Creating Scholars in Elementary School

September 13, 2022

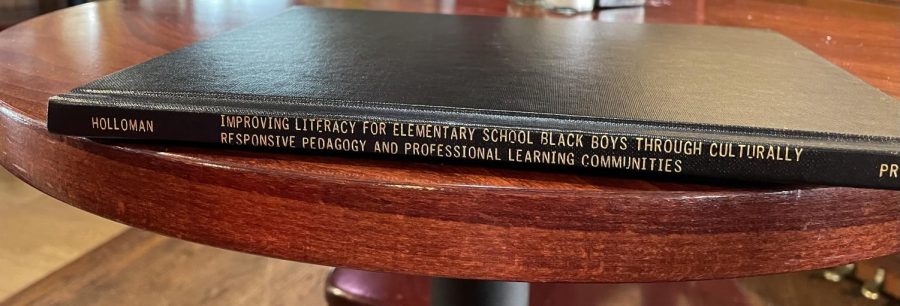

The thin, hard covered book that Bridget Holloman carries around in her purse holds the key to a way of teaching Black boys that can unlock their future as contributing members of society. The book is her doctoral dissertation.

Holloman, who received her educational doctorate degree from Fordham University in May, is leaving the elementary school classroom after 22 years for a new position as the district’s Interim Parent, Family and Community Liaison, working out of the Peekskill City School District’s Family Resource Center on South Division Street.

“I may not be standing in front of the scholars, but they will be seeing me. I will still be connected to the families,” said Holloman, 51, about her new role.

She’s aptly qualified for the position because of the work she’s pioneered during the last six years with her students and parents at Oakside Elementary. While in the Future School Leaders program that she was invited by the school district to attend, she heard the term “culturally responsive education.” She realized that term was giving a name to what she was practicing in the classroom. She graduated from the Leadership program in May of 2017, and four months later she enrolled in the doctorate program at Fordham.

“People told me once you were in the Future Leaders program, you would be wanting more. I always knew I wanted to get a doctorate, but wanting to do it and actually doing it are two very different things, like apples and oranges,” said Holloman. “I knew I needed to be an advocate and if I was going to be the advocate, I needed to have the doctorate.

Holloman, who graduated from Peekskill High School in 1989, credits her cheerleading coach, Mrs. Carlos Butler, as someone who inspired her. “She was more than a cheerleading coach,” said Holloman.

The second component of her dissertation focuses on the professional learning communities she led with five other teachers at Oakside. Once a week the five teachers met during their lesson preparation time to learn from Holloman what culturally responsive teaching practices look like in the classroom. The group read two seminal works Holloman introduced them to: “The Brilliance of Black Boys” by Brian Wright, and “Culturally Responsive Education and the Brain” by Zorita Hammond.

“We discussed how culturally responsive education means bringing the language, culture and backgrounds of the scholars in front of us into the classroom,” said Holloman. “We don’t celebrate a Hispanic person like Sonya Sotamayer just in September and October, or Thurgood Marshall only in February during Black History Month,” she said. In her classroom those people, and information about them, were woven into the fabric of the classroom every day throughout the year.

An integral component of those professional learning community sessions with teachers involved listening to each other about their backgrounds and to hear their experiences. ”If we’re honest, we teach from our experiences,” explained Holloman. The teachers in her sessions volunteered for the chance to join.

During their weekly sessions, they concentrated on the intentionality of culturally responsive education, for example, using the term ‘scholars’ when speaking and referring to students. “Scholars, more so than children or students, implies that ‘you’re smart.’ It is intentionally leading you to higher heights,” explained Holloman.

When second and third grade scholars walked into Holloman’s classroom every day, they introduced themselves to her by saying: ‘I am [name], I am a blessing to my teacher and my family. I am ready for a great day of learning.”

She invited Peekskill City Judge Reginald Jackson to the classroom for a visit and he arrived wearing his judicial robes. “One of my scholars presented him to the class,” recalled Holloman. Later, one of her scholars met Judge Jackson outside the classroom and introduced himself to the Judge as one of Ms. Holloman’s scholars.

Leading communities is what Holloman does best. She began inviting parents to monthly meetings where she spelled out what was expected of them in partnering with her in the education of their children. “I’d give them the statistics and tell them, ‘one in three black children land in jail, one in six Hispanic children land in jail, and one in 17 of white children land in jail. What group do you want your child to be in?’” She assigned parents homework and made herself available to them, giving out her cell number and calling to find out why a parent missed a meeting. If she couldn’t reach a parent of a scholar, she’d track down a grandparent. “If you want to move the needle, you have to be available” is her motto.

In first and second grade, she introduced her students to the idea that they could become Harvard Scholars. She played videos during the first week of school featuring former students who graduated from Peekskill High School in the top of their class and went on to prestigious universities. She showed a video about her nephew who is a cadet at West Point. She referred to her students as Harvard Scholars and motivated the parents to support the idea. Parents did the research and planning, and with the financial assistance of Holloman’s church community, they chartered a bus and on a Saturday went to Harvard for a tour. They did the same thing at Columbia University, and took a trip to the Museum of Natural History in New York, all organized by parents. If a parent didn’t have English as a first language, she would pair that parent with someone who could interpret for them. “That created a bonding experience for the parents,” explained Holloman.

The goal of her new position is to look at the big picture and the population the district serves. “I ask myself, ‘Are we meeting their needs?’ My job is to empower parents, to help them understand the school system, giving them a voice in their child’s education and help them be proactive. My job is to lift them up and carry them and have courageous conversations with them.”