When it comes to lists, being the first in eight out of 12 categories might seem worthy of bragging rights. Of course it depends on what the list is compiling.

Significant air quality issues and how they affect the Peekskill community have led many activist groups and residents of the area to denounce the city’s WIN Waste Westchester trash incinerating plant, formerly known as the Wheelabrator plant. WIN Waste, they claim, is a leading source of air pollution in the county, and activistgs warn of health consequences for Peekskill residents, as well as others nearby. The plant is considered a leading reason for the city’s classification as an environmental justice community, a designation conferred by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. The label means Peekskill has a vulnerable population that needs to be protected from the harmful effects of pollution. (For more information about this designation, see our recent article about environmental justice communities.)

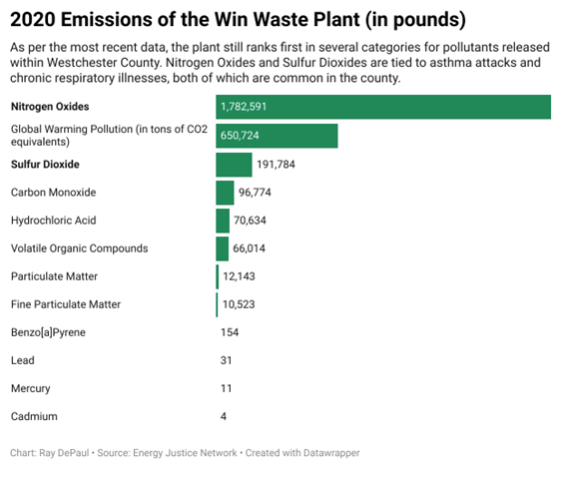

According to Environmental Protection Agency data, WIN Waste is the largest air polluter in Westchester County. Alongside a sewage treatment plant, a gypsum plant and a high-pressure gas pipeline, WIN Waste stands out as a greater detriment to overall health in the area, prompting controversy within Peekskill and beyond, including the rest of New York State.

The trash-burning plant’s Title V operating permit expired in 2021, but per New York State law, the plant may continue operation while it is under review for a permit renewal. The federal Clean Air Act Amendments require Title V permits for all facilities where air pollutant emissions are “greater than major stationary source thresholds,” which is around 100 tons per year. WIN Waste surpasses those thresholds.

There were only four categories among the 12 listed above in which the trash-burning plant did not rank first in Westchester. All of the categories in which the plant ranked first have negative effects on respiratory illnesses, including asthma.

In 2018, Westchester County had a rate of 10.8% of adults with asthma, 0.7 more than the statewide average, according to the county’s Community Health Assessment. Though compounded by other factors, having a long-standing air pollutant generator in the backyard is likely linked to this higher rate.

Complaints about the trash-burning plant range from concern about the expiration (and extension) of its operating permit, and the plant’s age and approaching obsolete status, to how it impacts the surrounding community.

Fifty trash incinerators in the United States have closed since 2000, with most not lasting longer than an average age of 25 years. The WIN Waste facility was established in 1984 and is quickly approaching its 40th anniversary of operation. (See the history of how this incinerator solved the county’s waste problem and came to be located in Peekskill, which is Part 1 of a two-part article in the Peekskill Herald published in 2021. Part 2 discusses the costs, benefits and alternatives to incineration.)

WIN Waste’s plant has been authorized by the state to keep running for another decade or so, which would make it one of the longest-running trash-burning facilities in the country. As only a very few have made it this far in their lifespan, the activist groups say it remains to be seen what issues may arise. They cite such dangers as sudden failure, which could disrupt the community.

Many of the closed incinerators discontinued trash burning mainly due to a move toward cleaner energy sources. Those who oppose WIN Waste ask why hasn’t Peekskill and the Westchester County government moved toward a similar future.

“This is a piece of infrastructure. It was designed with a certain lifespan in mind,” said Dr. Courtney Williams, a Peekskill resident, scientist and founder of Westchester Alliance for Sustainable Solutions (WASS). “It has far exceeded that lifespan, and if we do not prepare for its eventual demise and decommissioning, we will be caught in a massive financial hole.”

When educating others on the impact of the Wheelabrator facility, Williams has come up with a mnemonic: “We need to remember the three P’s: Incineration is bad for people, the planet and our pocketbooks.”

WASS seeks to “sound the alarm on the harm incineration does to Peekskill residents and the planet,” according to its fact sheet, which attempts to clear up potential misconceptions about WIN Waste. In an opinion piece published in the Journal News this past February, Dr. Williams and Dr. Michael Shanks, an adjunct professor at New York University’s School of Professional Studies, and former resident of Peekskill, explain why they believe Westchester county can’t tolerate the incinerator any longer.

WASS hosts awareness-raising events about the incinerator, including a recent event where presenters included New York State Senator Pete Harckham, a longtime critic of the WIN Waste’s operations.

“We know the challenges and problems inherent with waste incineration. It’s challenging and we need to get to the organization’s point of zero waste,” Senator Harckham said.

