The person behind the bench

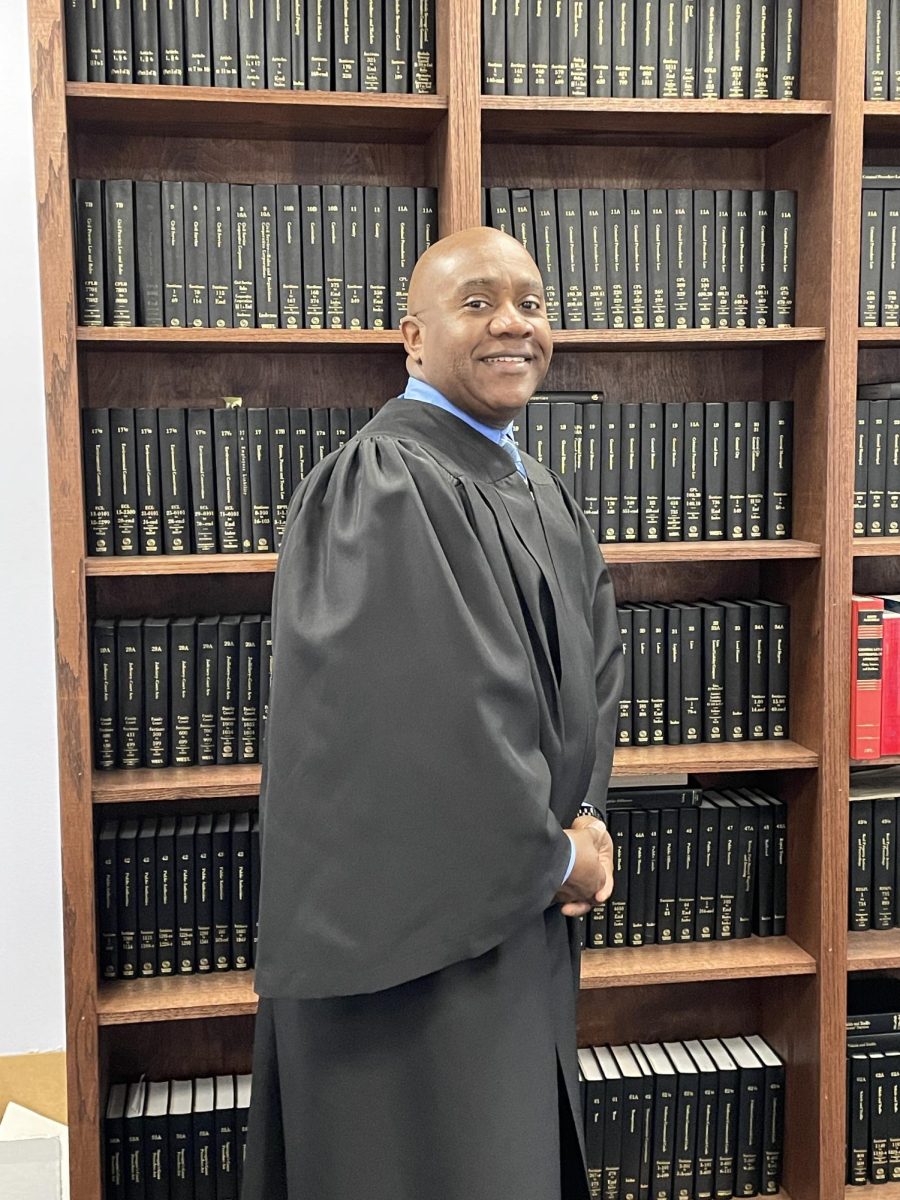

Peekskill Judge Reginald (Reggie) Johnson brings empathy gained from his lived experiences to the city court where he’s presided for the past decade. It’s a perspective guided by compassion.

Those qualities are easily discerned when watching him preside over drug court and landlord tenant issues, which have personal significance for him.

