On a rainy morning in March, with woodsmoke hovering above Depew Park, I went to visit Peekskill’s Sugar Shack. As I neared it, I could make out the words “Maple Sugar” scrawled across the back in spray paint, and a man picking through the damp debris in search of firewood. With a smile, he welcomed me into the shack. A pan of sap simmered on the wood stove, stacks of split logs waited to be burned, and the smell of smoke and sugar filled the air.

The sugar shack is where John Neering can be found most weekends, from the end of winter to spring’s first days. A science educator, gardener, father, and former Peekskill Parks Advisory board member, he conveys enthusiasm about everything from maple syrup to his “Green Team” of budding botanists at La Salle Academy, where he’s also the science department leader. I wanted to understand more about his impact in our community as well as his work at La Salle Academy in lower Manhattan.

“This Was It:” Becoming a part of Peekskill

John Neering can trace his obsession with the outdoors back to his boyhood. Growing up in suburban Grand Rapids, Michigan, he loved exploring the nearby woods and discovering the local fauna. The possibility of combining this passion for the natural world with the good work of teaching emerged when he became a volunteer teacher at La Salle Academy after earning his Masters in Education from Fordham University in the Bronx.

Twenty-two years ago, he and his wife took a look at a house tucked away in Peekskill’s Mortgage Hill neighborhood and fell in love: “I didn’t even let my wife have a chance; this was it.” Enacting boyhood dreams of working with the surrounding ecosystem rather than paving it over, he and his family installed organic gardens and later, a pond. Neering’s Instagram, @neeringsciencenerd, depicts his square, flat lawn and its transformation into an oasis of life, bursting with pollinator-attracting flora and protected without pesticides.

The Sugar Shack’s second act

The sugar shack is a community gathering spot, home to a series of workshops John has run since 2020. These workshops, offered by the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation, teach Peekskill families about the ancient tradition of harvesting maple sap and boiling it into maple syrup. The structure itself dates back to the 1970s, and John was instrumental in getting it back in action with another former ecologically-minded Peekskillian, Nicole Crane. In 2019, Crane and Neering pitched a renaissance of the Sugar Shack to the city, and residents were once again welcome to attend sugaring workshops.

Neering credits two Peekskill Parks Superintendents; first, Joyce Cuccia and then Cathy Montaldo with helping to get the word about the sugaring workshops out in the community. He also cited the contributions of articles in the Peekskill Herald and peekskillexurbanist.com in helping to point Peekskill residents toward this overlooked municipal gem.

In these workshops, attendees see maple sap as it first emerges, from taps or stiles pushed into the bark of sugar maple trees. (When asked if any other trees are suitable for making maple syrup, Neering explains, “You get less bang for your buck. There’s more water, less sugar as you go down the line: sugar maple, black maple, and all the other maples, [even] Norway maple.”) The towering sugar maples exude a sense of permanence; their bark is craggy and green with lichen. Their limbs make jagged, dendritic lines high into the sky, but the easiest way to identify them is by the metal buckets they wear, complete with hat-like lids to keep debris and precipitation from spoiling the sap.

Back inside the shack, we’re invited to try the sap. It’s just been passed through a screen, and will then be added to the large open pan on top of the stove that crackles as Neering adds branches. Its taste is quickening, and I’m reminded of Neering’s allusion to the history of maple-tapping in Norway, how tasting the first run of sap was a seasonal rite. This watery substance is truly the tree’s lifeblood, running to get its photosynthesis factories online in the form of leaves. To drink it is to celebrate the ending of another winter and the promise of this year’s growth.

Sugaring is temperature dependent: sap can only flow up from the roots when the days are above 32℉ and the nighttime mercury falls below freezing. The best sap harvest occurs during temperate days and cool nights, usually in February and March in our region. Because climate change has recently resulted in irregular temperatures, Neering has started tapping for sap in late January.

