Hiding in Plain Sight

Emma Beach and the Art of Camouflage

October 7, 2021

Today, camouflage patterns are considered as much a fashion statement as a means of keeping our armed forces concealed and safe while deceiving the enemy. Yet there was a time when this idea was an innovative concept, and a young woman from Brooklyn and Peekskill was part of a landmark treatise on the subject.

Emma Beach Thayer (1849-1924) was born Emeline Buckingham Beach, eldest of the four children of Moses Sperry Beach, publisher of the New York Sun. Around 1870 Beach purchased the land adjoining the Peekskill farm of his Brooklyn friend and neighbor Henry Ward Beecher and named it “The Beeches.” It is the Beach family for which the shopping center on Main Street is named.

Emma studied art at Cooper Union in New York City and was known for her nature studies and floral paintings. She maintained a friendship with a classmate, Kate Bloede, who married Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849-1921) in 1875. Thayer was one of the preeminent American painters at the turn of the 20th century and a renowned naturalist and wildlife advocate. Emma was a close friend of the couple and assisted them for years. She helped during Kate’s bouts with depression. After Kate’s death, in 1891, she became Thayer’s second wife, joining him in rural New Hampshire and becoming stepmother to his three children.

There, she assisted her husband in illustrating his theories of concealment for his groundbreaking and thought-provoking work on wildlife and animal camouflage Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom (1909). It was published with his son Gerald and illustrated by Abbot Thayer, Gerald Thayer, Emma Beach Thayer, and others.

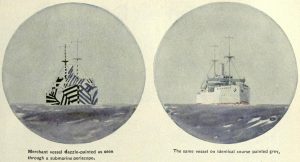

Thayer’s three major concepts in camouflage were countershading (a.k.a. Thayer’s Law), background blending, and disruptive patterns, later known as “razzle-dazzle,” often using a combination of them in practice. These were schemes that helped both predator and prey.

In explaining countershading, he claimed that: ‘Animals are painted by nature, darkest on those parts that tend to be the most lighted by the sky’s light, and vice versa,’ which made them more difficult to see.

Utilizing countershading and background blending made animals like the rabbit more difficult to see. One of the examples from the book is Emma and Gerald H. Thayer’s 1904 study, The Cotton-Tail Rabbit among Dry Grasses and Leaves, where potential prey seems to disappear against the background of its natural habitat. The image is featured above.

Other examples of background blending are these depictions of caterpillars, blending into the leaves they were eating so that predatory birds would ignore them.

Thayer and fellow artist George de Forest Bush suggested that disruptive patterns and countershading could be used for protective coloring on U.S. ships. He pitched the idea of disruptive or Dazzle coloring to the Allied powers during World War 1. The British were working on ideas of their own, but the French took it up in time for WW1 and came up with the word “camouflage,” a derivation of the French word camoufler, “to disguise, deceive.”

Dazzle paint schemes were widely used during World Wars I and II as they made it more difficult for enemy submarines to judge speed, course, and range.

In later years Thayer suffered from panic attacks and what is now known as bipolar disorder. Emma took over his correspondence regarding sales and exhibition of his artworks and worked on a book of his letters.

After Abbott Thayer died, Emma returned to Peekskill to live at The Beeches with her sisters Ella and Violet. She died in Peekskill on March 1, 1924, at the age of 74, and was buried in Hillside Cemetery.

Now, this is all to say nothing about her relationship with Mark Twain. But that is a story for another time.

Kirk Moldoff, a professional medical illustrator, has been researching Peekskill history for over three decades and has lectured extensively on the rich history of this area.