By Jim Striebich

In June 2020, in the wake of nationwide protests over the unjust police killings of a number of persons of color including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice and hundreds if not thousands of others, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 203, directing every local government with a police force to perform a comprehensive review of their department’s deployments, strategies, policies, procedures, and practices. Each municipality was directed to develop a plan to improve their police agency’s practices, promote community engagement to foster trust, fairness, and legitimacy, and to address any racial bias and disproportionate policing of communities of color.

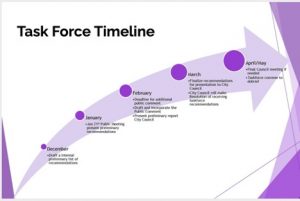

The Herald last checked in on Peekskill’s Police Reform Task Force on October 1, 2020. In the nearly four months since its first public meeting, the Task Force has moved a long way towards fulfilling its mandate of providing an initial report and recommendations to New York State by April 1, 2021 in order to keep state funding in place.

Last Thursday, January 21st, the Task Force held its fourth public meeting via Zoom, with a status report from each of five subcommittees (a sixth “Organizing” subcommittee is focused on the process at large); followed by a lengthy public Q & A

session during which a half dozen Peekskill residents engaged Task Force members including Police Chief Donald Halmy

on a number of issues and concerns. The meeting ran over two hours.

on a number of issues and concerns. The meeting ran over two hours.

The five subcommittees who presented updates have each been developing a pool of ideas for improving police transparency, addressing concerns over perceived systemic racism within law enforcement, and improving the relationship and trust between officers and the public – particularly among Peekskill’s people of color. Over the coming weeks, the proposals outlined here are to be prioritized, streamlined, and pared down to those that are most likely to have a significant impact, as well as most realistic to implement given there’s been no additional budget nor staffing allocated to accomplishing changes.

In last Thursday’s meeting, the Transparency & Accountability Committee proposed a new, public-facing Peekskill Police Department website that would give residents an opportunity to see demographic statistics around police interactions, file complaints against officers, and perhaps be able to view a redacted version of the department’s Police Procedures Manual.

Other recommendations included seeking national accreditation for the department, and most notably, forming a city-funded, independent police oversight board which would review and investigate complaints about officer misconduct such as police brutality and provide reports to city residents. Civilian-police oversight boards have been a hotly-debated topic nationwide; on one hand seen as a powerful watchdog tool that brings visibility into what’s often seen as an extremely insular police culture. At the same time, police unions have often successfully challenged the authority of such panels, sometimes stifling their ability to affect real reform.

The Recruitment and Hiring Committee presented a number of proposals, including reforming the current “Rule of Threes” hiring process for officers, which restricts the department’s ability to choose the best hiring candidates; a new Police Explorers program for 14 to 21 year-olds to increase non-confrontational interaction between police officers and Peekskill youth; and a Public Safety Academy, which would allow high school students to take criminal justice classes and graduate in five years with both a high school diploma and an associates degree – a track meant to provide a natural flow of local cadet candidates into the city’s police department.

A Policies and Procedures Committee – which includes Chief Halmy – is focused on reviewing and revising the Peekskill Police Patrol Manual, looking at areas such as use of force, arrest procedures, and dealing with mental health issues during police calls. Those and other procedures have led to many of the recent negative and often violent interactions between officers and constituents.

The Education, Training and Equipment Committee hopes to introduce new anti-racism education for police employees, with instructors chosen by community members. They also see a need for expanding dash cameras to all police vehicles, with video recording whenever the cars are running – instead of the current standard of recording only while “lights and sirens” are activated.

Other potential initiatives shared by the committee include expanding the use of “approachable” police vehicles such as patrol bicycles and ATVs; holding public forums to share information with the public; and improving officers’ understanding of implicit biases and their knowledge and understanding of cultural differences within the community.

Perhaps most significantly, the Education Committee hopes to introduce crisis intervention training for police, to help officers recognize and deal with non-criminal behaviors such as mental illness and substance abuse. Ultimately this training could lead to creation of a Crisis Intervention Team – an alternative to conventional policing meant to provide mental health support where appropriate, and avoid conventional outcomes such as arrests and violence that often result from untrained officers being expected to deal with mental health issues on the street.

Finally, the Community Engagement Committee is focused on the concept of “community policing”, a broad term that involves expanded partnerships between police and the local community – which has been shown to reduce crime and improve trust between police and civilians. They propose to support community policing with a series of listening sessions between Peekskill police and residents, where the community can share their concerns in a safe setting and create an ongoing dialog between these stakeholders.

Following the subcommittee presentations, several Peekskill residents asked questions, and provided input and feedback to the task force.

Resident Ingrid Whitman suggested that anti-bias training extend beyond racial sensitivity to also include LGBTQ and gender bias concerns.

Tanya Dwyer, a Peekskill resident and attorney who recently witnessed a domestic dispute near City Hall, asked if officers are trained to recognize domestic violence – even when there’s n obvious physical injury. “Lay people don’t recognize domestic violence if there’s no physical injury involved,” said Dwyer. She went on to suggest the police department utilize local social services resources to help. Chief Halmy responded that the department already uses Victims Assistance Services as a sort of “info station” to direct victims to additional services as needed.

Student and community activist Sage North initiated a discussion around the School Resource Officer (SRO) program at Peekskill High School, saying she is not comfortable with having an armed officer in the school, for fear that their weapon could fall into the wrong hands. This led to a long back-and-forth, with several Task Force members indicating they feel the SRO program is a valuable way of integrating police into the community and building trust among younger residents.

When asked by Committee Chairperson Jennifer Carpenter if she felt a more deliberate annual introduction and roll-out of the SRO program to students would help, North responded “I definitely feel that…communication would bridge a lot of gaps. More contact and communication between the students and officers…is very important. If we can’t stop officers from being in our schools, we need to be able to have a connection with them.”

Katherine Quezada, a Peekskill High School student serving on the Community Engagement Committee brought a different perspective: “My friends who come from other countries – my Hispanic friends – they really appreciate [the SRO program] because we don’t have anything like that in our countries. So it’s a great thing for us.” All parties in the conversation seemed to agree that not every officer is cut out for the role, and that SRO officers should be carefully chosen.

The Police Reform Task Force held a daylong retreat on Saturday, January 23rd to allow leaders to begin boiling down the long list of proposed initiatives into a more concise, coherent and realistic series of proposals, which will go into a Draft Plan to be made available to the general public for comment beginning February 4th. The next public meeting – at which the Draft Plan will be discussed – will be held on February 11th, followed by acceptance of written public comments.

Finally, in March, the Peekskill Common Council will discuss and eventually vote on the Draft Plan, which needs to be adopted and presented to New York State no later than April 1st or risk the penalty of loss of state funding for the police department. To paraphrase City Manager Andy Stewart, April 1st is the halfway point of the process: “[It’s] the 50 yard line, because the delivery of this report will be another chance to begin again, and continue work on implementation and discovery as we go forward”. The timeline presented last Thursday indicates the task force expects to begin implementation of reforms throughout 2021 and 2022.

Like most well-intended public initiatives, the success of the Police Reform Task Force depends not only on community participation and the willingness of all stakeholders, but also on finances and funding. Reacting to a proposal by Ms. North to consider replacing six unfilled police officer positions with social workers, Chief Halmy made that point bluntly. “The number one thing that will hold us back from implementing all these ideas is staffing. At the number we have, we basically can minimally service the community by answering calls. That’s what our number today gives us. Nothing more than that.”

Categories:

Progress Report: Peekskill Police Reform Task Force

January 28, 2021

More to Discover