Our two part series examining housing development and affordability. Second part posts on Saturday morning.

By Jim Striebich

One of the hottest topics being discussed in Peekskill last summer was “affordable housing.” The debate crescendoed when the Common Council considered selling three vacant city-owned lots along Central Avenue to a developer – Cottage International Development Group (CIDG) – who was seeking to build an apartment complex on the hillside between South Street and Central Avenue, just off Washington Street.

The public discourse centered around the developer’s proposed mix of “affordable” and “market rate” rental units in the two-building complex tentatively called Magnolia Heights. When CITG first presented the project in December 2019, they proposed a two building rental complex with all of the 167 units priced at market rate. At that meeting, Common Council members requested a revised proposal to include a number of affordably-priced apartments.

The developer’s representative Tom Conneally returned to the Common Council in January 2020 with a project adjusted to include nine “workforce priced” apartments in one of the two buildings. The nine units would be priced to make them affordable to households earning 90% to 120% of the median income across Westchester County.

When Conneally returned in May with a new model featuring up to 75% of units priced as “affordable workforce” and 25% at market rate, several Council members – citing the new all-affordable development directly across Central Avenue – expressed concern that the ratio threatened to concentrate too many affordable apartments in that block, and would limit the positive financial impact to Peekskill’s downtown businesses. They requested CITG revise the rental pricing again, including a larger proportion of market rate apartments.

In the leadup to the June 15th Common Council meeting, nearly 50 Peekskill residents and organizations – citing Peekskill’s large “affordability gap” – called for the Council to demand a higher percentage of so-called affordable-rent units, in exchange for the sale of that parcel.

During the June meeting, after presenting yet another pricing proposal – which ignited another round of Council discussion, CIDG representative Tom Conneally called on Council members to look at the larger picture: “This is TOD, transit-oriented development. It isn’t about this one building. It should be a ten-year plan with thousands of units, and how to make it work so that it provides money to all the city agencies.”

A Federal Lawsuit

The topic of fair and affordable housing has been swirling in Westchester for a very long time.

A 2009 federal lawsuit brought against Westchester County by the Anti-Discrimination Center of Metro New York found that from 2000 to 2006, Westchester County had illegally made false claims by accepting federal housing grants, while failing to actually “affirmatively further fair housing”. The resulting consent decree required the county to create 750 new units of affordable housing across its least diverse municipalities. A number of those Westchester locales were seen as obstructing fair housing choice, often by maintaining zoning codes that restricted multifamily and affordable development (“exclusionary zoning”). The county was required to strongly encourage towns and villages to enact legislation to increase both diversity and affordability – two traits seen as indelibly linked.

But what exactly is “affordable housing”? And is it positive or negative (or something in between) for Peekskill? And does that even matter, if it’s the morally-correct thing to do? If – as many progressives have stated recently – housing is a basic human right?

Defining Affordable

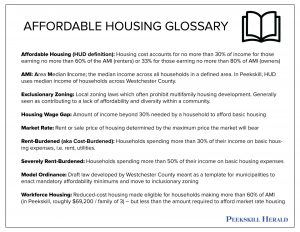

The most recent detailed local data on the subject comes from the 175-page “Westchester Housing Needs Assessment” from November 2019. The report, commissioned by the county from a third-party research agency, defines affordable housing as:

“a housing opportunity that requires a household to pay no more than 30 percent of its annual income for housing. Households that pay more than 30 percent of their income are cost burdened and those who pay more than 50 percent are considered said to be severely cost burdened.”

Calculations are based on several standards, but most notably Area Median Income (AMI)

AMI is calculated by household size and published annually by the federal department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). It’s a median income across all of Westchester County – which makes it a particular bone of contention for local affordability advocates, who say the wide disparity in income levels across the county unfairly skew the statistic against residents of lower-income municipalities like Peekskill.

HUD-compliant affordable rental apartments are available only to households earning no more than 60% of the local Area Median Income. Those apartments are priced at no more than 30% of that 60% of AMI figure. For homeowner units like condos and co-ops, affordable units are limited to households earning no more than 80% of AMI, and mortgage + utility costs are set at 33% of that annual income.

Peekskill Incomes vs. Westchester Incomes

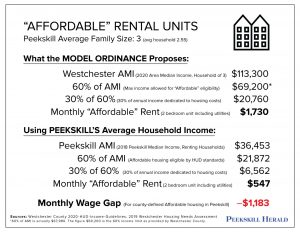

This is where the discussion sometimes turns contentious. Westchester is one of the wealthier counties in the US. For FY 2020, HUD AMIs for Westchester ranged from $88,100 for individuals, up to $146,000 for 6-person households. The AMI for a 3-person household is $113,300 per year.

