This is the second of a two-part series on the issue of development and affordable housing in Peekskill.

By Jim Striebich

Within the affordable housing discussion, some point to Peekskill as an ongoing success story. Peekskill leads most other Westchester locales in both the number of existing and planned “affordable” housing units as defined by HUD. Documents prepared by Peekskill City Councilman Dwight Douglas and shared with the Council in July show that as of 2013, Peekskill led all other Westchester County municipalities, building more than twice the number of affordable units as set as a goal by the county in its 2000 – 2015 Affordable Housing Allocation Plan (325 units built or renovated by 2013 vs. a goal of 132 by 2015).

In the same review, Douglas estimated that Peekskill currently has 742 affordable dwelling units in the downtown, vs only 39 market rate. Among planned but not occupied projects, that ratio is reversed: 82 affordable units planned vs. 246 market rate (181 of those market rate apartments are in the middle of construction at One Park Place). But even with the large number of market-rate rentals coming online, that still means downtown will have more units defined as affordable than market rate – by a factor of nearly three-to-one. It’s worth noting that a significant percentage of the affordable units are in older buildings that are 100% age- and/or income-restricted.

Outside of downtown, from 2014 to 2020, Peekskill added 328 affordable apartments to 200 market-rate. “Peekskill actually builds residential developments that are 100% affordable,” notes Douglas. “Besides the many that exist here, there are two [affordable developments] currently under construction and one planned for Lower South Street. These projects all utilize a number of federal, state, and county programs which have their own criteria for compliance. If the other 42 Westchester County municipalities were to undertake what our city is doing, it’s conceivable that we would not have an affordable housing problem in the county.”

But affordability advocates such as Peekskill Equitable Housing Coalition argue that many of the HUD-defined “affordable” units are still well out-of-reach for many Peekskill residents.

In 2017, the federal judge in the Anti-Discrimination Center lawsuit assigned Stephen Robinson to monitor Westchester County’s compliance with the consent decree. In early October 2020, Robinson shared a draft with county officials, and according to the Journal News, it named ten municipalities that have consistently avoided adoption of the county’s model ordinance that mandates a minimum of 10% affordable units in all new housing developments.

Those jurisdictions are believed to be Briarcliff Manor, Bronxville, Buchanan, Eastchester, Harrison, Mount Pleasant, Pelham, Pelham Manor, Tuckahoe, and Yorktown.

Peekskill’s neighbor Buchanan has been criticized for blatantly avoiding attempts to provide open and affordable housing. In 2016, the village rejected a proposal for 66 affordable senior apartments when it became clear that the units would be made available to residents throughout Westchester. The village recently approved the site for a 100-unit market-rate development.

Robinson’s final report on the Westchester Consent Decree is expected to be released in the coming weeks.

In July 2020, the Peekskill Planning Commission and Common Council began moving toward adopting an affordable housing ordinance based on the “Model Ordinance” provided by the county as part of the federal lawsuit settlement. In its existing form, the proposed Peekskill law would require developers to provide at least 10% of HUD-defined affordable units in each 10+ unit project, and at least one affordable unit in complexes containing 5 – 9 housing units. In early November, the Council hired Rose Noonan, Executive Director of the Housing Action Council (a Hudson Valley nonprofit housing advocacy group) as a consultant to assist the city in navigating the uncharted waters of adopting and administering an affordable housing ordinance.

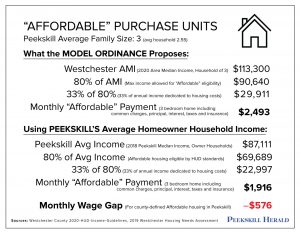

But some like Peekskill Common Council Member Vanessa Agudelo think the Model Ordinance provisions don’t go far enough. “I think it’s better than nothing; it’s something that people will hang their hat on and say, “we have affordable housing”. But 10% does not at all address the need that exists in Peekskill, especially when you consider that the developers work off a Westchester AMI number.”

Agudelo continued, “If we were truly committed to alleviating the hardship of those severely rent burdened, we would pass a much more robust ordinance, one that would set aside 40% of units for a mixture of incomes between 50%-100% of the AMI. If it is financially impossible for the developer to meet 40%, the ordinance could include the ability for them to meet half of the requirement (only after thoroughly documenting their financial hardship), and instead pay into a fund that would be used to address local housing issues in other ways. This addresses the needs of our current residents and is one way we can ensure both affordable and workforce housing continues to be built in our city.”

She also points to the need to preserve existing affordability. “In Peekskill we have the opportunity to pass something like the Emergency Tenant Protection Act. Rent stabilization could exist here in Peekskill for buildings that were built before 1974 and have over six units. Those are ways of securing the [affordable] housing that we have now and protecting it from being sold off in the future.”

The Workforce Gap

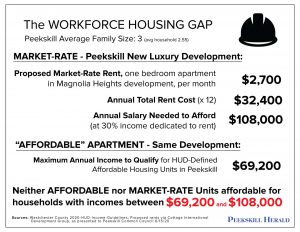

One thing almost everyone agrees on is that any model of affordability needs to provide for a range of incomes. An unintended consequence of legislated affordability that only provides for market rate and HUD-defined affordable units is creation of what some call the “workforce housing gap”: an income range, particularly among households with two or more incomes – where the combined household salaries disqualify the family from consideration for the “affordable” apartments – but whose total paycheck falls well short of what’s needed to afford market rate rents.