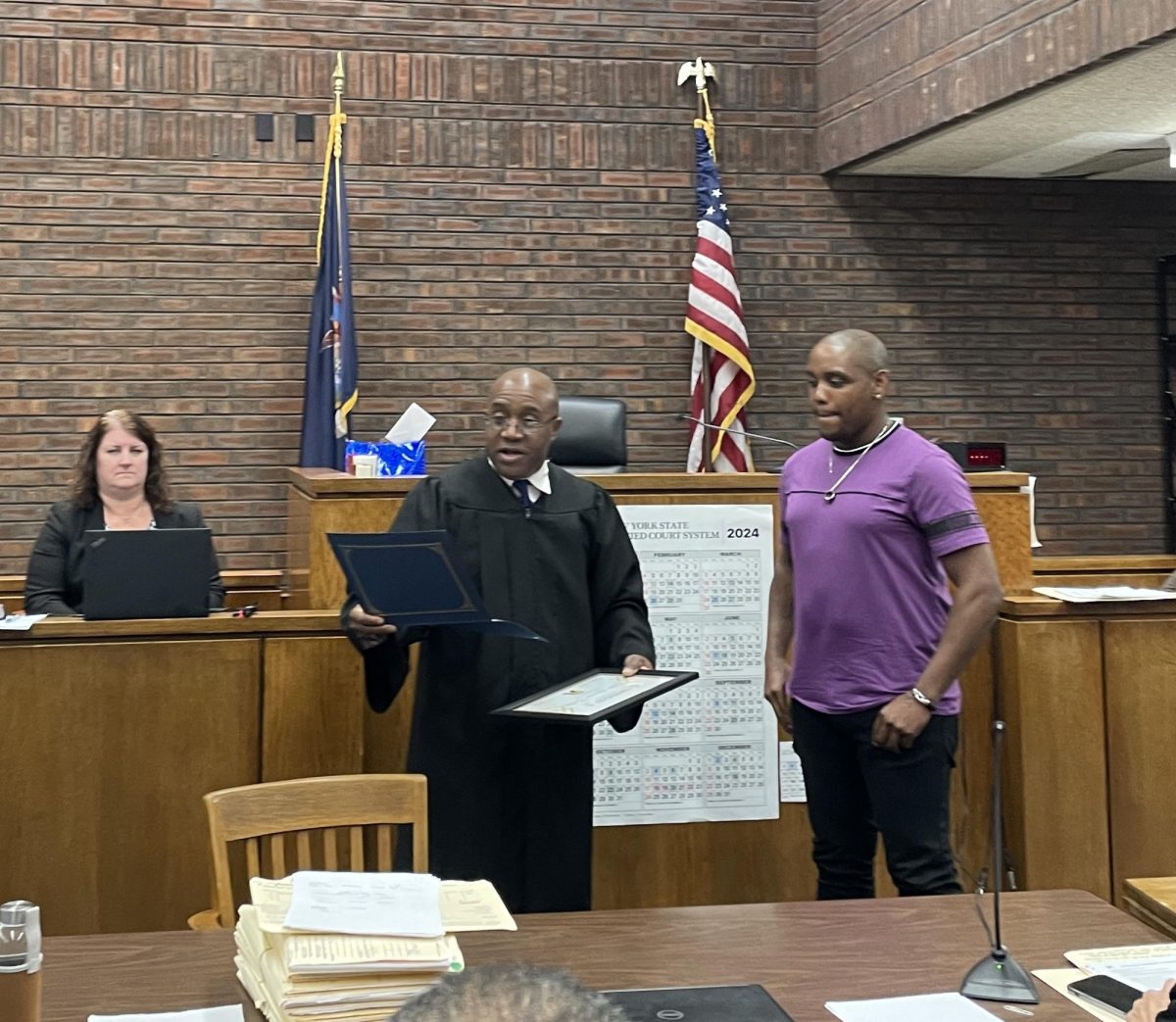

Johnson, who was recently reappointed by the Common Council to a ten-year term on the bench in Peekskill City Court, said someone in his family was addicted to drugs and he came to understand and develop empathy for people who struggle with addictions.