But in Peekskill, the true average income is significantly less than the HUD-defined, county-wide AMI. The average Peekskill household’s (2.55 people) estimated income is only $55,500 per year. Broken out by homeowners vs renters, the 2019 report states that Peekskill has the lowest average household incomes in the county for both groups ($87,111 and $36,453 respectively).

Because AMI varies by household size, it’s impossible to define “affordable” by a single number; but to provide some scale, a two-bedroom rental apartment in Peekskill costing $1,730 per month (including utilities) is considered by HUD to be “affordable” for a family of three. But in Peekskill, where the average renter’s household makes less than $37,000 annually, that same two bedroom apartment would need to cost $547 a month to be truly affordable – using HUD’s own standards.

In the 2019 report, Peekskill is cited as one of only four Westchester municipalities where the housing wage gap for renters is over $1,700 a month for market rate apartments. Even at “affordable” rates as defined by HUD, the average Peekskill rental household comes up almost $1,200 short every month.

Legislating Affordability

The 2009 consent decree agreed to by Westchester County contained a number of mandates including that the county create “Model Ordinance provisions” and encourage local municipalities whose existing zoning was seen as an impediment to fair and affordable housing to begin adopting the new laws.

A primary Model Ordinance provision requires developers of multi-unit housing to include at least 10% of HUD-defined affordable units in each 10+ unit project, and at least one affordable unit in complexes containing 5 – 9 housing units. The Westchester Model Ordinance contains a number of other requirements and recommendations including incentives for developers, maintenance of affordability for 50 years, setting minimum unit sizes, and marketing the units to racial and ethnically-diverse populations.

In the midst of the affordability discussion last summer, the Peekskill Planning department used the county’s Model Ordinance provisions to draft a proposed affordable housing ordinance for the city, and presented it to the Common Council. In early November the Common Council hired Rose Noonan, Executive Director of the Housing Action Council (a Hudson Valley nonprofit housing advocacy group) as a consultant to assist the city in navigating the uncharted waters of adopting and administering an affordable housing ordinance. The Council has yet to adopt an ordinance.

“Our council has been very focused on ensuring both affordability and income-diversity in Peekskill,” said Deputy Mayor Vivian McKenzie on Wednesday. “We have contracted with Ms. Noonan to help in designing an ordinance that will address these issues. We expect the ordinance will be ready for public review and a vote in the next few months.”

Striking a Balance?

There are many who argue that demanding too many affordable units in all new housing developments has potential downsides, including:

Concentration of poverty. Many believe the healthiest urban environment contains a diversity of income levels, and fear that if too many housing units are marketed to low income residents, the result can be disinvested, impoverished neighborhoods with few local businesses. “It takes residents with some disposable income to support the retailers, restaurants, and coffee shops we all want in our downtown” is a typical refrain.

Lack of tax base. The argument is that a certain amount of market-rate housing is necessary to fund schools, city services and maintain or expand infrastructure. The contention is that the often temporarily lower taxes generated by affordable housing (due to developer incentives) is insufficient to fund these things, leaving city services under-funded, overwhelming schools and other infrastructure, or shifting the tax burden onto other city property owners.

Loss of developer incentive and interest. The thinking goes “If a developer sees local affordability requirements as driving down profit or even making projects financially unfeasible – they’ll just take their investments elsewhere.”

Some who subscribe to this belief think the best solution is to allow a mix of market-rate and affordable projects to coexist, and provide developer incentives such as additional density or height bonuses as rewards for including affordable units. Many believe a combination of minimum affordability legislation, combined with incentives – a “carrot and stick” approach – is the best way to strike a balance.

In Peekskill, where current city code has no affordability requirements, the majority of downtown rental apartment buildings are nonetheless considered affordable or subsidized in some way, often via government programs or not-for-profit organizations. Some new projects like One Park Place are 100% market rate; others, like the Gateway Townhomes and Lofts on Main, have a mix of market rate and affordably-priced units; and still other buildings such as Bohlmann Towers, Wesley Hall, Peekskill Plaza, and Crossroads – contain 100% income-restricted affordable units.

Some of the in-progress Peekskill housing developments contain nearly all market-rate apartments. One Park Place, the nine-story apartment building being built at Park and Broad Streets, contains 181 market rate rental apartments. Two smaller complexes approved in 2020 on South Division and South Street contain a total of 73 new market rate apartments.

Most of the smaller, historic mixed-use buildings contain market rate apartments that by city code can only be rented to certified artists, including musicians and other performing artists. The Artist Certification program was created in the 1980s and designed to help revitalize a downtown filled with vacant commercial spaces. Today, the high demand for downtown residential spaces has raised rents and made it difficult for many artists to find housing in the city’s core.

In part 2 of this article on Saturday, we’ll look at Peekskill’s record in creating affordable housing and examine the challenges for middle-income households looking to live in Peekskill.

Categories:

Building for the Future: Peekskill Development and Affordable Housing

January 14, 2021

More to Discover