) predicts 158 additional inbound trips and 179 trips outbound during the AM peak hour (if both phases of the development are completed); and 184 trips in / 191 trips out during the PM peak. That sounds like a lot, especially compared to 645 Main Street. But given the relatively robust existing street infrastructure – and relatively light existing traffic – around Lower South Street, Louisa Street and Route 9, the study concludes that “No capital improvements are suggested related to vehicular travel as a result of the SOLO development,” while recommending sidewalk improvements and general maintenance needed for Lower South Street.

“One challenge for a city or municipality experiencing growth is keeping track of vehicle trips over the course of time as multiple projects are considered and built and the roadway capacity (supply) is consumed (demand),” explained professional traffic engineer and Peekskill resident Frank Filiciotto. “One project’s traffic in year one becomes part of the background condition for a project being considered in, say, year five. Municipalities sometimes elect to examine potential development comprehensively to identify city-wide impacts and mitigation over the course of several years, getting ahead of it, so to speak. This way, new development can be accommodated with less uncertainty on either end.”

Filiciotto’s perspective on the challenge of planning for Peekskill’s growth is refreshingly positive and forward-thinking. “Unlike pipes that carry water, humans can choose how to interact with the transportation system. They can walk, ride a bicycle, hop on a train, drive a car, hail a taxi, take a scooter–or use some combination of modes. The key for any city, in my opinion, is to seek balance and equity in the system so that residents, business owners, and visitors alike have a favorable experience with the system regardless of their choice. This is a contextual challenge that requires forethought and creativity, but when done well it can improve safety and enhance quality of life.”

Parking

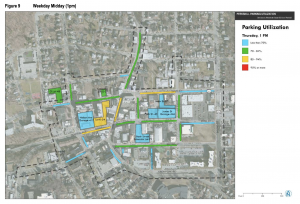

In 2017, the city commissioned a downtown parking study which looked at the 1,132 off-street parking spaces in downtown municipal parking lots and found that on average, 47% – 65% of spaces are unoccupied on weekdays, and 51% – 66% are unused at any given time on Saturdays. On-street spaces in downtown Peekskill typically peak at 70% capacity around 11 am weekdays, and are 76% occupied during the same peak on Saturdays.

Despite the ample availability even at peak times, the study did conclude that most drivers prefer on-street and surface parking lots over municipal garages, and that improvements to wayfinding signage as well as garage lighting and appearance could encourage more balanced usage. According to Peekskill’s 2019 State DRI application, the city invested over $4 million in infrastructure improvements such as LED lighting, wayfinding signage, structural improvements and electronic pay stations – but the application admits “more infrastructure work is needed”.

Parking is a significant revenue source for Peekskill, contributing almost $1.9 million to the city’s coffers in 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic ravaged city parking revenues as many city offices and businesses curtailed hours, or shuttered altogether beginning in late March, 2020. The initial 2021 city budget presentation on November 1st projected an overall decline in parking revenues of $600,000 for 2020. And in Comptroller Alexander’s February 16th budget update, he warned that the final number could be as much as $195,000 lower than originally predicted.

As the city recovers from the pandemic, increased residential development will likely drive some additional demand for downtown parking, but given that a significant percentage of the near-term building is happening in or near downtown, those new residents will likely walk to downtown businesses, and drive their cars to farther-flung locations. The new apartment building at One Park Place will have its own underground parking garage for residents; while the Broad-Howard development plans to lean heavily on underutilized parking in the city’s James Street Garage.

Impacts to Metro North commuter parking lots may be more significant – but this will also likely be offset somewhat by the drop in commuter rail usage and increase in remote working brought about by the pandemic.

The city recently installed two free-to-use ChargePoint electric vehicle charging stations: one at Riverfront Green and another next to the James Street Parking Garage. Expect to see increasing demand for public electric vehicle charging stations as sales of plug-in EVs have mushroomed in the past several years.

Commuter Rail

A year ago we likely would have been projecting sold-out commuter parking lots, crowded platforms, and squeezing into the dreaded middle seat when boarding city-bound Metro North trains at Peekskill in the next few years. But the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the commuter rail service. According to the MTA, weekday MNRR ridership is still down 80% or more, system-wide.