New York State Senator Pete Harckham, chair of the legislature’s Committee on Environmental Conservation. Photo: nysenate.gov

Legislation to protect the environment and combat facets of climate change has been at the forefront of state and federal legislation over the past year. Earlier this year saw passage of the Packaging Reduction and Recycling Infrastructure Act in New York State, which was sponsored by Harckham. On the federal level, the Biden administration moved to decrease the presence of “forever chemicals” in the nation’s drinking water.

The state’s Packaging Reduction and Recycling Infrastructure Act requires a 10 percent reduction in plastic packaging by 2027. After that date, there must also be a recycling rate of 70 percent on plastic, glass, cardboard, paper and metal packaging. After 12 years, there must be roughly a 30 percent incremental decrease in plastic packaging.

“It was a monstrous fight, I must say, and we took on some of the largest companies and industries in the world,” said Harckham. “They were in opposition to that bill because it would change the way that they would have to do business.”

Some 22 percent of New York State residents opposed the bill according to Beyond Plastics, a nationwide team advocating to end plastic pollution. Getting the bill passed was an uphill battle for both advocates of the act and senators such as Harckham.

The passage of this act should trigger a decrease in materials that end up going to the trash incinerator plant, further rendering it less necessary and even obsolete.

In Westchester County, another significant bill in January of this year addressed the challenge of reducing the ubiquitous use of plastic over time. As a result of an advocacy campaign led by WASS, the 2024 Westchester budget earmarked the $90,000 for a waste reduction study [see related story]. It’s a significant project and reducing the use of plastic and other waste will take some time.

The WIN Waste plant’s impact on the community has positives as well. In Peekskill’s 2024 budget, WIN Waste is shown contributing an estimated 6.7 million dollars to Peekskill. That’s sizaable 13% of the city’s total operating budget of just over 51 million dollars. The WIN Waste Westchester website says it “converts about 631,000 tons of post-recycled waste into renewable energy” each year.

How to sort out all of the alternatives and move forward?

Moving forward

Lisa Antonelli, a steering committee member, and co-lead of the Waste Nothing Committee of the Green Policy Task Force in the nearby river town of Irvington, has a suggestion on next steps.

“Residents of Irvington are surprised that Westchester County and the great state of New York are not doing more to help reduce waste materials in our communities,” said Antonelli. “The education materials are available but nobody knows about them. Ideally, we need a campaign, similar to the NY Quits [Smoking] campaign that makes it easy for residents to educate themselves.”

“The plant is not going to close tomorrow. It can’t close tomorrow. There’s nowhere to put the waste,” Harckham said. “What we’ve been working on, number one, is make sure the public is heard, and if the plant gets a new air permit, [that] it’s as safe for public health as possible.”

“That any entity can keep running while their permit is under review is a long-standing issue in New York State,” said Harckham. “This can go on for years. The other thing that we have to focus on is reducing the amount of waste that’s going to both landfills and these waste incinerators.”

Trash sent to the Peekskill’s incinerator plant comes from different counties, according to the Energy Justice Network. The majority comes from Westchester, but a significant percentage comes from Connecticut and Dutchess, Orange, Putnam and Rockland counties.

“The ultimate goal of ‘zero waste’ and elimination of the need for the Wheelabrator incinerator requires multi-dimensional and long-term transformation at all levels of our economy and culture,” Charlotte Bins, also of Irvington’s Green Policy Task Force, told a reporter. “Not just in Westchester County but in the region, as the incinerator receives waste from cities and entities outside Westchester.”

WIN Waste continuing its operation for so long in Peekskill may be partially due to the city’s majority of minority and low-income residents. The city as a whole has a median income significantly lower than the state average.

The WIN Waste plant’s proximity to a concentration of minority and low-income residents underscores the concern over how the continued operation of this plant could add to health consequences among residents, including already vulnerable individuals. Since WIN Waste Westchester pays the city to operate the plant, the city is unlikely to interfere with its operation.

“I’m not happy with our government. I feel that they need to prioritize environmental health a lot more than they do,” said Peekskill resident Tina Volz-Bolgar. “Especially the impact on people of color. If we do want to create equitable systems, we’ve got to look at what we can do for them.”

Residents of public housing facilities in the city have frequently expressed discontent with how these air pollutants lower their quality of life. Due to financial and time limitations, it can be hard for residents of public housing to influence any change.

“I think it’s high time that Peekskill stopped being the dumping ground and having our health sacrificed so that richer, whiter communities could dispose of their garbage,” said Dr. Williams. “It’s time for Westchester County to be held accountable for literally and figuratively dumping this harmful problem on Peekskill.”

“The county will be stuck with over 2,000 tons of trash per day and nowhere for it to go, no existing contract for its disposal, and be paying through the nose on an emergency contingent basis to get rid of that trash, and the city of Peekskill will be left with zero plans for how to fill that gap,” said Dr. Williams. “[All] because they refuse to face facts that this piece of infrastructure is not going to last forever.”

A call to action, especially now as the aging plant awaits a renewal of its Title V permit, is of paramount importance. Not only to the city of Peekskill but to the county and New York State as a whole. Further operation of the plant will only render the surrounding area more susceptible to all of the negative impacts of climate change.

“It is fiscally irresponsible to continue to pretend that this solution is a solution that will exist in perpetuity,” opined Dr. Williams.