Editor’s Note: This story was reported and written by Ray DePaul, the Herald’s Newmark Journalism School intern. Funding was provided by New York Community Trust – Westchester.

Peekskill is an official “environmental justice community,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

The city has a unique set of challenges that warrant this designation, including its median income, ethnic makeup, and prevalence and multitude of several different types of pollutants.

“Within a few miles of downtown Peekskill, we have the trash incinerator, the sewage treatment plant, the BASF chemical plant, a gypsum plant, a nuclear power plant, [and] a high-pressure fracked gas pipeline system that carries a large portion of gas from Pennsylvania to New England,” said Courtney Williams, head of Westchester Alliance for Sustainable Solutions, an organization seeking to educate about the importance of adopting alternative solutions.

“Environmental justice” has many layers of meaning. For those working in government, it can be a matter of defining cut-and-dried criteria. For residents of environmental justice communities, it’s personal.

Environmental justice is defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income for the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.”

In short, environmental justice means ensuring that no particular group of people bears an undue share of the environmental impact of the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.

That’s much easier said than done.

One small example illustrates the larger point. Paul Presendieu was only four months old when his mother died after a tree fell on her in New Rochelle. At the time, the city had no tree ordinance, so there was no routine inspection of tree health in the city. In 1992, only a year after her tragic death, New Rochelle put a tree ordinance in place and has amended it since to include many issues around the care of trees.

Advocating for and getting the right policies in place is critical, and can help save lives.

Presendieu also illustrates a second point relevant to environmental justice. Now 33 years old and an environmentalist in New Rochelle, he is the chairman of New Rochelle’s Ecology and Natural Resources Advisory Committee. As the son of Colombian and Haitian immigrants, Presendieu is the only black person – and only person of color – serving as an advisory chair for New Rochelle.

Because of the low representation of affected communities in key civic roles, it can often be difficult for those working for the environment’s well-being to fully appreciate environmental justice as an intersectional issue with implications for everyone – for all communities, whatever their social, racial, or economic status.

“People are oblivious to the impact of overall structures and quality of life until it hits home,” Presendieu said.

An Environmental Justice community designation, such as Peekskill has, offers one key for tackling environmental issues within a community and educating the public about the connections.

New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, passed in 2019, requires 35 percent of State investment benefits to be directed to these “disadvantaged communities.” If adversely affected by environmental issues, such communities are known as environmental justice communities.

The state defines environmental justice areas as falling into one (or more) of three criteria. For urban areas, at least 52.42% of the population has to have reported themselves as being a member of a minority group. For rural areas, 26.28 percent must have reported themselves to be in minority groups. The final criteria states that for either urban or rural areas, 22.82 percent of households fall below the federal poverty level.

Several other factors, including proximity to facilities historically discriminatory, such as active landfills or oil storage facilities, and potential climate change risks and potential pollutant exposure, are also taken into account in assigning an environmental justice designation,

Environmental justice communities are home to residents who often go overlooked in local, statewide, or even national legislation.

The city of Peekskill has often also been referred to as “financially struggling,” in part due to having a median household income significantly lower than that of surrounding communities, according to 2022 American Community Survey 5-year estimates.

Presendieu said Peekskill’s pollution data is worse than 98 percent of municipalities across the state. “How that hasn’t called for a climate emergency or state of emergency where a robust Task Force is put together just shows the level of disconnect that our government leaders have,” he commented.

A large part of the environmental burden may be due to the trash-burning plant Win Waste, formerly known as Wheelabrator Westchester, but there are others. A 2010 environmental justice inventory for Peekskill cites its major sources of air pollution as including BASF Corporation, Wheelabrator Westchester, and Lafarge North America, with additional sources from Indian Point and Lovett Generating Station (closed). These facilities emit nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, sulfur dioxide, and other hazardous air pollutants.

The 2010 comprehensive report, Community-Based Environmental Inventory for the City of Peekskill (cover shown above), was prepared by the Peekskill Environmental Justice Council in partnership with Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc. and Citizens for Equal Environmental Protection. It describes in detail the community and key sources of local water and air pollution, land use (e.g., roads, highways, traffic, marinas, boating), and related health issues.

What Peekskill residents say today

Peekskill public housing residents shared several current scenarios illustrating environmental justice issues with this reporter.

