Westchester County crossed a milestone when the last census in 2020 revealed there are now more than one million people living here.

So, with more folks competing for a housing stock that hasn’t kept pace, the result is predictable.

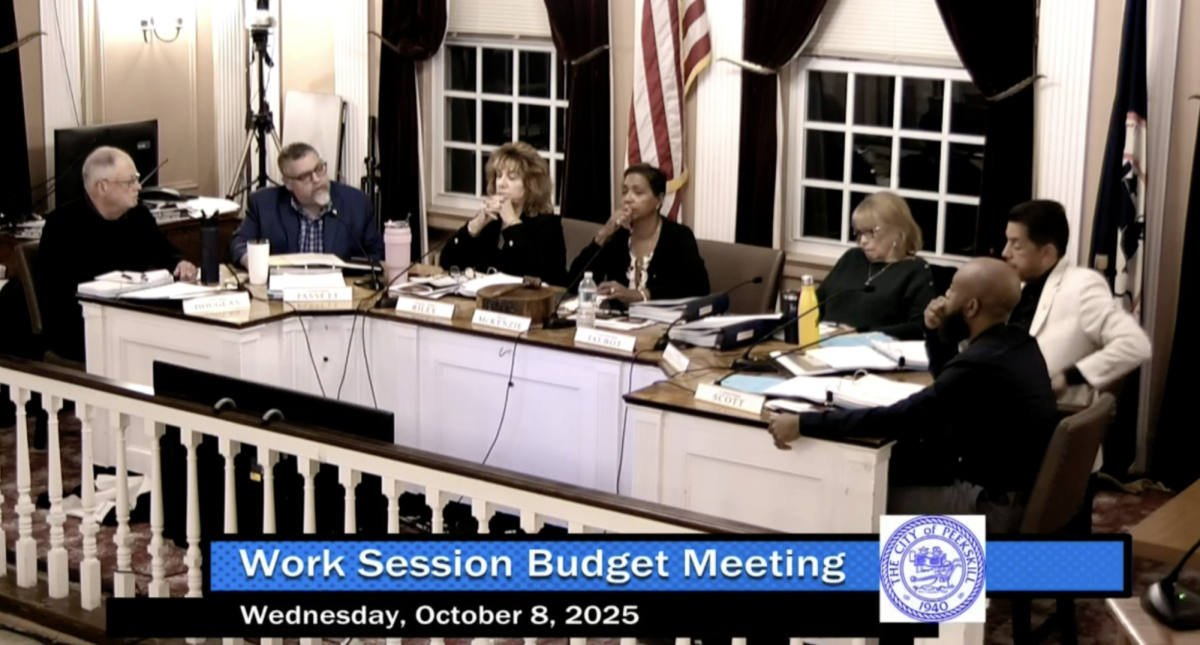

“It’s Economics 101,” Tim Foley of the Building & Realty Institute told a gathering of more than 75 at the Hudson Valley Gateway Chamber breakfast on Jan. 9

“If the supply is inadequate, the prices go sky high. In addition, with the migration up from New York City during Covid, the housing inventory shrunk and the prices went bananas.”

An assessment of the county’s housing needs published in 2019 determined that it would take 11,703 new housing units to balance out supply and demand. The Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress is updating its study and the situation is not getting better.

“The new study will show the crisis is not being abated – it’s actually worse,” Michael Romita, president and CEO of the Westchester County Association, told those at the gathering in the Peekskill Central Firehouse.

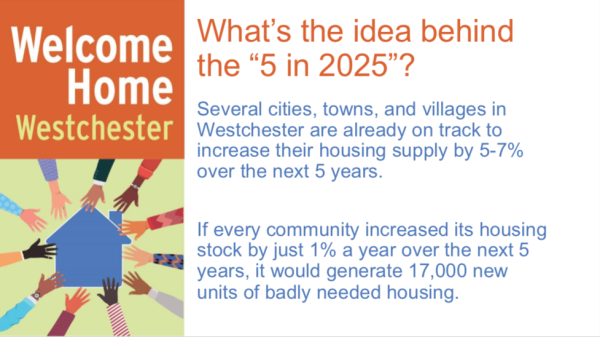

“If every community increased its housing by just 1% over the next five years, we would eclipse the needs the 2019 study determined. Not everyone needs to do the same thing, but everyone needs to do something.”

‘Five in 2025’ a housing call to action

The Building & Realty Institute (BRI) has spearheaded a “Welcome Home Westchester” campaign by uniting a wide variety of interests to shine a spotlight on barriers to new housing and ways to overcome them.

Eight different organizations make up the primary partners including the BRI, the Westchester County Association, the Construction Industry Council and Westhab.

Twenty-three other Westchester interest groups make up the Policy Advisory Committee, including Ginsburg Development, Westchester Residential Opportunities, Habitat for Humanity, Calvary Baptist Church and Caring for the Hungry and Homeless of Peekskill (CHHOP).

The “Five in 2025” initiative lays out five things communities can undertake to build a momentum for new housing construction in their city, town or village.