“It’s not just one person that is impacted, it impacts the entire family.” The fighting, stealing, and lying that accompany addiction affect everyone, especially children. That knowledge guides his behavior as he oversees drug court which is in session on the first and third Wednesday of every month.

From his decade running drug court, Johnson has gleaned that people are not the sum of their worst actions, and that motivates him to help a person be integrated into society. Participants who commit to drug court have to attend all the sessions and meet with treatment counselors when they are not in court. If they don’t fulfill these requirements, they are required to do time in jail.

On Tuesdays, Johnson presides over landlord tenant disputes. This is another area where his life experiences have shaped his judicial practices. “I have to be empathetic, because ‘there but for the grace of God go I’. I try to do whatever I can to keep people in their homes. I give them time and try to do it with humility.” When he sees single mothers trying to make ends meet he often wonders where the men are. He also stresses the impracticality to tenants who take advantage of landlords and tries to illustrate to tenants that building owners have legitimate responsibilities as well.

This subject is personal for Johnson. He recalled the time he and his wife Pamela were living in an apartment in Mt. Vernon. He was attending Pace Law School full-time and working part-time, which led them to have difficulty paying their rent. When his landlord, George N. Trikedes, now deceased, came to collect it and learned that they were struggling, Trikedes gave them time to pay and told Johnson to finish law school and make sure he graduated. It was that type of empathy and compassion that has stayed with Johnson as he listens to landlords and tenant conflicts.

-

Judge Johnson is a full time judge in Peekskill City Court.

-

Judge Johnson when he was a new lawyer.

-

Judge Johnson being sworn into office on New Year’s Day for another ten year term. His wife Pamela is reading the oath of office.

The cases that are the hardest for him to adjudicate are the criminal ones involving sexual assault of children. He notes that the violence towards immigrants who are the victims of scams and assaults, especially because they often carry large amounts of money on them, are also extremely difficult to listen to.

Growing up and attending schools in Mt. Vernon, Johnson, who is African American himself, was inspired by a high school business teacher named Milton Dudley who was the first black lawyer he’d met. Knowing Dudley started Johnson thinking that perhaps there was a career path in law he could pursue. He graduated from Hofstra University with a degree in political science and went to Pace Law School. He hung his shingle in Mt. Vernon in 1990 and ran a small general law practice performing real estate closing and personal injury law. He was also an assistant corporation counsel for the city of Mt. Vernon where he learned about municipal law. From that position, he went to Westchester County where he worked in the county attorney’s office until 2014, when he was appointed to the Peekskill’s bench.

As the full-time city judge, Johnson oversees the court administration which includes the five court officers, eight clerks, a court attorney and clerical staff along with the other functions of the courthouse including the Alternative Dispute Resolution Meditation Center for civil cases.

Johnson is also aware of court backlogs that are the result of the pandemic , and has been in discussions with fellow members of the Judges Associations to find ways to streamline some areas. Regarding traffic court, he is having conversations with the city’s corporation counsel’s office to offer pleas through the mail if the violations don’t carry points to lighten the workload of the court. As it is, every time the court is in session, two court officers need to be present at all times. If an officer is out sick or has taken another job and hasn’t been replaced, both courtrooms can’t be in session, which creates delays.

Johnson likes to say it’s not ‘his courtroom’ but rather the people’s courtroom, he just presides over it. What he’s come to realize is that for most people who come into the courtroom it’s not about a “black robe making a decision. People want their day in court to be heard.” Because oftentimes, what is resolved during a court appearance is what was offered in a non-court setting.

As much as Johnson is compassionate and empathic, he’s also pragmatic. He believes that “for most people their worst act is not what defines them.” But when he’s looking at a rap sheet, ‘you are what your rap sheet says you are,” until you can show him otherwise.

Johnson believes that everyone has the right to be defended and the district attorney has a job to prosecute. “As long as those things are working, I am going to be doing my job.”

