Dorothy Longo came to Peekskill with her husband Mike Longo in 2007 because she wanted a kitchen. After living for 37 years in New York City rent controlled apartments with tiny kitchens, they found a weekend home they loved, with a spacious kitchen.

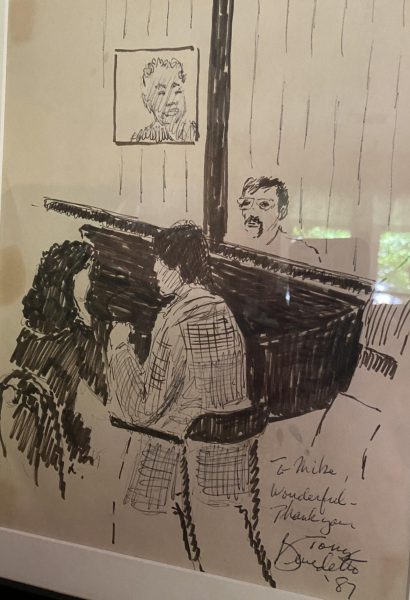

The couple enjoyed the vibe of Peekskill. Mike, an accomplished musician who was, among other things in his illustrious career, Dizzy Gillespie’s musical director and pianist, played the historic Paramount Hudson Valley theater and they both appreciated the vibrant art community in the area. One of the things that attracted her to Peekskill was seeing the Ford Piano sign with the keyboard marquee on South Division Street. “Well, this is home,” she thought.

When Dorothy first met Mike, she was singing and playing piano in cocktail lounges and small venues in the city like the Marriott and the Gramercy Park Hotel. With a strong classical background, she could play standards from the American songbook but felt she wasn’t a skilled improviser. Singing and playing with a guitar player and a drummer, her guitarist recommended she take lessons from his teacher, Mike Longo.

During her first encounter with Mike in 1981, she says she was “taken aback by his presence” which is something that has happened to her twice in her life. She felt a sense of “love and acceptance” that she recalls vividly to this day. For nine months, she didn’t really talk during the lessons. She didn’t think she was progressing and feared Mile might drop her as a student, so she kept her head down and focused on the music. Her improvising did improve a little, but she soon realized it was not her calling.

How the relationship evolved

What cemented her decision to consider her options about continuing lessons with him was the moment she “lost her car, lost her gig and lost her agent in one fell swoop.” When she told her teacher about the incident after breaking down crying during her lesson, Mike listened attentively and invited her out to his show on Long Island that evening.

This began a friendship that grew over the years. They started to work together – with Dorothy typing and editing his music education books. A year later, she knew she wanted to be Mike’s wife and support his musician journey. In 1988, after building the friendship and relationship that would see them through the next 32 years, they were married.

Dorothy and Mike took their time to wed because they wanted to really “get to know each other’s character.” This is one of the principles of the Bahá’í faith which the couple practiced. Their period of adjustment was before the marriage, once they got married they felt perfectly at home together.

Mike was afraid he wouldn’t be able to play if he got married because he had never before had someone who, “knew who he was and supported what he was about and what he wanted to do with his life.” Dorothy says she was, “just plain afraid” because she had not had good experiences with love in her life.” They overcame their respective fears and created an incredible life together.

As a musician who fell out of love with gigging, Dorothy found that she got nervous for Mike when he played. When she watched him play Carnegie Hall, she was terrified for him but saw that Mike had no reservations in his own playing – he was at home on stage. Dorothy was always very in touch with Mike’s musical journey. He was the perpetual student, always working on improving his craft and trying to reach a higher level. As a musician, Dorothy was in the unique position to offer him feedback that could keep him on track to move from level to level. As a critic of himself, Mike was open to learning and implementing constructive feedback to keep improving.

Mike realized early on that Dorothy was an inspiration. What she did for his career and his craft transcends the moniker of muse. She had the nickname “jazz wife” which might not, on the surface, sound like the most liberated feminist ideal, but when you dig into their relationship, there’s an unconditional love and depth of mutual understanding that made their journey together magical.

Dorothy gave Mike the support to keep growing musically with the freedom to explore and expand the artistry of his pursuit. As he turned down high profile accompanying gigs with artists like Tony Bennett, The Tonight Show Band, and Ella Fitzgerald, the pair grew their relationship in parallel with Mike’s craft. Mike believed in his musical endeavors and so did Dorothy. As his wife and professional right hand, and someone who understands the demands of playing an instrument at a high level, she could advocate for him and take care of the logistics of his musical life like no one else on the planet.

