A long road stands between Manuel and his dream of becoming a U.S. citizen. He moves forward, though not as fast as he would like.

He has a work permit, a Social Security number, a driver’s license and pays taxes – perhaps everything the average American citizen does. Yet, for him, not having a blue passport makes him a stranger.

He is Ecuadorian, 42 years old, and the father of three children. The youngest was only two when they crossed the Rio Grande and surrendered to immigration authorities in Texas, seeking asylum, almost three years ago, in 2022. Some time later, they arrived in Peekskill to settle.

An attorney is handling his case. Manuel has never missed a court hearing and complies with the law.

“The first thing my lawyer advised me was to stay away from trouble – no alcohol, no parties,” he said. “My life is about working hard to move forward.”

In Limbo

A few months ago, the path to citizenship seemed shorter for Manuel.It had been suggested his asylum request might be approved after a year, allowing him to become a resident and, five years later, a citizen.

Now, there are no guarantees. The new administration of United States President Donald Trump and its immigration policies are placing obstacles in the way. In court, a judge could request further evidence regarding the reasons for seeking asylum, deny the case, and, as a result, the immigrant would have to appeal. Moreover, with the recent changes in the law, Manuel might never even make it to court and could receive a deportation order outright. Anything can happen.

“Doing things the right way comes at a high financial cost,” he explained. “I spent $10,000 just to start my case and obtain my work permit.”

Going to court to present his asylum request will cost him several thousand dollars more – that is, if no complications arise.

“I have tried to handle the process on my own, but I don’t speak English,” Manuel said. “And I fear filling out a form incorrectly and seeing all my efforts go to waste.”

He acknowledges that immigration agencies’ digital platforms are fairly clear and user-friendly. However, his lack of knowledge about immigration law and the language barrier have led him to seek legal guidance.

Manuel strives to integrate into the country. Twice a week, he attends English classes at the local library. At times, he feels that his age prevents him from learning as quickly as his children, who have a clear advantage.

“They go with me whenever I need to handle paperwork,” he said. “People think migration is only difficult until you reach your destination, but they forget about the daily challenges.”

Living in the Shadows

Unlike Manuel, Ana has been unable to legalize her status in the country.

There is no official record of her anywhere. She has lived “in the shadows” for more than four years and now fears deportation, especially as anti-immigrant policies have intensified and the Department of Homeland Security has announced the implementation of a digital platform to register undocumented individuals.

Anyone over the age of 14 without proper documentation must register in the system. Failure to do so could result in fines or up to six months in jail.

The mere thought of it terrifies her. “I work in cleaning. I get paid in cash. I don’t have a bank account. I have tried not to leave any trace of myself anywhere. I have never been to a hospital, I don’t have a driver’s license, nor any identification except for the one from my home country [Mexico],” she explained.

Those “precautions” to remain undetected may have been in vain. “When I first arrived, I went to see some lawyers, but they told me I had no chance of obtaining papers,” she recalled. At that moment, she decided to be cautious and not invest in legal fees that would not guarantee a promising future.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, approximately 54,000 undocumented individuals live in Westchester County. They represent five percent of the population.

Gloria’s Hopes

On the other end of immigrant experience Gloria, holding her U.S. residency. She is just a few months away from becoming a citizen, and although the path is supposed to be smoother, she is filled with fear.

It is not the English proficiency test or the U.S. civics exam that makes her nervous, but rather the changes in regulations being implemented by the current administration.

Gloria fears that new requirements may be added or bureaucratic hurdles imposed, which could delay her process.

More than four years ago, she arrived in Peekskill after her husband’s father completed the petition process for an immediate relative. Leaving her home country (Ecuador) was not easy, but the pursuit of a better future led her to make that decision.

“This is a country full of opportunities,” Gloria said. “If you do things the right way, you can go far.”

Gloria acknowledged that she speaks from a place of privilege and that not everyone has the chance to regularize their legal status. However, for Gloria, the struggle continues as well. This is because the changes in the law proposed by the current administration could also affect her stability.

Immigration attorney talks immigration hearings, deportations

Whether it’s the road to becoming a citizen or fear of deportation, confusion surrounds the topic of immigration.

Caridad Pastor, lawyer at Pastor & Associates P.C., recommends those not entering through a regular port of entry turn themselves in as soon as possible and request a hearing before an immigration judge.

“It’s always best to come through an actual port of entry and request asylum at the port of entry,” Pastor told the Herald on Feb. 24.

The wait for a decision by a judge can vary depending on the immigration court and the volume of people who request hearings.

On the day the Herald spoke to Pastor, she was in court in New York City where individuals were scheduled to get individual asylum hearings in 2028, whereas in Detroit they usually get those hearings within six months, she explained.

Asked what misconceptions are common around the country, Pastor said people believing that undocumented people could be picked up at any time. Pastor clarified who ICE could detain.

“They’re going after people accused of crimes or with criminal convictions already,” Pastor said. “It could be any crime. It could be a small retail theft or whatever that they’re going to be called on that.”

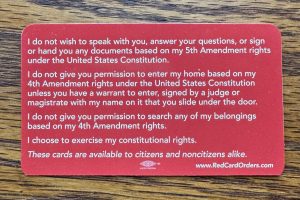

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) requires a judicial warrant signed by a federal district court judge that specifies what they’re allowed to search. According to Pastor these judicial warrants are rare.

Such a judicial warrant was why ICE visited the City of Peekskill on Jan. 31. City police said they were informed that federal agencies, including ICE, were looking for an individual with a criminal record.

Pastor, who serves clients throughout the U.S. but has not served any in Peekskill, said in her 34 years of being an attorney, she has only seen ICE serve one judicial warrant and it was because they were doing an operation in conjunction with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

“Going into somebody’s private property is obviously protected by the Constitution and judges are a little reluctant to issue those unless there is good evidence of criminal activity…” Pastor said. “Or… a person on the premises has been conducting criminal activity or is engaged in criminal activity.”

In contrast, administrative warrants are drafted by ICE, and they do not carry the same force on the law that a judicial warrant does, Pastor explained. With an administrative warrant, ICE may arrest individuals in public but not enter someone’s private home.

“You do not need to open the door or allow (ICE) on the premises,” Pastor said. “I always advise [clients[ have them slip the warrant under the door, so you’re not holding the door and there’s any confusion about whether you’re allowing them on the premises or not.”

Having permanent residency does not prevent an immigrant from being apprehended by ICE if there is an accusation of a crime, Pastor said on Feb. 24.

This was displayed last week when a Columbia University graduate and green card holder was detained by ICE in New York and transported to an immigration jail in Louisiana after helping to organize campus protests against the war in Gaza.

In the majority of cases, a detainee has the right to appear before an immigration judge so an immigration lawyer can defend their case, Pastor said. However, if an immigration judge has already ordered you deported and you have not left, you do not have a right to go before an immigration judge.

Pastor recommends clients keep “know your rights” cards to stay informed, as well as guardianship forms in the event they are deported and need to designate a guardian for their child.

“You need to be able to have that child taken care of, whether eventually that child is going to join you in the home country or not,” Pastor said. “You want to be able to have somebody that can at least take care of that child while you’re working your way through the system.”

The New York State guardian form is available and accessible in a variety of languages for both citizens and non-citizens.

![Peekskill girls volleyball in action against Fox Lane on Oct. 16. (Peekskill City School District]](https://peekskillherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Lead-photo-6-1200x640.jpg)