Maple syrup is famous for being arduous to distill. Neering reminds me and other attendees that forty gallons of sap results in one gallon of syrup. Forty buckets of what is mostly water can quickly overrun the collection buckets: “No tours are given during the week, but the sap doesn’t stop flowing.” Neering, whose teaching appointment in the city means longer commutes, was able to stay on top of the demanding sap-management schedule by enlisting local help: his son was a senior at Peekskill High School and was able to arrange an internship where he and a friend stewarded the sap, storing it in containers in the shack until the weekend when John was able to simmer it down. He also relies on neighbors but occasionally has to venture into the woods after dark to harvest sap by headlamp.

Neering relies on family and friends to make this ancient tradition possible, just as Native American regional tribes would turn whole villages into “sugar camps” close to the trees that provided this prized and portable source of calories. This sweet, hard-won distillate of the land requires community; in the case of this quirky addition to the Peekskill Parks offerings, Parks Department delivers literal fuel in the form of plentiful ash stumps. Neering says the wood is “delicious” to boil sap with, steadily and intensely hot, but reveals another somber ecological story. Ash stumps are so plentiful because the invasive emerald ash borer has laid waste to many living trees, and still marches northward.

As my allotted interview time with Neering drew to a close, several people approached the shack. Before I knew it, I found myself in the middle of a room of neighbors-of-neighbors, sons of moms I knew through the Peekskill Garden Club, new personalities in the tapestry of our city. In reviving the sugar shack, Neering has resurrected a dearly needed third space, one with an enticing dearth of technology. In its place is the opportunity to stare into the fire, drink a little of yesterday’s rain (lightly filtered, of course, through a sugar maple), and listen to each other.

Neering’s Green Team at La Salle Academy

Neering first joined La Salle Academy in Lower Manhattan as a volunteer teacher fresh out of graduate school. Although he taught in several different positions in Virginia and New York, he never lost admiration for the hardworking Christian brothers, whose dedication to teaching is encoded in the La Sallian tradition. “I watched these brothers laboring to grade, and create papers, and I thought, ‘These guys are crazy. Let’s play cards,’ you know? And then I began to realize, you have to work to be a teacher. And I thanked them for showing me that.”