A recent spot-check of Peekskill’s commuter parking lots – permit-only reserved parking along Railroad Avenue and South Water Street – found lots that normally would be close to 100% full on a weekday afternoon were only 25 – 50% occupied prior to the afternoon rush hour. The loss of city revenue from annual permits not being renewed for 2021 is all but certain – but won’t be fully understood until some point later this year. The combined city income for the seven lots used primarily by rail commuters was over $192,000 in 2019.

Will ridership levels increase once COVID-19 is under control? Almost certainly. But there’s also a real likelihood that in post-pandemic times (and maybe sooner, given reduced-occupancy rules for offices and commercial spaces), many jobs that previously came with five-day-per-week commutes into Manhattan – will become hybrids of in-person and remote work, with employees taking the train to Grand Central two or three times per week instead of five – and Zooming in for remote meetings the other days.

It’s quite possible that Peekskill’s newest residents won’t all be packing the trains daily, as we once assumed, and that the overall impact on our rail service will be relatively minor.

Likely impact of new residential development on TRANSPORTATION: MODERATE.

Pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure is likely to be improved somewhat as the downtown population increases – new residents will demand safer walking and biking conditions. Traffic (both vehicular and pedestrian) is likely to increase along Central Avenue between Nelson Avenue and North Water Street as dozens of new apartments line the hillsides. Expect improvements for all transportation modes along Central Avenue and South Streets leading to the waterfront.

The SOLO project will increase car traffic along Lower South Street, and at the Route 9 interchange with Louisa Street. Congestion around the Peekskill train station is likely to increase during construction of proposed Railroad Avenue apartments, and corresponding street infrastructure improvements have already been proposed. But overall, Peekskill’s vehicular traffic is currently relatively light, and its street network and highway connections relatively robust – likely able to absorb a fair amount of additional traffic.

Downtown parking infrastructure is currently somewhat underutilized – with 1,500 additional homes you may have to look harder for a coveted on-street or surface lot parking space – but there will likely still be dozens of empty spaces in the municipal garages even at peak hours.

Ideally, most if not all of Peekskill’s future residential development will be pedestrian and public transit-focused, so that as the number of new residents increases, the number of vehicle trips accelerates at a gradually decreasing ratio .

WATER, SEWER and STORMWATER MANAGEMENT

The three components of the city’s hydraulic system – drinking water, sewage, and stormwater management – combine to account for nearly 16% of the city’s annual operating budget. In 2019, Peekskill commissioned a comprehensive engineering study of all three systems, providing a detailed, up-to-date look at these three areas of critical infrastructure.

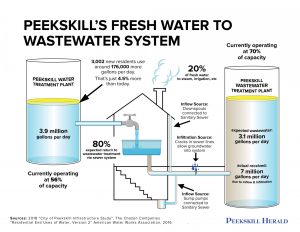

The City of Peekskill produces just over a billion gallons of drinking water per year, collecting water in two massive reservoirs in rural Putnam County, sending it to Peekskill via Peekskill Hollow Brook, purifying it at a modern plant in at the city’s north side – and delivering it to customers via three hilltop storage tanks, two underground storage wells, and 60 miles of water mains.

A 2018 study by Chazen Engineering found that the Hollowbrook Dam – a small reservoir and pump station in Cortlandt used to collect and pump raw water from the brook to the treatment plant – was in need of dredging and repairs. Those repairs were begun in 2019 and are ongoing.

The city Water Department is also in the process of replacing one of the three above-ground tanks on Benefield Road, and beginning to look at possible leaks in one or both of the underground storage wells. In the longer term, maintenance and upgrades to the two Wiccopee Dam structures in Putnam County will also be required.

Perhaps the biggest issue facing Peekskill’s clean water delivery is the 60 miles of water mains, 512 fire hydrants, and 653 gate valves. Most of these components were installed in the early 1900s. About half of the piping is cast iron, and much of it is tuberculated (constricted by interior corrosion). The 100-year old pipes also have a habit of breaking, and when they do, often the old gate valves are inoperable – sometimes unable to close to stop the flow, and sometimes unable to completely reopen after repairs are made. Much of the old piping itself is of smaller diameter than today’s standards.

The good news here, infrastructure wise, is that the heart of the operation – Peekskill’s Water Treatment Plant – is only ten years old, and as of 2018 it was operating at only 56% of capacity. It has a considerable lifespan remaining – and available capacity to provide more water as demand increases.