Grief turned into a book project

Mike performed in what would be his last concert with The New York State of the Art Jazz Ensemble at the John Birks Gillespie Auditorium in the New York City Baha’i Center on March 10, 2020. He played regularly with the band as part of the “Jazz Tuesdays” program there. Seven days after that concert, on March 17 he went into the hospital and died on March 22 from complications arising from Covid.

When Mike died, Dorothy lost her partner in the most amazing life journey she could have ever imagined. As she dealt with her own grief and worked on processing the flood of emotions, she realized there was something she could do to carry on his legacy and help feel close to him in his absence. She started reading his unfinished memoirs.

She learned so much about him and her relationship through reading his journal entries. She describes the experience as “like watching a movie of their life” and there were stories she had never heard before. She discovered beauty in the opportunity to complete them and bring their story to the world.

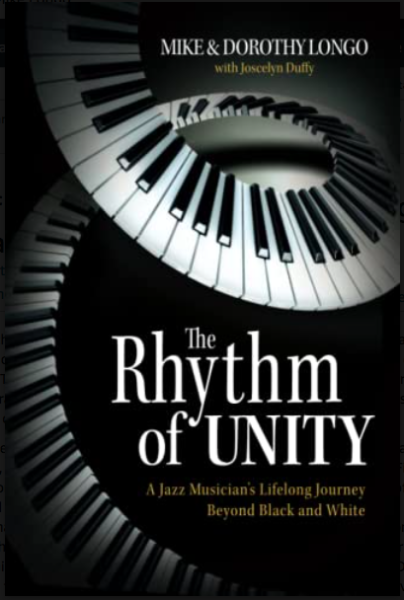

She thought to herself, “This should be a book. This should be out there.” When he was writing it, her advice to him was to, “Write it all down” which led her to realize the book needed major editing. Collaborating with writer Jocelyn Duffy on the structural details, they turned Mike’s story into a spellbinding read: The Rhythm of Unity: A Jazz Musician’s Lifelong Journey Beyond Black and White

She describes the memoir as, “Not just a book about jazz and jazz greats. The book gives a view of the civil rights era that most people don’t hear about every day. It’s a book about hope and it’s a book about how we can connect with our neighbors.” She continued, “How can we all live together and respect each other? When you get down to it, it’s not about all this stuff you see on the news; it’s about people. It’s about telling a story of love and friendship and also, following your dream. Mike never had a backup plan, and he was totally committed to the life he was supposed to live.”

Mike Longo was always aware prejudice is real and that it doesn’t matter where you’re from, the color of your skin, or what your social economic status is. He intuitively had a drive to promote unity and education through music and finding one’s voice. Independent investigation of truth and the oneness of humanity are both central to the Baha’i faith of which Mike and Dorothy practice.

Music running the business or business running the music

In music and the arts, you can either play or you can’t and you’re either dedicated or you’re not – that’s all that matters. In the jazz scene, Mike found there were people on the periphery who DID care about where you were from, what you looked like and that dictated, to some extent, the business and the culture of jazz. His teachings and his playing are a testament to the pure artistry of jazz and carving one’s own path, pursuing what’s most important to transcend any “scene” or “business.”

Her biggest hope is that Dizzy Gillespie’s rhythmic concepts that Mike shared, “will again become central to a jazz musician’s development. “There was a time when music ran the business but now, business runs the music.” She sees so many talented young musicians being chewed up and spit out.

Young players with great chops don’t seem to have the same shot with apprenticeships like Mike had with Dizzy. In the ‘40s to ‘60s, she believes there were real mentor forces at work in jazz. Young musicians would play with established artists and develop their skills through practicing and playing with the best. Now, young artists in music schools don’t go past the imitative phase and into a real creative chapter where they explore their own styles and grow as individual artists.

As a student of the legendary Oscar Peterson in Toronto, Mike was given powerful advice on the musician’s life. Peterson told him to understand where other players are coming from with their styles but to always play your way because that is the pinnacle of all creative endeavors.

One of Dorothy’s goals with the book and Mike’s music is to keep that thread alive in jazz music. To reinforce what Oscar Peterson told her husband so many years ago: the musician is most alive when they are playing their own way and the best way to get there is to develop your chops with a sense of history then move that history in the future with something that is entirely one’s own.

As a musician in Dizzy Gillespie’s band, Mike developed a lifelong friendship with saxophonist James Moody, also in the band. The three of them had a camaraderie and a bond that translated into their playing and their mutual admiration over the years.

To experience the music of Mike Longo, you can ask Alexa who will play everything from his big band songs to his work as the Mike Longo Trio. There’s a YouTube channel called @MrBebopyo, and a website called Jazzbeat.com you’ll find Mike’s educational books, DVDs, and music, and another website dedicated to Mike’s music and musings, called Mikelongojazz.com. “The Rhythm of Unity” is also available as an audio edition as well.