Leer en Espanol

With the changing of the guard in Peekskill’s top position in the Department of Public Works, there’s been lots of conversation around the litter problem in Peekskill. Known as a “quality of life” issue, it’s the subject of campaign rhetoric and social media posts. Peekskill could take a page from its sister city, Cuenca, Ecuador, in addressing the subject.

Creativity, logistical ingenuity and vision are foundational to Cuenca, Ecuador’s designation as one of the cleanest cities in the world.

Narrow streets made of 500-year-old cobblestone are unforgiving when it comes to large, heavy machinery that other cities employ to keep their streetscapes tidy.

Cuenca city leaders found a non-mechanical way to navigate the central business district known as “El Centro,” along with residential routes. Hiring people to walk the streets, in eight-hour shifts, with uniforms and tools to facilitate picking up litter, began some 25 years ago with the formation of EMAC, a municipal organization that is responsible for keeping the city’s 235 parks green and the 1.6 square miles of the city’s green spaces clean.

EMAC (Empresa Municipal de Aseo Cuenca, translated to Municipal Company of Cuenca Area) was founded to serve Cuenca through comprehensive solid waste and green space management, aiming to achieve a healthy, green, circular and environmentally conscious city.

That ambitious mission is guided by the vision “to be a sustainable regional company, a Latin American model for comprehensive solid waste and green space management, that innovates by continuously promoting economic circularity, environmental sustainability, and resilience to climate change.”

EMAC is directed by Maria Caridad Vazquez, who has been at the helm for two years, after working in the city’s planning division for seven years. She holds an MBA in enterprise business in the public sector. In an interview with Peekskill Herald on March 21, 2025, she explained EMAC’s $30 million budget is funded by taxes from a surcharge on electric bills and a surcharge on landline telephone usage. However, with the arrival of cell phones and the decline of landlines, that revenue stream has been decreasing steadily during the past 10 years.

In the coming year, EMAC is expected to institute a new tax on property owners who are landlords to replace the diminishing revenue from landline telephones. Vazquez explained that researchers at the University of Cuenca are formulating a business plan for EMAC on how best to implement a property tax.

EMAC employs some 330 people, which accounts for $2 million of the overall $30 million dedicated to garbage pickup and management of the parks. Of the 330 employees of EMAC, 190 are dedicated to riding garbage trucks that pick up bagged garbage and sorting it once it’s picked up. The remaining 140 people are in administration, which includes technical and operations employees.

The guiding principle of EMAC found in their vision statement focuses on continuously promoting economic circularity.

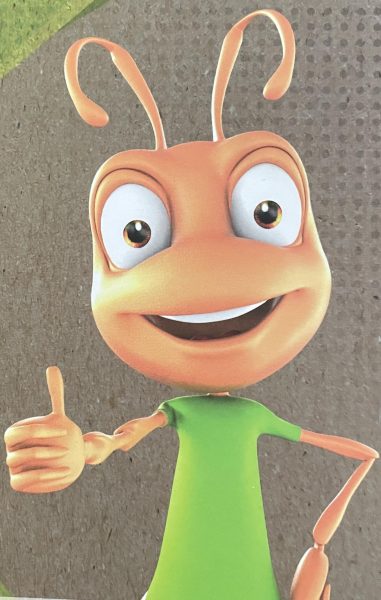

A cornerstone of that vision is education. And that education starts in the elementary schools of Cuenca, where 18 years ago the non-profit foundation associated with EMAC sponsored a public contest to create a mascot for the street sweepers. An architect won by creating the little green ant who is very clean and knows how to work on a team.

He helps educate in the schools through a magazine geared to children and funded by the educational foundation and businesses. Every year the subject changes around the concept of responsibility to keep Cuenca clean.

The street sweepers wear the green uniforms, while those who recycle wear blue and are part of a national organization with which EMAC has a financial relationship. Nearly all the 200 recyclers who collect and repurpose plastic and paper are women.