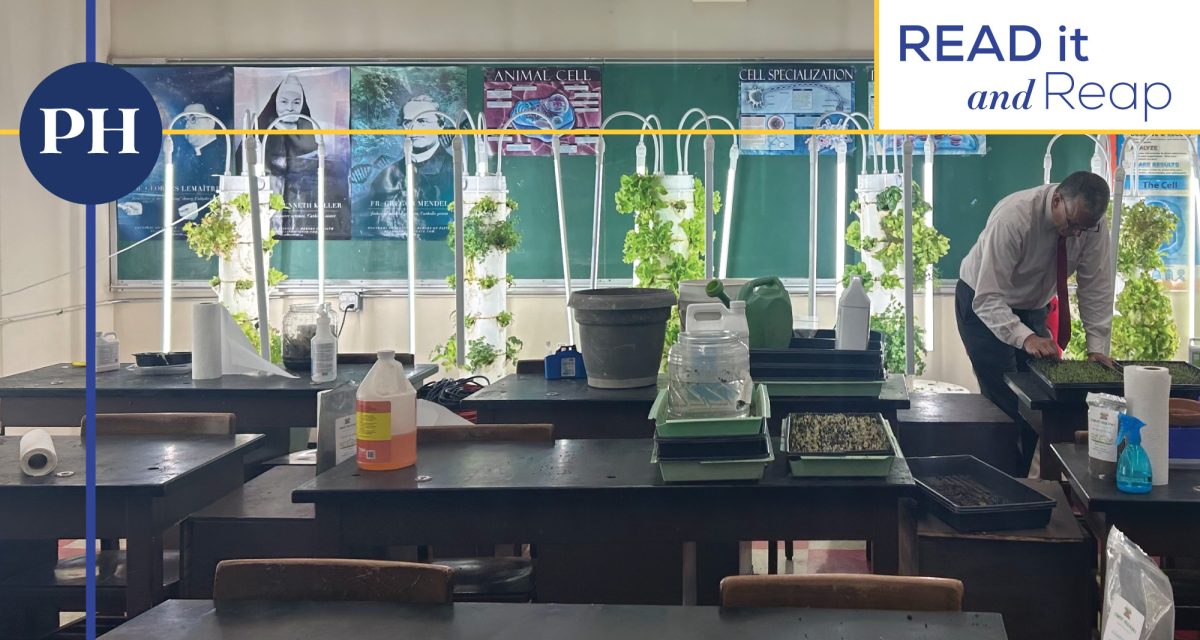

Coming back to La Salle in 2018, Neering felt as though he had a second chance to enact all of the hard work he had committed to in the time between that revelation and his stints working in public school districts in Virginia, and Hastings, Pelham, and Scarsdale. With renewed purpose, he held his students to high standards and created inroads for deeper exploration into biology, chemistry, and the marketplace. As science department leader, he unwittingly inherited responsibility for the four hydroponic grow towers someone had thought were a good idea to purchase. Ever the willing gardener, Neering took it on, calling the student stewards of the towers his “Green Team.”

Fast forward six years, and Neering’s Instagram account provides evidence that those grow towers have been put to good use. In one video, three proud Green Team members gently nod their heads as if to say, “We know you’re impressed,” as they display bins stacked with vibrant lettuce and herbs, all grown within the school, with nutrients specially administered by Green Team members. The team grows enough to donate to local restaurants and charities, at any time of the year.

Neering ensures that Green Team members appreciate the economics of providing their goods; at a selling price of $38 for half a pound of micro cilantro, the three pounds they harvest for participating restaurant Cooper’s Craft and Cocktail earns them the right to boast. In addition to the restaurant, the Green Team grows, donates and delivers greens to Visions Services for the Blind and Visually Impaired at Selis Manor and Good Companion Senior Center.

Today the Green Team, about twenty teenage boys, cares assiduously for this indoor farm, attending to nine hydroponic grow towers. These towers, essentially souped-up water pumps, use porous “rock wool” saturated with nutrient-augmented water rather than soil for their growing needs, and have lighting strips integrated. These grow towers are deployed by the Green Team year-round. Members sow seeds for tender greens like mizuna, Grand Rapids and Red Rosa lettuce, and cilantro. They monitor water levels, add nutrients when necessary, repair the towers when they break, judge when to transplant germinated seeds, and coordinate harvests and delivery.

Neering talks about how the smell of cut cilantro can lure passersby into his classroom: “People who are in the hallway will say, ‘What is going on down there? We can smell cilantro!’ Yeah, for 100 feet, you can smell it!” The immediacy of the scent of this herb, even the sound of dripping water in his classroom, gives students access to a greener world, and he rejoices in having the Green Team as an outlet for that interest.

Neering has produced bushels of greens at La Salle, but exploring eco-conscious gardening is its own payoff. Among the lessons; the value of patience, as well as more concrete revelations: “I’ve learned that New York City can provide fresh produce to itself by doing this. It’s totally possible. Every roof could become a garden. We could make green roofs, and we could put a greenhouse on the roof, and you could feed the whole building.”

What’s next for Neering

John Neering will be awarded the La Sallian Educator of the Year Award at La Salle Academy’s annual gala on Thursday, May 8th.

When asked what his next big adventure is, he discussed the exciting prospect of a greenhouse on the site of the planned new La Salle Academy. This could extend the Green Team’s territory into growing tomatoes, which are difficult to produce on grow towers. He also talked about the prospect of growing in soil created by composting by-products of the grow tower’s bounty. “I would love to just crank out not only hydroponic, but then soil-based things too. We make soil at school. The compost… it’s unbelievable. I showed the students, and they were like, ‘Man, this is nasty.’ The other day, I had a kid smell that same drum and he goes, ‘There’s no smell.’ It’s this black, rich soil, you know.”

This alchemy, from something forgotten, nasty, and flat to something inviting, challenging, sustaining – these are the opportunities Neering makes for the organisms around him, from the invertebrates in his homemade pond to the students he teaches, a true gardener of minds as well as the land.

Join more of Peekskill’s gardeners at the Peekskill Garden Club’s Annual Plant Sale on Saturday, May 10 at the Peekskill Waterfront!