Completing a housing needs assessment and using state tools to become a pro-housing community can focus local officials on what needs to be done and how to fund the effort.

Creating a local fast-track environmental review process and providing training for volunteers on local planning and zoning boards can help streamline the time it takes for developers to get the sign off to build. And promoting ADUs (accessory dwelling units) and TODs (transit-oriented developments) can lead to more housing stock.

Much work to be done on local, state level

Multi-family, “affordable/workforce” housing is the primary means of addressing the Westchester housing shortage.

The high cost of living here makes “affordable” a relative term. Federal guidelines set the area median income (AMI) figure at $156,200 for a family of four. Developers who win county, state and federal low-interest financing target their projects at a lower AMI – for instance, a project at 50% of AMI would be open to an income of $78,100 maximum.

“People who struggle most to afford housing are considered middle class and not just lower,” Foley said. “The problem includes millennials, recent retirees and people who want to move here.

“Nearly as many people are coming into Westchester to work from somewhere else farther away with cheaper housing prices than are going into New York City to work – that’s a problem.”

Losing a generation of young families due to out-of-control housing costs has long-term implications for Westchester’s vitality.

“Our fastest shrinking demographic is the 30 to 45 year old, down for two successive censuses,” Foley said. “That’s a giant red flag because that is how we have always revitalized our communities, through working young families coming here, living here, putting their kids in our schools, becoming local customers. If we’re losing that demographic that’s a bad sign for our region as a whole.”

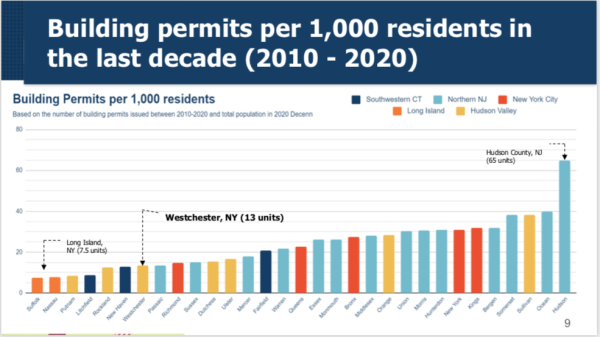

Comparing building permits issued from 2010 to 2020 throughout the tri-state region shows Westchester lagging far behind. “We would be the poster child for the housing shortage, but luckily we always have Long Island out there making us look good,” Foley said.

Hudson County in New Jersey issued permits for 65 units per 1,000 residents and Orange County, N.Y. issued permits for 28, while Westchester issued 13. Suffolk County, Nassau County and Putnam County issued permits for 7.5 units. In 2023, Wilder-Balter completed “645 Main,” an 82-unit affordable housing building in Peekskill.

One change Welcome Home Westchester advocates is a streamlining of local environmental reviews. “Even modest, sustainable housing projects are often subjected to lengthy and unpredictable reviews under the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR). Whether through inefficiency or local intransigence, these reviews can take months to years, sometimes without legitimacy,” according to the “Five in 2025” proposal.

The battle of state vs. local control over zoning

Action on the state level is also part of the campaign’s ongoing agenda. “We found in the last several years that trying to make change in Albany is pretty tough,” Romita said.

“The housing shortage is happening all over the country but New York is unique in a bad way – we are not stepping up to the challenge in the way that most of our peer states are doing.”

After defeat of a heavy-handed 2023 proposal by Gov. Kathy Hochul to force local communities to increase their housing stock by 3% over three years, the state has taken a “carrot” approach with grant money for infrastructure to communities that build. Peekskill stands to win $10 million in state “Momentum” money if the city can submit a viable plan to spend the money on infrastructure that brings more housing.

Foley called housing “the intersection for jobs, training, social justice issues around historic patterns, property taxes” and a solution for addressing climate change with designs using less energy more efficiently.

But local communities don’t all agree that “Build Baby, Build” is always the right answer for their residents in all circumstances. Objections to projects proposed in Peekskill include concerns over increased traffic, more demand for services and loss of open space. Members of the Planning and Zoning boards face the challenge of balancing the right of property owners to build and the desire to retain the suburban, rural character of neighborhoods. “We don’t want to become White Plains” is a familiar refrain.

In Massachusetts an aggressive push by the state to overrule local zoning is encountering loud and noisy local pushback. A law to allow higher density construction by right in transit zones has created battles in Milton and Needham with voters rejecting plans certified by the state law. The cases are now heading to court with the state suing the towns.

For Foley and the BRI, increasing the supply of housing is the solution. Overcoming the obstacles to that challenge is a mission everyone needs to embrace.

“The economic benefit to building the housing we need comes in terms of jobs, increased economic activity and more property taxes,” Foley said. “What it costs to service the new residents nine times out of ten will be a net positive with more property taxes flowing in to the benefit of everybody.

“The choices that local governments make intentionally or unintentionally contributed to the housing shortage we’re facing. Our job is to spotlight what we know works and highlight what we know doesn’t work.”