Treasure on the Hudson and Captain Kidd’s Humbug

December 24, 2021

When we think of the term “humbug” today, usually Ebenezer Scrooge, that miserly old curmudgeon from Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” comes to mind. Yet when looking at the curious markings on an 1854 Peekskill area map, it describes the site and story of one of the greatest scams of the 1800’s – Kidd’s Humbug.

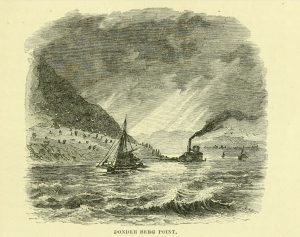

The night is dark and stormy as Captain William Kidd’s treasure ship, the Quedah Merchant, approaches Caldwell’s Point at the base of Dunderbergh Mountain. This part of the river is the beginning of the Race, the treacherous Southern Entrance to the Hudson Highlands. Chased by British warships, Kidd is wanted for piracy and murder. As they approach this deadly spot, his crew panics at the thought of running the Race on a stormy night and scuttle her. Or the ship runs aground. Or hits a rock. Or she is set afire and sunk by Kidd. There are many versions of the story. William Kidd and his crew take what they can, but the bulk of the treasure goes down with the ship. The year is 1699.

So the legend goes, with Kidd and his crew escaping overland and ending up in Boston, where Kidd is arrested. He was sent to England, tried, and hanged in 1701.

There has always been a fascination with Captain Kidd and his treasure. His exploits inspired Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Stories of his hidden spoils place it at dozens of locations on the Eastern seaboard from North Carolina to Long Island.

Howard Pyle (1921)

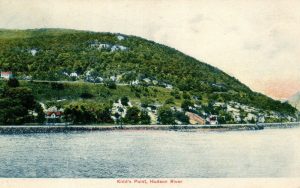

By the time the 1840s rolled around, Kidd had been dead for almost 140 years, and there were plenty of rumors about a burning treasure ship going down off Caldwell’s (now Jones) Point. Kidd had left treasure on Gardiner’s Island, which the British had recovered, but was that all of it? There must have been more!

The thought of pirate treasure in the Hudson River Valley, so close to Kidd’s New York City home, was irresistible to Abraham G. Thompson, a descendant of the Gardiners. He acquired 100 acres at the foot of Dunderbergh and the water rights off Caldwell’s to look for the wreck.

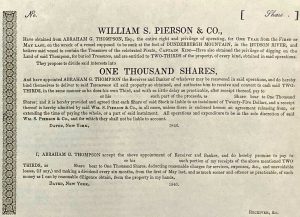

In June 1844, he published a pamphlet titled “An Account of Some of the Traditions and Experiences Respecting Captain Kidd’s Piratical Vessel,” a prospectus that described the background of the wreck. In 1845 the Captain Kidd Salvage Company was formed with $100,000 of shares offered in $100 increments and were sold in the U.S. and Great Britain.

When test borings revealed traces of silver, the company had no trouble raising money. Soon 50 men were employed building a cofferdam around the location, with water pumped out by steam engines. It was visible from across the river in Peekskill, and riverboat captains would slow down so that their passengers could see the spectacle.

From the very beginning, there were skeptics. Some historians suggested that the cannons recovered might be from a galley sunk by the HMS Vulture during the Revolutionary War. Then, William Richards, editor of the Republican, a Peekskill newspaper, wrote in February 1845 that the two antique cannons brought up from the wreck were initially delivered to the Verplanck dock. Curious workers had opened the crates and, seeing that the contents were two cannons, sealed them back up. They later recognized the pair of cannons when they re-appeared at Caldwell’s as evidence of Kidd’s lost ship.

Thompson countered his critics, producing a newly raised cannon from the river bottom and fragments of gold and silver that had come up in some of the borings. Then he published the testimony of a mesmerist (clairvoyant) who visited the wreck while in a trance in Lynn, Massachusetts, describing it and the treasure in great detail. Spiritualism was gaining popularity at this time, and between the testimony of the mesmerist and Thompson’s recovered items, his investors were now satisfied and hopeful.

Benson J. Lossing, “The Hudson – From the Wilderness to the Sea” (1866)

Unfortunately, their hopes were short-lived, and they never saw a cent of return. Lawsuits began in 1846. By 1848 the workers disappeared, the steam engines ceased pumping, and the cofferdam filled with water.

By 1850 the Kidd Salvage Company was embroiled in lawsuits. One of the workers at the cofferdam testified that he had lowered a brass cannon into the water and burned the shipping crate. He claimed that gold and silver coins purchased from an antique shop had been treated with acid to appear old when ground up and affixed to the boring augers.

While the memory of the scam would eventually fade, the cofferdam ruins created a navigation hazard, and the site would appear on maps as “Kidd’s Humbug” from 1854 to the 1930s.

In the 1800’s “humbug” was a common expression for a deception or scam. “Bah, humbug!” is Scrooge’s response to the joy others are experiencing at Christmas. To Ebenezer, Christmas was a total fraud, and the warm feelings people felt around it, insincere.

The great P.T. Barnum was a regular user of this word and embraced it. He freely admitted that most of what he presented was humbug. However, he made a distinction between deception and swindling.

Decades after the Kidd episode, Peekskill experienced another infamous humbug when Daniel Craig attempted to sell shares in his bankrupted estate, Mount Florence (Chapel Hill). Like the Captain Kidd Salvage Company, his scheme also proved a scam.

And, in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” L. Frank Baum has an entire chapter titled “The Magic Art of the Great Humbug.” Here, the Wizard attempts to give the scarecrow brains, the lion courage, and the tin man a heart. The Wizard admits that he cannot do any of this and is most certainly a humbug. Dorothy even refers to him as “The Great and Terrible Humbug.” As for local folklore claiming someone at either the dock or train station told a young L. Frank Baum to “follow the yellow-brick road” to get to the Peekskill Academy? Pure humbug.

But those are stories for another time.

Kirk Moldoff, a professional medical illustrator, has been researching Peekskill history for over three decades and has lectured extensively on the rich history of this area.