Updated November 7, 2024: The original story had 19 participants. As a result of this article, 6 additional participants reached out and added their addresses to be included. The embedded map has been updated towards the bottom of the article.

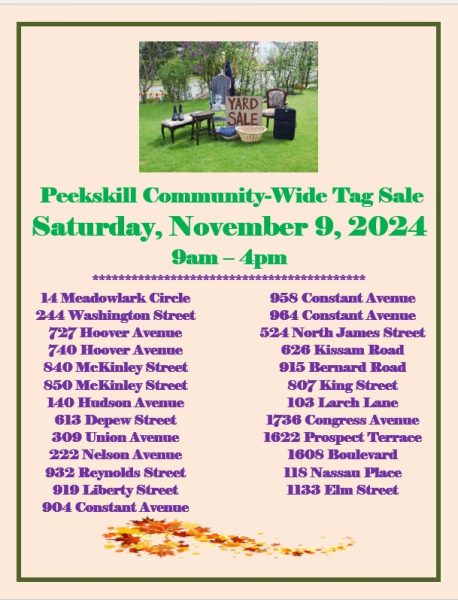

Before shopping all those corporate stores, and just in time for the holiday’s, shop your friends and neighbors tag sales right here in Peekskill at the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale and see what treasures you may find. From books to dishes, glassware and furniture, and legos to teddy bears, your friends and neighbors have it all. Looking for a chandelier? Your neighbor may be selling one. Is it a table you are looking for? Your neighbor may have one. Dresser? Board games? Holiday decor? Figurines? Dog crate? Pots and pans or bakeware? Picture frames? Planters? Clothes? Purses or wallets? Garden tools? Video games? Kitchen appliances? All of them are for sale at the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale this Saturday, November 9, 2024 from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

From the Beach Shopping Center all the way down to the Blue Mountain Plaza, across the City to the Hampton Oaks Shopping Center, and everywhere in between, more than 25 friends and neighbors will be part of the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale. Help your neighbors, make new friends, say hello, keep Peekskill a friendly town, and shop for fantastic gifts that you will not be able to find anywhere else. This is a bargain shoppers galore. You never know what you will find at very reasonable prices and at prices better than any Black Friday sale you will ever see.

If you would like to add your address to the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale, simply visit their Facebook page, and add your address in the comments of the post or send them a message. But do not wait, the cut-off for signing up is this Wednesday, November 6.

The annual Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale has been in existence for over 9 years dating back to 2015. Depending on demand, some years it occurs twice, once in the Spring, in May or June, and once in the Fall, typically October or November

The Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale is an offshoot of The Peekskill Community Network – The Original Forum which just reached a milestone of 14,000 members on November 2, 2024. Founder and administrator of The Peekskill Community Network, Leslie Lawler, was asked many years ago if the Peekskill Community Network could help in some way shape or form continue a Community Wide Tag Sale that the City of Peekskill at one time hosted. Seeing the opportunity to connect the community and meet neighbors in a positive, encouraging, informal and comfortable setting, Lawler picked up on a worthwhile endeavor the community wanted to continue. Thus, the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale was reborn. Lawler has continued the tradition year after year, in addition to being the co-founder and leader of the #PeekskillCleanRoutine and the administrator and moderator of the very popular Facebook group The Peekskill Community Network – The Original Forum.

The interactive google map will help folks get from tag sale to tag sale. You can also click on each address below to get directions to each tag sale.

- 14 Meadowlark Circle

- 244 Washington Street

- 727 Hoover Avenue

- 850 McKinley Street

- 140 Hudson Avenue

- 613 Depew Street

- 309 Union Avenue

- 932 Reynolds Street

- 919 Liberty Street

- 904 Constant Avenue

- 958 Constant Avenue

- 964 Constant Avenue

- 626 Kissam Road

- 807 King Street

- 103 Larch Lane

- 1736 Congress Avenue

- 1622 Prospect Terrace

- 1608 Boulevard

- 1133 Elm Street

Don’t forget to tell everyone at each of the tag sales you visit, you read about the Peekskill Community Wide Tag Sale in the Peekskill Herald.

November is the Peekskill Herald’s big annual fundraising campaign – where every dollar donated is matched, dollar for dollar, by major national funders through our partnership with News Match. Please help by donating to keep this 501c3 news organization thriving.

Visit the Peekskill Herald Events Calendar Features and the Peekskill Herald Event Calendar to see more local events. To add your event, visit the Peekskill Herald Event Calendar. Subscribe or donate to the Peekskill Herald and receive the most updated news stories to your inbox daily.