A man convicted of a felony telling a judge how he’s learned resilience and strength from his experience in the criminal justice system is rare.

But for Brian Bailey that’s exactly what happened in the Peekskill City Drug Treatment Court (PCDTC). Drug court gave him the tools to turn his life around after his arrest and conviction on drug charges in Peekskill and Ossining in May of last year.

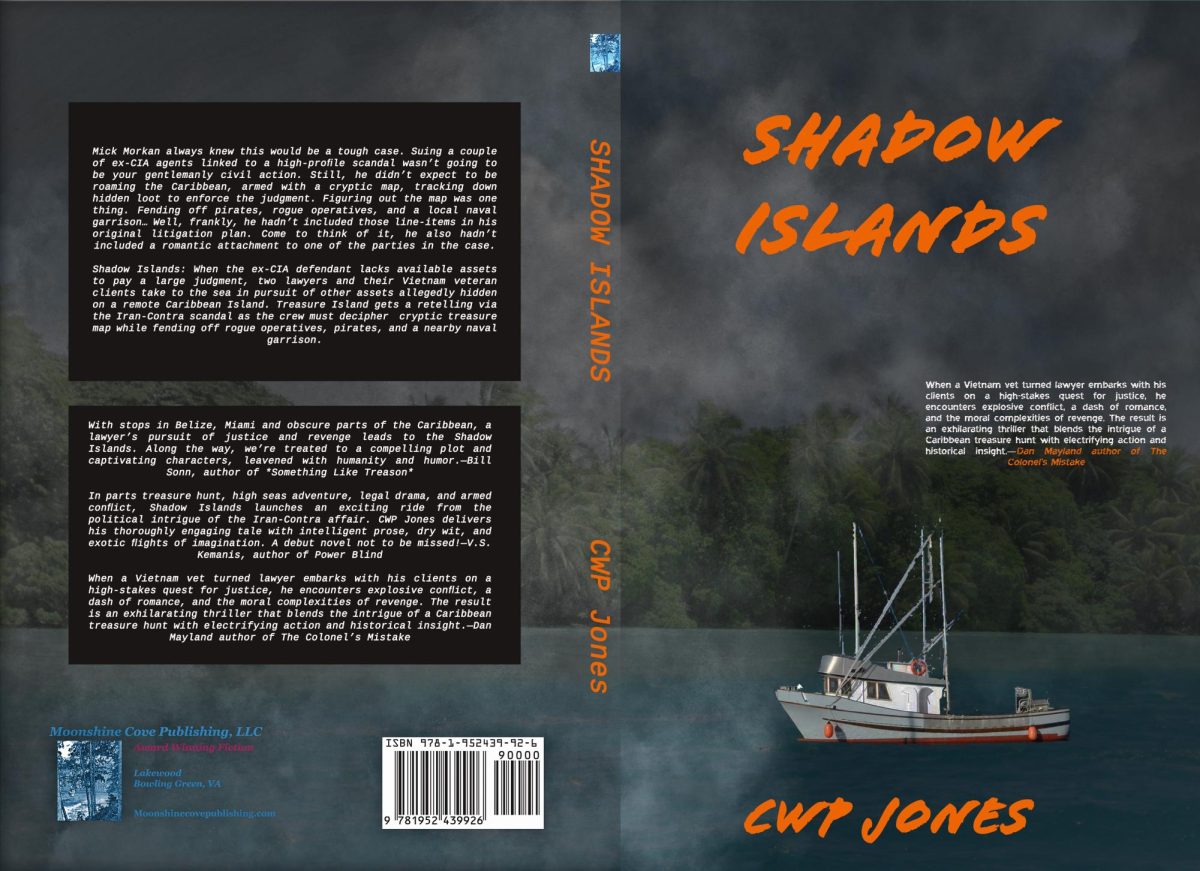

Bailey, 38, of Ossining, graduated from Peekskill’s drug court on January 17 in a ceremony where his criminal records were dismissed and sealed. He completed the drug court requirements in seven months and became the 13th graduate of the program.