A 2016 American Water Works Association study estimated that the average American household resident uses 58.6 gallons of water per day. Returning to our CUPR numbers, if all 1,500 proposed apartments are built in Peekskill (containing 3,002 new residents), the overall daily consumption of purified water increases by just under 176,000 gallons – an increase of about 4.5% over current total daily demand. That still leaves Peekskill’s treatment plant with over 40% additional capacity for future development.

On the sewage side, the Peekskill Sanitary Sewer District (which includes parts of Cortlandt, Shrub Oak, Mohegan Lake, and Yorktown as well as the city itself), uses a network of 108 miles of pipes and culverts to convey 7 million gallons of wastewater per day to the Westchester County-operated Peekskill Wastewater Treatment plant, on the banks of Annsville Creek just north of Bear Mountain Parkway. The Treatment Plant is capable of handling up to 10 million gallons of wastewater per day – so it is currently operating at around 70% of capacity.

Residential wastewater is typically expected to be approximately 80% of fresh water demand – the water that goes back down the drain after use. The remaining 20% gets boiled away, sweated out, sprayed on lawns, etc. Returning to our 1,500 proposed new dwelling units consuming 176,000 gallons per day of clean water, with 80% of that amount (about 140,000 gallons per day) returning to the Peekskill Wastewater Treatment Plant – we barely move the needle vs. the plant’s total capacity, adding about 1.4% per day.

A much bigger issue for our wastewater treatment system than new development is something called “I&I” or inflow and infiltration. Inflow is wastewater conveyed to a sewer system from improper sources such as roof drains and sump pumps (which by law should be absorbed into the ground onsite). Infiltration refers to groundwater that seeps into the system via cracks in pipes and sewer mains. Both improper water sources can overwhelm a treatment plant.

In a 1995 assessment of Peekskill’s infrastructure, Sverdrup Corporation estimated that over 3 million gallons of wastewater arriving at the plant daily came from inflow and infiltration – fully 50% of the wastewater being treated every day. By 2018, Chazen Engineering estimated the inflow and infiltration had increased to 4 million gallons per day, and identified four areas of the city contributing nearly 90% of the I&I. Chazen said “the City should make improvements to these areas a very high priority.”

In the 2018 study recommendations, Chazen said “The City water and sanitary distribution and sanitary systems may be undersized or undersized from the event of new growth and development” and recommended that “The City perform capacity and flow analysis of both systems. As new projects are identified, the City will be in a position to understand potential impacts.”

A current example of this sort of planning: one of the larger capital expenditures projected in the 2021 city budget is the planned relocation of a sewer line beneath Lower South Street, in anticipation of Parkview’s SOLO development. The city is planning to allocate $3 million in matching funds in 2022, and expects to receive a $750,000 grant from the state’s Environmental Facilities Corporation. According to a January 2020 article in Westfair Online, “the idea is to make the line capable of handling the effluent from future development in the area.”

Likely impact of new residential development on WATER, SEWER and STORMWATER: LOW

Peekskill’s Water and Sewer systems are somewhat unique entities within the city, given that they each have their own dedicated funding stream (Water Fund and Sewer Fund). The Water Fund is sustained by revenues from the metered sale of water to residents and businesses. The Sewer Fund is collected from property owners as part of their property tax bills. So for each of them, as consumption increases, to some extent so do revenues. The addition of 1,500 new apartments will have a relatively insignificant impact on overall consumption, and both fresh water and sewage treatment plants have additional available capacity at this time.

In regard to stormwater, in general new developments must handle all stormwater runoff onsite, using permeable surfaces, dry wells, retention ponds and other methods – so theoretically the additional housing should cause minimal impact to the existing storm sewer system.

That said – over time, the three systems themselves require maintenance and upgrades – and with an expanding residential footprint – the need for additional infrastructure such as new water and sewer lines serving the new developments. While not insignificant investments, such projects are often subsidized by state grants, and can be financed and paid off over time via municipal bonds, reducing the overall impact to residents in any given year.

In the second part of this feature (coming Saturday morning), we’ll look at the likely impact of new residential development on some of Peekskill’s “soft” infrastructure – city services like trash and recycling collection, emergency services, and – though technically not a city service – the very crucial area of education and city schools.

Peekskill’s Infrastructure: Can It Handle Looming Population Growth?

March 4, 2021

More to Discover