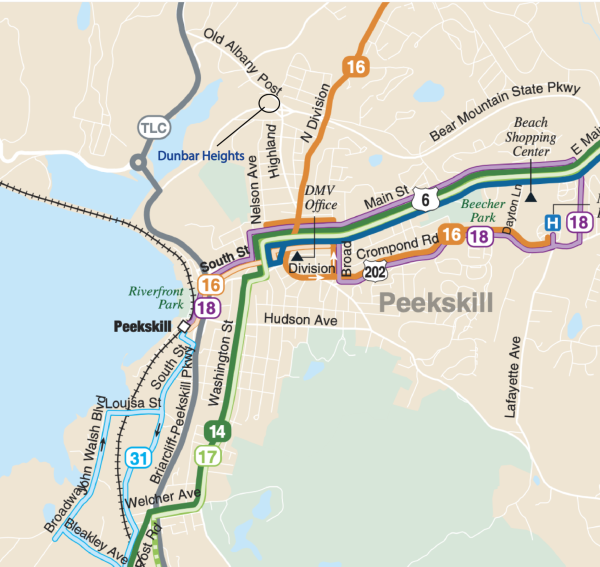

Dunbar Heights on Highland Avenue and Bohlmann Towers on Main Street, two public housing developments in Peekskill share certain similarities to the Bronx’s notorious “asthma alley.” The inhabitants are primarily minorities and or low-income.

Dunbar was converted into public housing in the mid 1960’s. Peekskill’s wastewater treatment plant is right below the complex and the stench of chemicals often wafts uphill into resident’s homes.

“[The residents] can smell [it] sometimes, and when they do, they’re supposed to call the phone number of the plant” said Tina Volz-Bongar, an organizer within the Tenants Home Association. “That plant should be monitoring itself and it shouldn’t be up to the tenants who got stuck with this thing that’s for the entire city right next to them.”

Beyond the smell itself, the significant presence of air pollutants has led some residents to believe that the pollution may cause illness. The main diseases residents and other stakeholders cited were cancer and asthma.

A 62-year-old prior resident of both Dunbar and Bolhmann who wished not to be identified claimed both of these illnesses were all too common.

“My daughter is suffering now from some kind of unknown respiratory problem,” she said. “Kids as young as five or six years old have asthma. One out of three people [who live in either housing development] had some kind of asthma, some kind of bronchitis, some kind of lung infection, some kind of suffering.”

Environmental justice also extends to transportation issues. Highland Avenue has no bus stop close to either of the housing developments. For most low-income residents, this can exacerbate how far they must commute for their jobs.

The nearest bus stop is on North Division Street, a 10-minute walk from Dunbar Heights. Walking to Peekskill Middle School would take around 30 minutes, a trek most of the children living in the developments must do daily during the school year.

Even when created to promote green initiatives, projects surrounding housing developments can still cause harm under the guise of benefits. “Many times jobs are offered at the expense of further pollution,” said Melissa Checker, a professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York who studies environmental science through the lens of environmental justice. “[Pipeline projects] kind of usually end up going through areas that already are suffering from a lot of pollution or are dealing with a lot of issues of toxicity.”

A broader view of challenges to environmental justice

Checker said lack of proper representation at the right places can lead to NIMBY – “not in my backyard” – situations.

“Often, the people advocating hard to not have [a] project go anywhere near their area are the ones that have more resources and political clout; they can show up to meetings to fight against [a project],” said Checker. After receiving such pushback, companies often put their projects where people are less able to advocate for an alternative. This can create a cycle of environmental racism. “Asthma alley” in the Bronx is an example. Asthma rates in Mott Haven are five times higher than the national average and 21 times higher than other neighborhoods, according to 2019 reporting from The Guardian.

In the United States, exposure to air pollution is disproportionately experienced by a non-white majority and inhaled primarily by Hispanic and Black populations, according to a 2019 study. The “excess exposure” experienced by the aforementioned ethnic groups is around 56 and 63 percent, respectively.

Checker said that communities with “undue numbers” of environmental burdens could be subject to further complications. These burdens can include health issues for a particularly vulnerable population, restricted availability of public transportation and lack of access to quality health care.

A specific kind of disruption can take the form of transformer stations. These stations convert energy from high power to lower voltages needed to power homes.

“The location of [electrical transformer stations] also could be in dense areas, which are what we would consider disadvantaged communities or environmental justice communities, meaning they already have these kinds of issues going on,” she said.

“Let’s face it, who’s going to want a transformer station in their neighborhood? Nobody does. So often, they go where there is perceived to be the least resistance,” said Checker.

Having the designation of an environmental justice community opens the door for funding to mitigate the impacts on those who live here. Some Peekskill residents are taking action by submitting proposals for the 2024 Environmental Justice Data Fund, which provides funding for underserved communities to address “environmental hazards,” with importance stressed on issues of air and water quality. The fund was created by Google and is sponsored by the Windward Fund, a public charity that “incubates and hosts initiatives” seeking to find solutions to various environmental challenges. Proposals are being accepted through August 30.