The PCDTC mission is rehabilitation, not punishment. It restarted in 2019 after a seven year hiatus between 2004 to 2011 due to budget cuts. The court saw an increase in drug overdoses in the ensuing six years and a $600,000 grant from the federal government led to the re-establishment of the drug treatment court in 2019. The Northern Westchester branch office of the Westchester County District Attorney’s Office refers potential candidates from 14 jurisdictions, from North Salem to Ossining, to the PCDTC where Peekskill Judge Reginald Johnson presides.

While drug court may be held in a judicial setting, it more closely resembles group therapy where a team of people, consisting of lawyers, peer counselors, and family members, are closely involved in the lives of participants. And to preside over Peekskill’s drug court, Johnson had to participate in a training from the Judges National Drug Court.

Participation in the drug rehabilitation program is voluntary; it’s considered a legal intervention that replaces jail. A person is assessed at their arraignment by the drug court coordinator to determine eligibility for drug court.

In the 12 years of its existence, the program has seen 25 participants with half of them graduating and having their records sealed.

According to the national Office of Drug Drug court programs have a tangible effect on criminal recidivism. A study funded by the Department of Justice examined re‐arrest rates for drug court graduates and found that nationally, 84 percent of drug court graduates have not been re‐arrested and charged with a serious crime in the first year after

graduation, and 72.5 percent have no arrests at the two‐year mark.

Additionally, an analysis of drug court cost‐effectiveness conducted by The Urban Institute found that drug courts provided $2.21 in benefits to the criminal justice system for every $1 invested.

The program is a “blueprint for life”

Speaking at his graduation ceremony on a Wednesday in January, Bailey said he was motivated to change because of his parents and his 12-year-old daughter. “I owe it to my parents to be the best son they deserve and I owe it to my daughter to be the best father.” He explained how the drug court program involved more than showing up every week. “I was given the tools here to work on me and I was given the blueprint to use for the rest of my life. This taught me how to have relationships with people. There’s nothing like having a purpose.”

He spoke of the support he received from the people associated with drug court, from the program coordinator Aarin Thomas, to the treatment counselors, and the program evaluator Julie Raines. Westchester Assistant District Attorney Steven Ronco, who comes to all the drug court graduations, told Bailey that, “You gave me nothing to do.” It was Ronco who made the recommendations to Judge Johnson that the felony convictions be dismissed and sealed.

-

Brian Bailey with his mother Mary and his dad in the background.

-

The scene in the courtroom as Brian Bailey is given his certification of completion from Judge Johnson. In the foreground are representatives from the Westchester County District Attorney’s office and lawyers specifically designated as drug court attorneys.

Bailey’s mother and father traveled from Virginia to be present for the graduation and his dad spoke movingly about the growth he saw in his son.

He wasn’t the only one addressing Bailey. In presenting a certificate to Bailey, Judge Johnson described what he saw in Bailey throughout his time in the court. “The name Brian comes from Irish and means brave, mighty power, high and noble. The name is a sign of strength and virtue. It means you will help inspire and be a person of high character. You have a name that is a symbol of strength and virtue.“

Addressing Bailey, Johnson told him he has debts to pay to the people who loved him in his lowest moments. “You have your whole life ahead of you. Make the best of it.” And quoting Robert Louis Stevenson, Judge Johnson told him to, “Focus on the seeds you plant, not on the harvest. Plant seeds of joy, commitment and success. I saw and sought the best in you.”

Johnson told Bailey’s parents that he didn’t meet their son under the best of terms, but that Bailey has earned the certificate of achievement and that he exemplifies what the drug court program is about.

A peer mediator from the Lexington Recovery Center who supported Bailey spoke of how one of the most difficult parts of her job is watching people self-destruct but watching people re-construct is a whole different experience. “You came in here uncertain and unsure and you mostly learned about yourself. This requires strength,” said Anita Bonner.

“I came in here with motivation, this was going to change my life,” related Bailey.