In Peekskill we see the workforce gap manifesting in developments like the proposed Magnolia Heights project. At 60% of AMI, a 3-person household (often a younger couple with one child) would be limited to $69,200 total income to qualify for a one bedroom “affordable” unit there. But the same unit at the proposed market rate price of $2,700 per month – would require an actual annual income of $108,000 to limit rent to 30% of the family’s annual budget. For households in the middle, earning $70,000 to $108,000, the apartment designated “affordable” would be unavailable due to their income; and the market rate unit would be a budget buster.

Deputy Mayor Vivian McKenzie reiterated this on Wednesday: “I believe we need to address affordable housing in our code to ensure that new developments allow for affordable and mixed income housing. We must address housing for those whose income is too high to get subsidies but is not high enough to pay market rate. If we do not focus on “workforce housing” we will become a city severely divided by income – those with lower incomes who can access housing assistance and those with high incomes who can purchase or rent any housing of their choice. “Workforce housing” has been overlooked and these individuals unfortunately may leave the city in search of less expensive housing if we do not address this.”

645 Main Street

In September 2020, local developer Wilder Balter Partners broke ground on an 82-unit apartment building on the north slope of Peekskill’s MacGregory Brook between Main Street and Central Avenue. The project is described as “workforce housing” and has been heralded by state, local and county officials as a model for providing truly affordable housing across a range of income levels.

The 645 Main Street development is expected to have rents in a range affordable for tenants earning between 40% and 80% of Westchester’s AMI ($50,320 to $100,640), including one-bedroom units priced as low as $900 per month. The project came about via a complex array of funding sources, with state and private agencies providing millions of dollars in financing, tax credits and other incentives, including $6 million in brownfield cleanup funds, and a combined $8 million from Westchester County Housing Implementation and Land Acquisition Funds thanks to the project’s affordable housing component. And the LEED-certified building received millions in tax-exempt Climate Bonds thanks to its energy-efficient design.

As permitted by the zoning code, the Peekskill Common Council and Planning Commission approved an additional floor of “bonus height” to facilitate more units than per the existing zoning, in exchange for providing amenities such as dedicated parking for the adjacent Kiley Youth Center, a new public water main connection between Main Street and Central Avenue and a public walkway connecting Main Street and Central Avenue.

John Bainlardi, Vice President at Wilder-Balter points to one upside for a developer willing to negotiate the complex funding scheme necessary to make a 100% affordable project like 645 Main Street work: “Generally speaking, the risk for the developer of affordable housing is mitigated relative to the risk for the developer of a market rate product in large part because the demand for quality affordable housing is so high, particularly in many of the communities like those in Westchester County. The developer is renting or selling ten cent apples for seven cents and there is little affordable product available, so developers and their funding partners will have less concern about successfully renting the units and/or achieving full occupancy and stabilization.”

Two Sides of the Valley

In July 2020, following months of developer presentations and public input, the Peekskill Common Council finally took up the measure to sell the city-owned vacant lots along Central Avenue to Cottage International as part of the building site for its proposed Magnolia Heights apartment complex.

In a spirited discussion prior to the vote, Councilwoman Vanessa Agudelo expressed her frustration that, while in an earlier form, the project had included a high percentage of affordable units, over the course of several meetings the developer (at the behest of Council members) had reduced the ratio of affordable units down to a bare minimum 10% of the complex, with 90% of apartments to be priced at the high end of the Peekskill luxury market. She made the case that HUD-defined affordability is actually unaffordable to low-income Peekskill residents, and that therefore the city should use its leverage as the landowner to demand a higher number of units be priced at much lower rents.

Councilman Dwight Douglas countered that Peekskill’s downtown area is already dominated by affordable units, reminding other Council members that 645 Main Street and other projects in the planning stages skew heavily toward affordably priced units. He recommended that in order to maintain a diverse population and healthy tax base, the city should allow a small number of market-rate developments to move forward.

Councilmembers Vivian McKenzie, Kathleen Talbot and Patricia Riley all echoed Douglas’ sentiments, reminding others that Peekskill needs to maintain a mix of income levels. Councilman Ramon Fernandez sided with Agudelo, sharing that he had recently struggled to find affordable housing in Peekskill for his own family, and proposing that the city should pass its own legislation compelling developers to provide a minimum affordable component in all new housing projects.

In the end, the Mayor and Common Council voted 5 to 2 to sell the Central Avenue properties to Cottage International, which has yet to break ground on the site. The project still needs to go through review by the Peekskill Planning Commission, which will look at environmental and traffic impacts, and the Council will still have to approve a zoning variance for the developer before any building can take place.

In some ways, the narrow valley of MacGregory Brook is the perfect metaphor for Peekskill’s housing dichotomy. If Magnolia Heights gets built in its current form, its 70-market rate and 8 affordable apartments will look directly across Central Avenue at the 82 units of “affordable workforce housing” in the 645 Main Street building currently under construction on the slope leading down to the brook.

Can the current mix of affordable and market-rate developments coexist and provide sufficiently affordable housing options for Peekskill’s current population? Will proposed mandatory affordable minimums lower the bar and give Peekskill’s lower-income residents new housing options? Will developers be willing to navigate the complexities of financing workforce housing without legislation forcing them? Or will demand – combined with financial incentives and lower risk for developers – inevitably propel the supply, and eventually help drive down rents for everyone?

The answer may soon begin to take shape on the steep hillsides of Central Avenue.