In the idyllic Hudson River Valley, two concrete domes, just barely peeking over the treeline, dot the landscape near a city of 28,000. They belong, as most of the area’s residents know, to the now-decommissioning Indian Point nuclear plant. In theory, the nuclear anxieties around Indian Point could be wiped away once Holtec, the company managing the decommissioning, delivers a near-clean site— at least in terms of structures — to the village of Buchanan where the plant resides.

But what if the site could come to represent something visionary for the surrounding communities? Something beyond its history as the former home of a nuclear power plant?

Architect Jonathan Molloy, who is also a lecturer at the Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, is part of the team that led HALF-LIFE, a class where a dozen students designed a potential new life for Indian Point.

The thesis statement behind this class is adaptive reuse, which asks if a structure can be recycled instead of demolished. Adaptive reuse isn’t an alien concept in the Hudson Valley. There’s a tradition of finding new life for old, largely industrial buildings, with the most prominent example being Dia:Beacon, once a box printing factory transformed into a sprawling museum of contemporary art.

“As a recently decommissioned nuclear power plant, Indian Point presented a rich opportunity for our students to engage with the very current topics of adaptive reuse and sustainability in the built environment. The conundrum it presented to the region, as both a threat of nuclear disaster and a low carbon energy producer providing around a quarter of New York City’s energy, served as an exciting, if not daunting starting point for each of the projects,” said Molloy.

After landing on adaptive reuse as a class topic, both Molloy and Florian Idenburg, Professor for the HALF-LIFE class and partner at SO-IL, the Brooklyn architectural firm where both men work, wanted students to consider questions of energy and the environment. The two architects collectively landed on the former nuclear plant, and this was the prompt the students grappled with for their projects.

“You know, it’s an immense facility right on the Hudson River that has a kind of eerie presence that I think anyone who moves up and down the Hudson knows about but doesn’t know much.” Molloy, who grew up in Nyack, reflected.

Heavy fog and ‘nuclear gravestones’

With their sights set on Indian Point, Molloy and Idenberg decided the next step was to try for a tour. Most of the class’s students aren’t from the Hudson Valley, and Molloy figured this would be their one chance to experience the plant. While initially apprehensive about their prospects, the two professors were met with a surprisingly receptive Holtec after a few phone calls.

The weather on the day of the trip was, in Molloy’s view, “appropriately sort of ominous.” Rain clouds painted the sky, and a heavy fog settled along the river, completely hiding it. The imposing, industrial setting and heavy security presence affected some of the students’ designs, Molloy feels.

“The area that was probably the most intense, in sort of a subliminal sense, was the waste area. The spent fuel rods are stored in what are called dry fuel casks, which are double layered steel cylinders They look something like nuclear gravestones in a grid up on a little hill next to the facility, and they’re still reacting,” Molloy recalled. “The fuel will react for 60,000 years, so they’re still producing heat, which visibly emanates from them,” Molloy recalled.

The students addressed issues beyond the nuclear legacy of Indian Point in their designs. A practical concern was the sharp, 90-foot grade change from the waterline to the center of the lot. Other questions surrounded just how much of the existing structures should be reused and what could be left to crumble. On a more existential level, students were also weary of creating something that would draw too much electricity. Would it be right to build something energy intensive on this spot?

“It’s not just an empty building that you find in a field. The fact that it used to provide a quarter of New York City’s energy while also being considered a major polluter of the Hudson River is a lot to include when thinking about what new life it might have,” Molloy added.

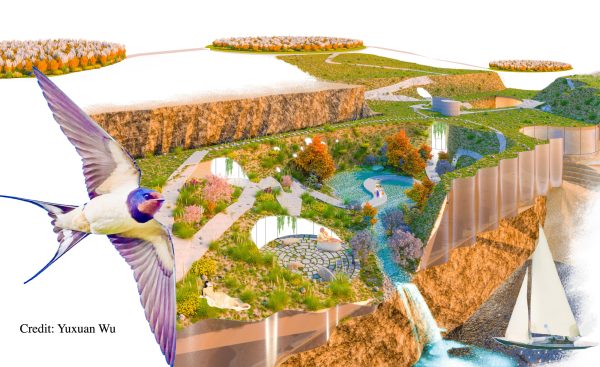

The six projects made for HALF-LIFE ran the creative gamut. One design, by Yuxuan Wu, re-imagined the area with Riverkeeper in mind, turning the organization’s biggest foil into a state-of-the-art base of operations.

“My design proposal aims to restore the site’s natural conditions and integrate space for humans with nature to promote cohabitation and growth for employees, visitors, and wildlife alike. By reconstructing the Indian Point Nuclear power plant site in an organic way, it can continue to fulfill its role, not in generating electricity, but in generating and sustaining life,” explained Wu.

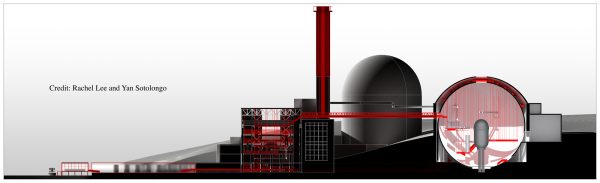

After observing the decommissioning process, another group, Rachel Lee and Yan Sotolongo, would turn the Indian Point buildings into a museum.

“It was a surreal experience walking through the plant and witnessing the massive and discarded machinery. We got fairly close to the giant dry cask storage tanks. Close enough to see heat radiating from the vents, which is a bit frightening,” said Sotolongo. “I became very interested in the idea that these casks contain material that still has no permanent home for disposal in the US. Our project, a Nuclear Power Museum located on the site, traces the history of power generation with nuclear fission and ends on an open question as to how these casks and other waste will be dealt with by the NRC.”

‘We’ve got to get this in front of the governor’

For now, the students’ proposals are just that—proposals. They exist only in the context of a classroom. There was, however, a natural excitement when the students presented their finished work. There’s hope that the right set of eyes is all it would take to make a new life for Indian Point possible.

“In the final review, there was a lot of enthusiasm about the project that proposed to transform the site into a museum of nuclear power. The idea was simple and powerful enough to seem truly possible. The most excited of the reviewers even said, ‘we need to get this in front of the governor,’” said Molloy.

He also recalled a conversation with Richard Burroni, vice president of the Holtec site.

While touring the facility, Burroni talked about plans for the site, including removing the buildings. The vice president was then asked— what if the buildings were kept? He responded, according to Molloy, by asking, “What for?” This interaction, however brief, inspired the Cornell class. They want to convince people that reusing this site is something worthwhile.

“I don’t know how many people have considered what might be a sort of whimsical, but perhaps powerful idea of keeping these buildings and giving them a new life,” said Molloy. “But maybe if it catches the right person or enough people’s attention, it could become a real conversation.”